Masterpieces

Constantin Brancusi

« La Muse endormie », 1910

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

In its mass and the polish that renders it almost translucent, Constantin Brancusi's (1876-1957) Phoque II presents a tension between equilibrium and disequilibrium, inertia and energy. Animal form, most commonly raised to verticality in Brancusi, more occasionally appears between the vertical and the horizontal: integral, tensed, captured in its movement.

There exist three versions of the Phoque: Phoque II in blue marble and the plaster made from it differ from Phoque of white marble (1936) in their large scale: the dynamism of the form finds itself opposed, as it were, by the greater mass of material between the belly and the flexed back. The lines that define the body develop a play of contradictory curves. It is these that give Phoque its equilibrium: the plaster seems as if to be leaping forward from its circular plinth; the marble can revolve with its base, mounted on ball bearings.

Vassily Kandinsky

« Mit dem schwarzen Bogen (Avec l'Arc noir) », 1912

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

A thick black arch stretches over three colour blocks, holding them at a distance as they are apparently on the point of collision.

Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) has invented a richly nuanced world of moving shapes and colours. In quivering touches, lines dissociate from colour, creating as much discord as alliance. Adopting composer Arnold Schönberg’s dissonance principle, this research led him to abstract pictorial language. He distances himself from appearances, too fleeting, to reach the inner world where souls vibrate. For him, painting needs to engender strong, captivating sensations, as when listening to a concert.

Marcel Duchamp

« Fontaine », 1917/1964

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) bought a urinal, turned it over, signed it "Richard Mutt" and dubbed it the Fontaine and presented it as a work of art.

He then sent it to a New York gallery, where it was rejected. The jury of artists was not yet prepared to admit this provocative artwork. Duchamp called it "ready-made": elevating an industrial object to "work of art" status, simply because the artist chose it.

With this simple act, Duchamp conferred a new viewpoint for the object as well as the very artistic sphere. What is the artist’s role? How do you define "work of art" in the age of film, photography, and industry? Does it still have to be beautiful? Unique? Purely intuitive? Hand-made? Non-reproducible? Raising such questions did not always lead to answers, but did completely shake up 20th-century art.

Robert Delaunay

« Manège de cochons », 1922

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

A pair of black-stockinged legs, swept up in a riot of colours, projects the noisy atmosphere of a Roaring Twenties funfair.

Myriad coloured discs, Robert Delaunay's (1885-1941) favourite motif, seem to rise from a top hat. Their "tumultuous orchestration" draws onlookers into a merry-go-round’s frantically swirling movement and music. The modern, brightly-lit, colourful city with its new advertising hoardings and popular, entertaining sports are a source of new sensations for the painter. In the foreground, Robert and Sonia Delaunay’s friend Tristan Tzara, the dada poet, signifies the close ties between the painter couple and contemporary poetry.

