Werner Herzog : « Il y avait en moi quelque chose de sombre. »

"I belong to a generation that holds a rather particular role in history. Men and women before me experienced profound upheavals, like those brought about by the discovery of America for Europeans or the transition from craftsmanship to the industrial age; but each time, it was a single, significant transformation. I, however, saw—despite not being from a peasant background—how meadows were mowed by hand with scythes, how hay was turned, then loaded with long pitchforks onto horse-drawn carts, before being stored in the hayloft. Farmhands toiled like serfs from the distant days of medieval feudalism. Until I discovered a mechanical hay rake, still pulled by a horse, but equipped with two parallel rotating forks that lifted the hay; then my first tractor, then, astonished, my first milking machine. This was the transition to industrial agriculture. But much later still, I experienced agriculture as practiced in the American Midwest, where armadas of powerful combine harvesters advance across immense fields that stretch to the horizon. No one disturbs these machines, even if they were still guided by humans. They were, however, already digitally connected, with a myriad of computer screens in each cabin and GPS-controlled trajectory management ensuring mathematically perfect lines. Had the steering been entrusted to a driver, it would inevitably have resulted in winding, random lines, forcing the entire convoy into improbable turns. As for the seeds, they were genetically modified. And not so long ago, I observed the beginnings of robotized agriculture, with no human presence at all. Robots distribute seeds in greenhouses, water them, regulate light and temperature, harvest, and then package the production into suitable containers, ready to be picked up by supermarkets.

I also experienced the enormous changes in the world of communication from an archaic time. I remember the municipal employee in Wüstenrot, in Swabia—just a few hours' drive from Munich and Sachrang—where my brother and I spent a year living with our father. Back then, there was a town crier. It seems to me that there is no longer a word for this function in German; in English, the term "town crier" is still used. I can still see him, walking the streets of the town as he climbed toward Raitelberg, ringing a bell to draw attention. He would stop every four houses and shout: “Notice, notice to the population!” to announce measures and deadlines issued by the administrative authorities. Since early childhood, I had known radio and newspapers, though we did not always have electricity; but I had never seen a film, and I had no idea what a cinema was. I was unaware of its existence until the day a man arrived in Sachrang with a mobile projector and set it up in the school’s only classroom to show two films that, in truth, did not impress me at all. There was no public telephone, so I made my first phone call at the age of seventeen. Televisions only became widespread in the 1960s, and it was in Munich, in the family of the janitor who lived on the floor above us, that we saw our first televised news report or football match. I experienced the advent of the digital age, of the internet, and of the transmission of content created not by humans but by algorithms. I have received emails written by robots. Social networks are profoundly altering the ways we communicate, though I do not use them myself. Video games, surveillance, artificial intelligence—history has never known such radical changes, and I find it hard to imagine that future generations will experience anything comparable within a single lifetime.

I experienced the advent of the digital age, of the internet, and of the transmission of content created not by humans but by algorithms. I have received emails written by robots. Social networks are profoundly altering the ways we communicate, though I do not use them myself.

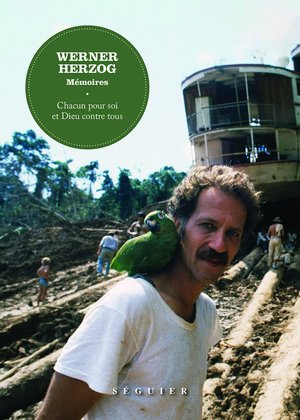

Werner Herzog

Living conditions during our childhood were archaic. We did not have running water; we had to go outside to the fountain to fill a bucket, and in winter, it often froze. The latrines, with a hole cut into a wooden plank, were attached to the house. But the wooden panels of this hut were not well joined, so gusts of snow would sometimes blow inside in winter. In such cases, my mother would place a bucket in the hallway for us to use. But in extreme cold, its contents would freeze into a solid block. Only the kitchen benefitted from the warmth of a small wood stove. The tiny adjoining room where my brother and I slept in bunk beds, as well as my mother’s bedroom, were unheated. We did not have mattresses. Unable to buy any, my mother made us straw pallets by filling coarse cloth sacks with dried ferns. But the stems of these plants, cut with a scythe, had sharp tips where the blade had sliced them at an angle. Once dried, these tips became as hard as sharpened pencils, pricking us and waking us whenever we moved in our sleep. Before long, the ferns would compact into hard lumps, and shaking out the pallet was pointless; it would become as hard as concrete. For my entire childhood, I never slept on a flat surface. In winter, it was sometimes so cold that we would pull the covers up over our heads, making small holes to breathe through, but the fabric would instantly freeze. Our room was so narrow that there was only space for a single chair between the beds and the wall. High up, just under the ceiling, was a shelf where apples were stored. We could smell them. In winter, they shriveled and froze, but they were still edible once thawed. [...]

Living conditions during our childhood were archaic. We did not have running water; we had to go outside to the fountain to fill a bucket, and in winter, it often froze. The latrines, with a hole cut into a wooden plank, were attached to the house.

Werner Herzog

"My brother Till and I thus grew up in a state of extreme poverty. But we were not at all aware of it, except perhaps during the two or three years after the war. We were always hungry, and my mother struggled to find enough to feed us. We ate salads made from dandelion leaves, and my mother prepared syrup using freshly picked narrowleaf plantain and fir buds. The first ingredient was more of a medicine to treat coughs and colds; the second was a substitute for sugar. Once a week, we could exchange our ration coupons for a large loaf of bread at the village bakery. My mother would mark it with notches for each coming day, but it amounted to just one slice per day per person. When hunger became too intense, my mother would allow us to take a small piece from the next day’s ration, hoping to find something else in the meantime; but often, we finished the loaf by Friday, making Saturdays and Sundays difficult. The most vivid memory I have of my mother, forever etched in my mind, is of a moment when my brother and I clung to her skirt, whining because we were hungry. With a terrible movement, she pulled away and turned abruptly, revealing a face of anger and despair that I had never seen before and would never see again. She said to us then: “You know, kids, if I could cut a piece of food from my ribs for you, I would, but I can’t.” From that moment, we learned never to complain again. Since then, I have despised whining.

