Werner Herzog: Surviving Cinema

At the end of 2008, the Centre Pompidou presented the complete body of work by Werner Herzog, beginning with his first short film, Herakles (1961). This event marked a celebratory return. The 1980s and 1990s had not been kind to the German filmmaker. While those decades yielded remarkable films, Herzog’s reputation had suffered from what many perceived as an excess of provocation. By 2008, however, he had reclaimed the position that had always been rightfully his: that of one of the greatest living filmmakers. The seeds of this comeback can be traced to 1999 with the release of My Best Fiend. In this portrait of Klaus Kinski and the tumultuous history of their collaboration—which spanned seven films, several of which have left a lasting imprint on modern cinema—Herzog realised that the cruelty of their shared past had softened into the tenderness of memory. This marked the beginning of a new phase in his career, one that continues twenty-five years later. In 2024, Werner Herzog has not retreated. He remains with us, active and admired—by those who have followed him since his early days and by those who are just now discovering his work. All is well.

In 2024, Werner Herzog has not retreated. He remains with us, active and admired—by those who have followed him since his early days and by those who are just now discovering his work.

This time, then, it is Herzog’s longevity and consistency that we celebrate. He has continued to make films at a steady pace, averaging about one per year. As always, he alternates between fiction and documentaries, with a slight preference for the latter. An accomplished writer as well, Herzog recently published his memoirs in France under the title Every Man for Himself and God Against All, echoing the subtitle of one of his most celebrated and beautiful films, Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972). He has remarked that his posthumous legacy may owe more to his writing than to his cinema. Beyond filmmaking, Herzog has acted in movies—alongside stars like Tom Cruise—directed operas, lent his voice to children’s audiobooks, exhibited in museums, and presided over juries at major festivals. Truly, all is well.

Beyond filmmaking, Herzog has acted in movies—alongside stars like Tom Cruise—directed operas, lent his voice to children’s audiobooks, exhibited in museums, and presided over juries at major festivals.

Werner Herzog turned 82 on September 5, 2024. He can no longer embody the fearless adventurer he once was—the tireless walker, agile climber, cold-defying explorer, and daredevil filmmaker who ventured into jungles and deserts. Not that his health shows any signs of decline, but his role has inevitably evolved over time. The only truly global filmmaker—having shot on all seven continents—now stands as a veteran, even a survivor. He is acutely aware of this and approaches filmmaking from this perspective. Many of those he worked with, travelled with, or would have liked to film are no longer alive. They have died not so much from old age as from exhaustion, illness, or accidents—killed in volcanic eruptions, attacked by bears, or executed in electric chairs. Herzog, on the other hand, remains, and he likely reflects on the daring life he has led with a wry smile. It is this shift, since 2008, that marks the opening of another phase: a time of remembrance.

Survivor—this term has applied to Herzog since his youth. His cinema has always wrested life from the grip of death—or, if not death, from disaster, failure, or exploits so grandiose they shatter all limits. And first, it wrested life from the Germany of the first half of the 20th century. The term ‘survivor’ holds at least two meanings: the person who has not died and the person who seeks to live a life beyond the ordinary. Both meanings have always been intertwined in Herzog’s work. Recently, however, a third dimension has emerged, enriching the first two.

The dimension of homage has always been present in Werner Herzog’s work, at least since Land of Silence and Darkness (1972), where the young filmmaker lovingly portrayed Fini Straubinger, an elderly woman who was blind and deaf. He paid tribute to Dieter Dengler, an American military pilot imprisoned in the Laotian jungle in 1966, in Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997). Likewise, he honoured Juliane Koepcke, the sole survivor of a plane crash in Peru, in Wings of Hope (2000). These homages were created with their subjects’ participation, blending factual recounting (in the past tense) with reenactments (in the present). Herzog’s approach evolved further with My Best Fiend in 1999, which altered the dynamic: Klaus Kinski had died in 1991, making distance inevitable. Six years later, Grizzly Man (2005) clarified this shift. Timothy Treadwell, the Alaskan bear enthusiast, had been killed by a bear two years earlier, and Herzog’s film relied heavily on Treadwell’s own footage. In Grizzly Man, Herzog primarily served as editor and narrator—little more. From then on, everything changed. His cinema became rooted in the past, reflecting on lives and feats now closed, and drawing on archival footage that itself belonged to history.

The only truly global filmmaker—having shot on all seven continents—now stands as a veteran, even a survivor. He is acutely aware of this and approaches filmmaking from this perspective.