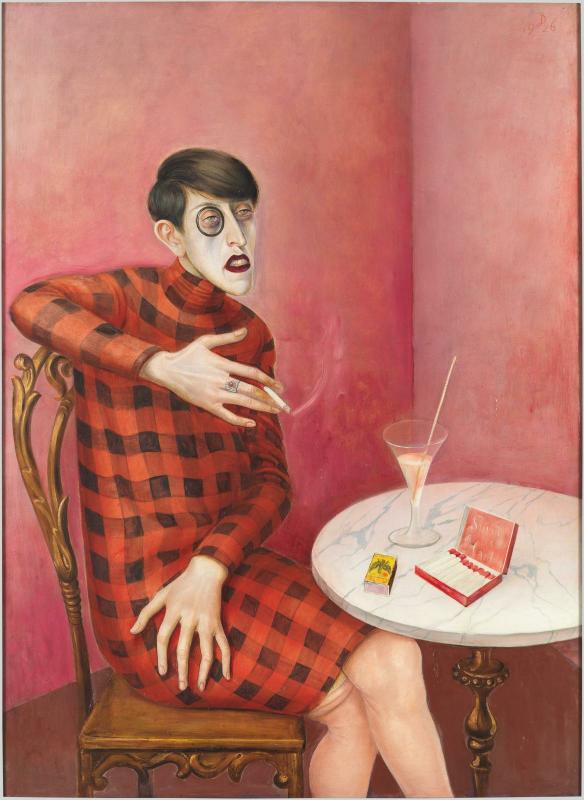

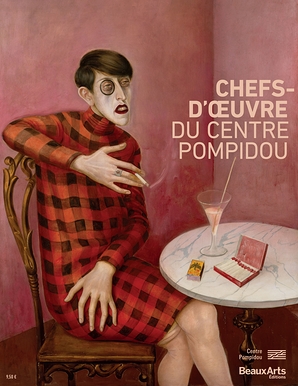

Otto Dix

« Bildnis der Journalistin Sylvia von Harden (Portrait de la journaliste Sylvia von Harden) », 1926

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Who is this woman who dares to appear in public alone, cigarette in hand, at a table of the Romanische Café, a haunt of the Berlin literary and art worlds? Sylvia von Harden was a journalist in Berlin in the 1920s. Her ostensibly nonchalant stance is a statement of her emancipated intellectual role. Otto Dix (1891-1969) undermines her arrogance with the detail of a loose stocking and her rather awkward pose. Her red-check dress contrast with the pink environment, typically Art Nouveau. The cold, satirical realism typifies the New Objectivity movement to which the painter belonged. Inspired by early 16th-century German masters (Cranach, Holbein), he embraced the tempera on wood panel technique as well as the choice to exhibit the ugliness of the humankind.

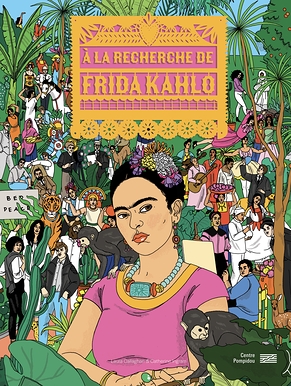

Frida Kahlo

« The Frame », 1938

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Born in Mexico in 1907, Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) sustained a terrible accident at the age of 18, and started painting while lying on a hospital bed. This was the first of a long series of self-portraits. In 1928, she met muralist Diego Rivera, and married him the following year. Her tumultuous life with him, her physical and mental suffering then became the main themes of her work.

This self-portrait was painted on a fine aluminium sheet, overlaid with glass plate painted by Mexican artisans on the underside. Frida Kahlo’s face thus stares out from a frame typically used for a mirror, photo-portrait or holy icon. The artist’s face shines through luxuriant décor. Its gaudy colours and ornamentation are reminiscent of accessories and Pre-Columbian objects that feature heavily throughout Frida Kahlo’s work.