Poverty was so omnipresent that it did not seem strange to us, except on rare occasions. At the village school, which consisted of a single classroom containing the first four years of primary school, many children were in extreme distress because they came from remote farms situated even higher above the valley. One of them, Louis Hautzen, was always late, as he had to work in the family barn before dawn. In winter, he would come sliding down the slope on a sled along a steep hollow path, arriving completely covered in snow from head to toe. The class had usually started long before. Without saying hello, he would drag his sled—still covered in ice—across the room and pass in front of our teacher, Fräulein Hupfhauer, always offering the same excuse: “Mademoiselle, I wiped out.” I no longer remember his face; but one day, at the beginning of summer, he kept his jacket on, which smelled strongly of the barn. When the teacher told him to take it off because of the heat, Louis pretended not to hear her. As he still refused to obey, she eventually hit his fingers with a ruler. I must clarify that our teacher was a wonderful person who, despite managing four levels in a single classroom, managed to teach us knowledge, enthusiasm, curiosity, and self-confidence. At the time, the ruler was part of the pedagogical tools, and no one objected. We did not find it unusual to be made, in case of misbehavior, to kneel on the edge of the platform or even balance on a log if the offense was serious. Still, Louis refused to take off his jacket, and all twenty-six of us, boys and girls aged six to ten, stared at him intently. He felt increasingly uneasy and, without a word, began to cry. His silent sobs still tear at my heart today. Louis finally took off his jacket, revealing a single shirt so worn and threadbare that it hung in tatters from his elbows. The teacher broke down in tears as well and handed his jacket back to him.

Yet nothing in my childhood suggested anything unusual, except perhaps in a negative sense. I was a quiet, rather secretive child, prone to anger, and, in a way, dangerous to those around me.

Werner Herzog

I only saw Fräulein Hupfhauer again recently, seventy years later, at a reunion of former classmates. She had taken a different surname after marrying but was now widowed. Nevertheless, at over ninety years old, she remained incredibly warm and inspiring. In my childhood, there was always the belief that I would not live an ordinary life—an opinion that my mother often confirmed when I reached adulthood. Yet nothing in my childhood suggested anything unusual, except perhaps in a negative sense. I was a quiet, rather secretive child, prone to anger, and, in a way, dangerous to those around me. I could spend hours brooding, trying to understand, for example, why 6 multiplied by 5 was the same as 5 multiplied by 6. And likewise, why 11 times 14 produced the same result as 14 times 11. Why? Numbers obeyed a law that remained obscure to me for a long time, until I visualized the problem by imagining a rectangle composed of six rows of five small stones placed side by side, after which, by rotating it a quarter turn, the principle suddenly became obvious. [...]

But let us return to my childhood. There was something dark within me. Though I do not remember it, I would take a stone in my hand and strike repeatedly, causing my mother much worry. I was withdrawn, silent, but there was a rage—something troubling within me. I only learned to channel my anger after a family catastrophe. I must have been thirteen or fourteen, and we were now living in Munich when I had an argument with my older brother Till. We were—and still are—bound by unbreakable brotherly ties, which did not prevent fierce fights between us, where punches were freely exchanged. This was considered natural and acceptable. But this time, the dispute—of which I vaguely remember that it concerned the feeding of our hamster—was so violent that I became enraged and wounded my brother with a knife. The first blow struck him at the carpal tunnel, as he had raised his hand to protect himself, and the second cut his thigh. The room was awash with blood. I was deeply horrified by my own behavior. I instantly understood that I had to change, and urgently, at the cost of iron discipline. The event was monstrous. I had committed the worst crime imaginable, one that could have shattered our family. A careful inspection revealed that my brother’s wounds were not as serious as we had feared, so we resolved, in a brief family council, not to take him to the hospital, for fear that it would lead to a police investigation. We bandaged the wounds and cleaned up the blood on the floor, in a state of shock. I remain deeply shaken by this event to this day. Because Till’s wounds had not been stitched as they should have, he still bears the clearly visible scars. This tragedy forced me to master myself and to rigorously discipline my emotions from then on.

There was something dark within me. Though I do not remember it, I would take a stone in my hand and strike repeatedly, causing my mother much worry. I was withdrawn, silent, but there was a rage—something troubling within me.

Werner Herzog

To this day, I continue to impose strict self-control on myself, and it is a defining trait of my personality. Yet the relationship between Till and me will forever have a raw, often humorous, and affectionate quality, incomprehensible to outsiders. A few years ago, we reunited for a family gathering on the Spanish coast, where my brother was living at the time. He invited us to a wonderful evening in a seafood restaurant, sat next to me, and threw his arm around my neck as I looked at the menu. Suddenly, I noticed smoke and felt a slight sting on my back, only to realize that he had set fire to my shirt with a lighter. I quickly took it off in front of the stunned diners, but both of us laughed heartily at this prank that no one else could understand. Someone lent me a T-shirt to finish the evening, and I treated my skin’s redness with prosecco." ◼

* Éditions Séguier, traduction de l'allemand Josie Mély

Related articles

In the calendar

Portrait de Werner Herzog

Photo © Lena Herzog