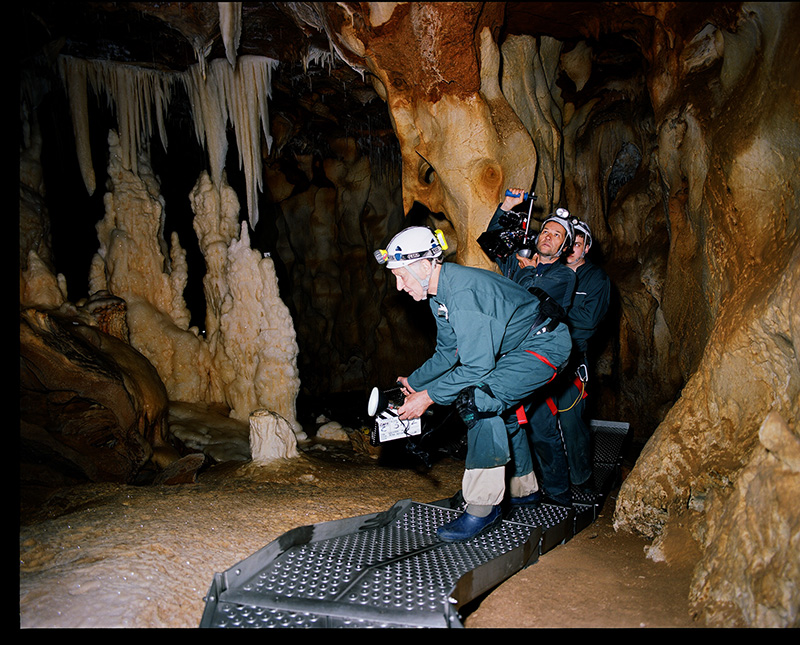

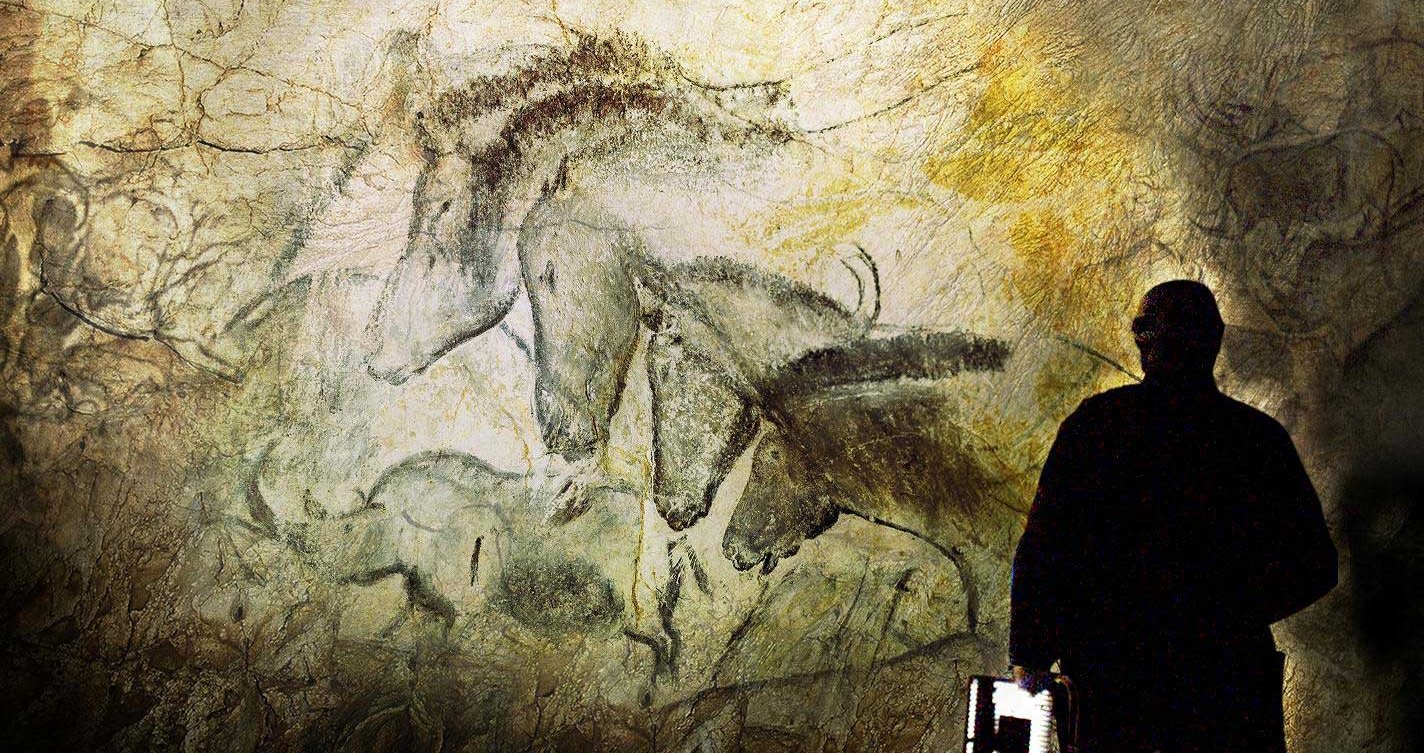

Since 2008, Herzog has made around fifteen films, with the Centre Pompidou presenting about half of them. This selection includes five documentaries, each a tribute, and two fictions that deserve attention. These films are retrospectives, revisiting people and realities now gone. They are requiems, as signalled by the subtitle of The Fire Within: Requiem for Katia and Maurice Krafft. In Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), Herzog and a minimal crew gained access to the Chauvet Cave in Ardèche to marvel at Paleolithic paintings. In Into the Abyss (2011), he met with death row inmates in Texas, exploring the existential question of how one continues to live knowing they are, in a sense, already dead. Meeting Gorbachev (2018) deviates slightly, as it honours a still-living figure—though Herzog’s interest lies in Mikhail Gorbachev’s historical impact, particularly in paving the way for German reunification. In Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin (2019), Herzog remembers the writer and traveller who was a close friend, whose work he adapted for Cobra Verde (1987), his final collaboration with Kinski, and who left Herzog his rucksack when he died in 1989. Finally, in The Fire Within (2022), Herzog compiles footage shot by Alsatian volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft, who perished in a 1991 volcanic eruption in Japan, to recount their dual scientific and cinematic journey.

Survivor—this term has applied to Herzog since his youth. His cinema has always wrested life from the grip of death—or, if not death, from disaster, failure, or exploits so grandiose they shatter all limits.

In this film, Herzog speaks explicitly about cinema—a rare occurrence for him and one worth noting. He expresses admiration for the Kraffts as filmmakers and for the astonishing power of the images inspired by their passion for volcanoes. Yet Herzog has never been an aesthete nor a self-proclaimed cinephile. In The Fire Within, he uses the Kraffts as a proxy to speak, indirectly, about himself as a filmmaker. Though typically reserved and averse to self-reflection, it is clear that each requiem allows him to refine a kind of indirect self-portrait. What is The Fire Within ultimately about? It touches on the core of Herzog’s lifelong concerns: the delicate balance between capturing images and taking risks, and the line that must never be crossed. He argues that the Kraffts’ increasing focus on filmmaking at the expense of science led them to neglect danger and ultimately cross that line. In Herzog’s view, it was not the erupting volcano that killed them, but their artistic ambition.