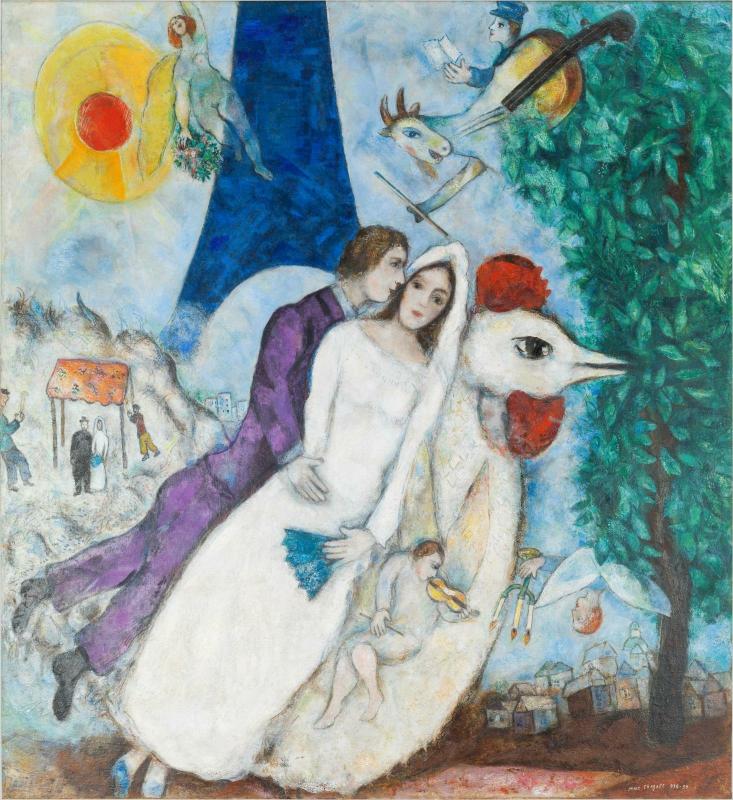

Marc Chagall

« Les mariés de la Tour Eiffel », 1938-1939

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

A large white cockerel whisks the painter and his wife in full bridal finery into an indeterminate décor mingling Parisian and Russian elements.

After their first trip to Paris from 1911 to 1914 and participation in the Bolshevik revolution, Marc Chagall (1887-1985) moved to Paris with his wife Bella. The newly-weds are surrounded by a hotchpotch of souvenirs from Russia, music, Parisian life and animals. To the right, the couple’s native Jewish quarter risks catching fire from the flames of a chandelier snatched by an upside-down angel. Seeing signs of imminent war in 1938-1939, Chagall painted a fragile hapiness.

Henri Matisse

« La Blouse roumaine », avril 1940

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

The ornamental embroideries of the blouse are actually the main topic here, as the painter showed great interest in all types of fabrics.

Whether in embroidery, fabric or rugs, Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was moved by the graphic beauty of motifs in craftsmanship and their colourful rhythm. On the model, the Romanian blouse acts as a high-dose stimulant for the painter. He conveys his exaltation, smoothing out details, streamlining lines and creating colour blocks, as the stylisation of the oak leaves central ornaments suggests it. The blouse billows out, becoming pictorial space as much as metaphor.

11 photographs show the various stages of creation for this portrait, gradually erasing the young girl to better emphasise the embroidered blouse.

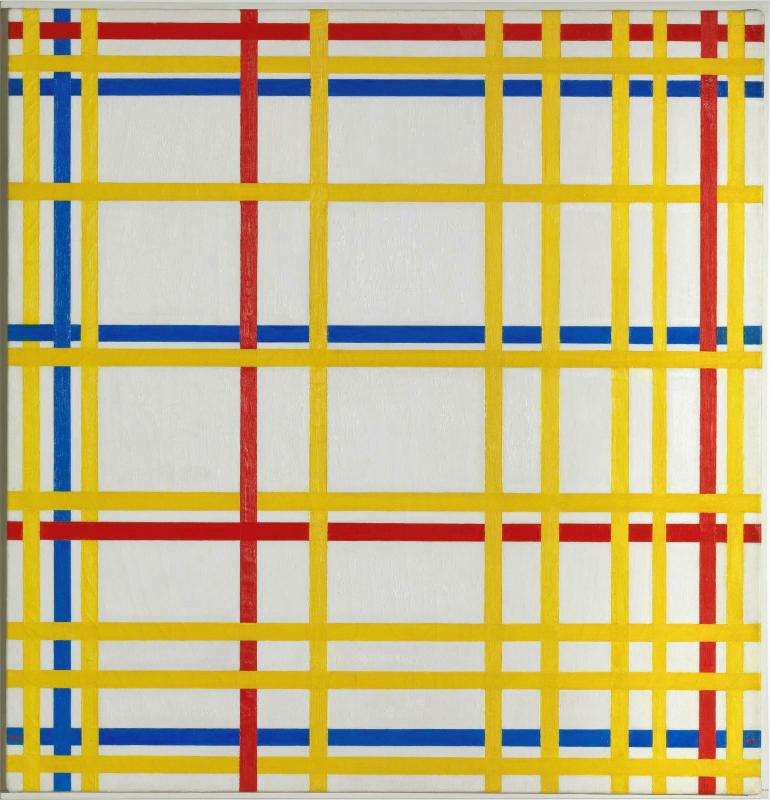

Piet Mondrian

« New York City », 1942

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

The orthogonal structure translates the effervescence of New York.