Herzog’s unique greatness lies in a paradox: his filmmaking brilliance is inseparable from a certain reluctance, even a disinterest, in cinema as an art form.

Why is this significant? What does it reveal about the Werner Herzog of the 2010s and 2020s? For years, Herzog wrestled with this very line—the idea that cinema must know when to resist itself, when to lay down the camera. His propensity to take extreme risks, and his occasional inability to resist the allure of danger, earned him a reputation for madness. Brilliant, but mad. Too mad, some said, to be truly brilliant. That time has passed. Today, Herzog presents himself as a sage. He has lived, dared, and filmed enough to feel capable of offering wisdom—even if in hindsight. It could seem ridiculous, but it is deeply moving. In several recent films, Herzog asserts his conviction that he may be the only sane filmmaker in the world—a madness of another kind, perhaps, but a beautiful one that underscores where Herzog now stands: in a retrospective phase, both admiring and critical of past feats, including his own. This retrospective stance extends to his cinema, which increasingly draws on the images of others, needing less and less to venture out himself. Herzog’s unique greatness lies in a paradox: his filmmaking brilliance is inseparable from a certain reluctance, even a disinterest, in cinema as an art form. This was true in the past and is even more so today. It is why the beauty of his documentaries has never been hindered by their often conventional form, nor the charm of his voiceovers diminished by their perfectly monotonous tone.

Today, Herzog presents himself as a sage. He has lived, dared, and filmed enough to feel capable of offering wisdom.

Finally—a brief postscript on the two fictions in the programme: Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009), with Nicolas Cage reprising a role played by Harvey Keitel in Abel Ferrara’s 1993 film, and My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done (2009), starring Michael Shannon, Chloë Sevigny and Willem Dafoe. These two films stand apart in a filmography already known for its remarkable diversity. They are singular works, unlike anything else in any filmography. Herzog has often been accused of not knowing how to tell stories—a claim not entirely unfounded. His documentaries are indeed considered stronger than his fiction films. Yet Bad Lieutenant and My Son, My Son prove that Herzog can also be an exceptional director of crime dramas. In particular, Bad Lieutenant showcases the “ecstatic truth” Herzog often speaks of, finding one of its most unforgettable expressions in Nicolas Cage’s performance. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), Werner Herzog

© Metropolitan Films