In New York, architectural gigantism, perpendicular urbanism and frantic traffic have a great impact on exiled European artists, just like PIet Mondrian (1872-1944), who arrives there in1940. This work is typical of Mondrian’s last research, after his neo-plastic period and black grids. His vertical and horizontal lines vibrate with colour, creating a luminous optical dynamic and an impression of movement. The dense criss-crossing over the entire surface magnifies the USA’s "new energy", boosted by the discovery of the frantic boogie-woogie beat.

À lire aussi dans notre Magazine

Fernand Léger

« Les Loisirs-Hommage à Louis David », 1948-1949

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Here, Fernand Léger (1881-1955) glorifies popular leisure activities (familial biking, picnic), and alongside them, the paid vacations granted in 1936 under the Front Populaire.

On his return from New York in 1945, the painter declared that he would come back to "a direct art, comprehensible to everyone". As a historical painting, Les Loisirs also offers an apology to the sober and hieratic style of the painter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) – the women’s posture in the foreground is a reference to the painting La Mort de Marat (1793). The stylised figures dressed, for some of them, in the American fashion seem to look straight at the spectator. They represent the heroes of a history in the process of becoming one.

Ben

« Le magasin de Ben », 1958-1973

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

In 1958, Benjamin Vautier (aka Ben, 1935-2024) set up a shop at 32, rue Tondutti de l'Escarène in Nice. In affinity with Marcel Duchamp’s ideas, Ben’s work is based on the premise that "everything is art".

Licensed to deal in second hand goods, he bought and sold second-hand records, cameras etc. Known as "Laboratoire 32", then "Galerie Ben doute de tout", it eventually became the "Centre d'art total", a place for publishing, meet-ups and debate, especially with artists from the newly-formed Nice school. Ben’s shop juxtaposed myriad elements, turning it into an ever-evolving sculpture that he called "N'importe quoi" ("Just anything"). It was taken down in 1972 and purchased by the Centre Pompidou. The artist gradually rearranged it to give it a life of its own in this new context.

À lire aussi dans notre Magazine

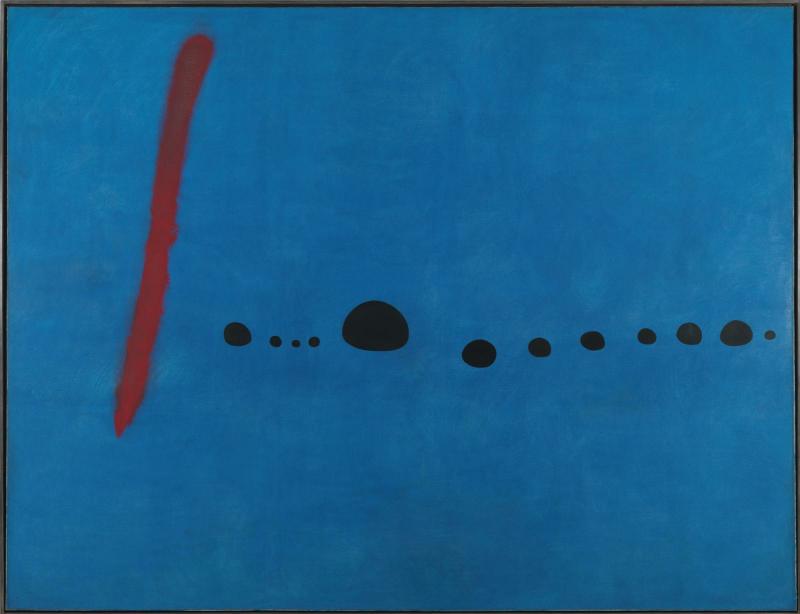

Joan Miró

« Triptyque Bleu I, Bleu II, Bleu III », 1961

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

The Catalan artist was part of the Surrealist movement in 1924. His painting was inspired by the free, dreamlike imagery in the poetry of Apollinaire, Eluard and many others.

Joan Miró (1893-1983) designed his 3-part Blue series in his new studio - built in Palma de Mallorca by his friend José Lluis Sert in 1956 - then painted them between December 1960 and March 1961. They were the product of a long maturation process, in which the great Catalan artist returned to his meditations on space and the act of painting. He explained that these three masterpieces were the result of a "very great internal tension in order to arrive at a desired sobriety".

Yves Klein

« SE 71, L'Arbre, grande éponge bleue », 1962

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

For this Arbre, Yves Klein (1928-1962) used a kind of blue that he invented, and that has been referred to as "Bleu Klein" since then. The sponge becomes the material for his work after being the painter’s tool.

From 1954 until his early death in 1962, Klein produced a body of work that reflects on the immaterial and the imbrication of art with day-to-day life. In 1960, he joined the New Realists movement who "considered the world to be a picture" from which they "appropriated fragments" (P. Restany). This "tree", blending the remains of impregnation and natural processes, is the most monumental sculpture that the artist has made, one of the artist’s last works.

À lire aussi dans notre Magazine

Martial Raysse

« Made in Japan - La grande odalisque », 1964

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Martial Raysse (born in 1936) moved to Los Angeles in 1963. His pictural language is akin to pop art, especially that of Roy Lichtenstein.

With this "Made in Japan" series, Raysse summons up icons from art history for pastiche purposes: Cranach the Elder, Tintoret and of course Ingres, whose work is perfectly illustrated here. As ever in the spirit of appropriation and repurposing peculiar to pop art and new realism, this picture was achieved using an enlarged snapshot. The artist has eliminated all but its contours, perpetuating an apology for feminine charm and sensuality in a language turning expressionist, even kitsch: "Beauty is bad taste. [...] Bad taste is the dream of an over-desired beauty."

Jean Dubuffet

« Le jardin d'hiver », 1968-1970

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

The Winter Garden started out as a vinyl-painted polystyrene mock-up, which led to another in epoxy painted with polyurethane (both dated 16 August1968). It was then enlarged from June 1969 to August 1970.

In this cavernish "garden", where nothing is natural, the decor is reduced to mere black lines on a white backdrop. However, the project of Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985) is complex: the ground and walls are uneven and dented, with the black marks apparently enhancing or contradicting the bumps. Looking beyond optical edification, this contemplative architecture challenges the onlooker’s entire perception.

Agam

« Layout of the antechamber to the private apartments at the Elysée for president Georges Pompidou », 1972-1974

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Yaacov Agam (born in 1928) produced this layout for the Elysée palace, commissioned by the French Head of State in 1971. It is a prime example of "kinetic" pictural space scaled up to living-room size, including the walls, ceilings, floor and doors. The lounge brings the artist’s principles of "polymorphic imagery" to interior architecture, using bevelled, coloured elements and presenting abstract compositions that change according to the onlooker’s viewing angle.

Overseen by Mobilier National (a government agency managing State-owned furniture), production started in 1972. Georges Pompidou died in April 1974, before completion of the Lounge. It was finished that year, and rounded off with a rug made by the Manufacture Nationale des Gobelins and a mobile sculpture in stainless steel, also designed by Agam.

Joseph Beuys

« Plight », 1985

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Created in autumn 1985 in London, Plight neatly epitomises Joseph Beuys' (1921-1986) art.

Visitors enter a claustrophobic space comprising two rooms with walls lined with rolls of felt. The entrance is designed to make visitors stoop, as a rite of passage leading to a thermal and acoustic experience: the felt absorbs both heat and sound. Onlookers are then confronted with double silence: that of their environs and of a grand piano in the first room with a closed lid - a picture featuring empty staves to underline this musical mutism.

The entire set-up invites musings on freedom, fostering awareness of a potential creator of all individuals.

Louise Bourgeois

« Precious Liquids », 1992

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Inside the water tower for a New York building hangs a network of glass vials and stills. In this sombre décor, clothing and other items record the fleeting traces of characters.

A man’s coat (the father), a young girl’s embroidered blouse, teat-shaped and phallic sculptures all set the scene as sketched by Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) in her notes: "The little girl seeking refuge in the greatcoat represents a child who has been subjected to strong emotions and proved capable, as she matures, of feeling pity for the Great Extravagant attention-seeker."

Looking beyond the installation’s narrative aspect, Louise Bourgeois gives her take on the virtues of art, with the proclamation that "Art is a guaranty of sanity" on the metal band circling the water tower.

Annette Messager

« Les Piques », 1992-1993

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

With Les Piques, Messager forcefully insists on the artist’s conscience, indispensable "witness to its time".

Annette Messager’s childlike yet nightmarish world serves as a vehicle for reflection on women’s identity and the place of the artist in society. She has repainted images of contemporary horrors, which are flanked by impaled creatures not altogether human, echoing France’s revolutionary Reign of Terror. The artist explores the dark side of humanity, indifferently mixing together victims and executioners, fiction and reality, individual body and great history.

Giuseppe Penone

« Respirare l'ombra », 1999-2000

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Guiseppe Penone’s sculptures have always demonstrated a sensitive relationship to nature, especially trees.

Respirare l'ombra is an environmental piece, calling on one’s sense of sight and smell. Lined with myriad laurel leaves secured beneath wire mesh, the room is heavy with their persistent scent, imbued with a green hue which fades over time. At the centre stand two hirsute bronze sculptures. They appear to be swept by a draught that lifts their foliage.

Penone (born in 1947) invites the visitor to meditate on the transience of things.

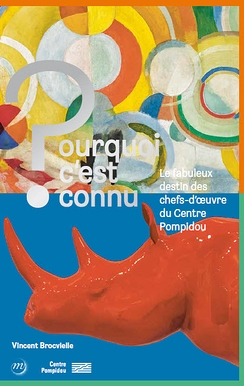

Xavier Veilhan

« Le Rhinocéros », 1999-2000

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Xavier Veilhan’s work seeks effect deliberately, playing with the onlooker’s perceptions and sensations. His subjects are drawn from everyday family culture (animals, objects and vehicles), making up a world of imagery at once generic yet strange given their smoothed, standardised aspect.

Here, the artist (born in 1963) seems to have deliberately overturned an advertising cliché for cars, whereby the make is associated with a fast animal - the Ferrari horse, the Peugeot lion etc. This paradoxic sculpture teams the animal and its weight to cars, suggested by the red enamel bodywork, and its speed. The slight oversizing and the excessively smooth, shiny surface knock perception out of kilter despite the project’s apparent simplicity.

Anselm Kiefer

« Für Velimir Chlebnikow : Schicksale der Völker (Pour Velimir Khlebnikov : destins des peuples) », 2013-2018

Zoom into the artwork in high definition

and explore all details

Time, history, war and the human condition underpin the thinking of Anselm Kiefer (born in 1945), tapping into poetry, philosophy, mythology and alchemy.

Anselm Kiefer has based this work on the parascientific theory of Russian poet Velimir Khlebnikov (1885-1922) who claimed that naval battles were cyclic events occurring every 317 years. Rusty sculptures of submarines have been assembled in two monumental displays. Onlookers can contemplate their own reflection, becoming characters in the drama staged by the artist.