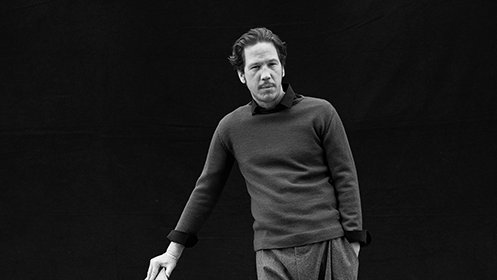

Sébastien Kheroufi, Dramaturgy in the Flesh

Sébastien Kheroufi feels at home backstage at the Centre Pompidou. Brimming with energy and ready to tackle a busy day, he begins his morning ritual: downing his essential coffee, instant and tasteless, dispensed mechanically by the Level-1 vending machine. Familiar with everyone, he greets them with kind words or hearty hugs, knowing nearly every name in the maze-like basement. The affable, bearded thirty-something—wearing a plaid bucket hat, leather jacket and hoodie—is a regular at the venue. In spring 2023, he presented a performance Insulting the Audience, as part of the “Moviment” programme. By winter 2024, his acclaimed adaptation of Handke’s Across the Villages (1981) was already playing to packed houses, blending professional and non-professional actors. And yet… nothing initially destined him for directing.

Sébastien Kheroufi’s double heritage—French through his mother and Algerian through his father—as well as the love of his parents, were for a long time his only assets.

He spent his childhood and teenage years between a housing project in Meudon-la-Forêt, in the Hauts-de-Seine, and Sonacotra hostels, notably in Belleville, where, at the age of 17, he discovered his father’s lifeless body. “Rage was a driving force. The rage of seeing your father die in a hostel. That idea got into my head very quickly,” he confides. One of his brothers left the neighbourhood, the other ended up in prison, while petty crime, racial profiling and the inaction—or incompetence—of public authorities were a constant presence around him. “Nothing has really changed since Malik Oussekine’s death, killed by French police in 1986. He was from the same neighborhood,” Kheroufi laments. Rage became his inheritance, along with an urgent need to breathe fresh air.

Rage was a driving force. The rage of seeing your father die in a hostel. That idea got into my head very quickly.

Sébastien Kheroufi

Armed only with a vocational diploma in mechanics, he crossed the Channel to join an acquaintance from a nearby neighbourhood in London. British poverty was no better than its French counterpart: the humiliations were the same, the struggles identical. Bus driver, mechanic, window salesman in the City of Light, dishwasher, and cleaner in world-city hotels. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do. The whole time, I felt humiliated.” Then one day, Kheroufi pushed open the door of a movie theatre … to clean it. “It was a small neighbourhood cinema, far from the blockbusters I was used to. To learn English, I went to screenings for the hearing-impaired. Since I didn’t understand anything at first, I focused on the light, the shots, the acting. I discovered the technique, the poetics of cinema, the art of directing.”

One of our brothers abandoned us, and here I am, still alone with my mother in the housing project; dramaturgy is in my flesh. You don’t need much education to understand what abandonment feels like.

Sébastien Kheroufi

When he returned to Meudon, Sébastien Kheroufi knew what he wanted to do. Because acting classes “cost the same as a welfare check”, he enrolled in the local conservatoire, connecting with people who shared his background and concerns, leaving behind his initial apprehensions. “I started with joy, by having fun, by finding familiar spaces.”

They explored their origins while performing works by Bernard-Marie Koltès, the French playwright, and Peter Handke, the Austrian writer and 2019 Nobel laureate, whose play Across the Villages tells the story of Gregor, a writer returning to his hometown. “One of our brothers abandoned us, and here I am, still alone with my mother in the housing project; dramaturgy is in my flesh. You don’t need much education to understand what abandonment feels like.”

My first book was by Handke. That’s when I thought theatre was incredible.

Sébastien Kheroufi

By chance, Across the Villages was also the text for the entrance exam at the École Supérieure d’Art Dramatique in Paris (Ésad). “It was the first book I read cover to cover,” Kheroufi says with infectious enthusiasm. “My first book was by Handke. That’s when I thought theatre was incredible.”

Because humility prevents him from attributing his acceptance at Ésad solely to his talent and determination, Kheroufi wonders if it was because he was the “Arab guy of the class”, “the one from the projects”. Over time, he started to feel like Gregor from Across the Villages: “As time went on, when I returned to the housing project, in the eyes of others I appeared a little more artistic. I was the Parisian coming back from the big city.” For him, those three years at Ésad—filled with encounters and discoveries—represented the joy of doing what he truly loved, defying his family’s expectations: “I grew up with the question of a permanent job contract. A permanent job is for paying the rent of your low-income housing. Happiness? We’ll see about that later. First, a roof over your head, then we’ll see.” Yet, hanging over him like the sword of Damocles was the pressure to succeed at all costs—to avoid going back to square one and, above all, to avoid embodying failure or unyielding determinism: “That’s my obsession: Who do we represent? How do we represent?”

You can’t assume people can’t understand literature. You just need to give them the right tools to engage with a work. That’s it.

Sébastien Kheroufi

Convinced that poetry and theatre are also political tools, and encouraged by Wajdi Mouawad, director of the Théâtre National de la Colline, to take on Across the Villages head-on, Kheroufi joined the Ateliers Médicis. The play, staged at Théâtre l’Azimut d’Antony, was preceded by workshops with school classes: “I arrived in Châtenay-Malabry, in the Butte-Rouge neighbourhood, right across from the housing project where I grew up.” This gave Kheroufi the opportunity to demystify the creative process, making theatre accessible to everyone, and to repair the exclusion he himself had experienced. “You can’t assume people can’t understand literature. You just need to give them the right tools to engage with a work. That’s it. Meeting young people and talking with them before a performance demystifies it. You give them keys. Looking at a Matisse is accessible, but what a journey to get there. The first time I walked into an exhibition, I was completely lost. Art is incredibly intimidating.”

My grandmother died exactly one year to the day after my father. She used to tell everyone, ‘He left on his own two feet and came back in a coffin. What happened in France?

Sébastien Kheroufi

Sébastien Kheroufi also works in Emmaus shelters with women who have fled violence in their countries. “Through art, I’m going back to all the places I grew up,” he explains. “Young people from the projects don’t need Across the Villages explained to them a thousand times. It’s the same for these women; better than anyone, they understand Antigone.”

This Greek tragedy by Sophocles was staged by Kheroufi in spring 2023 at Ariane Mnouchkine’s Théâtre du Soleil. If literature resides in the gut, there is no doubt now that theatre is etched into the flesh. For Kheroufi, Antigone offered an opportunity to address the often misunderstood theme of exile: “My grandmother died exactly one year to the day after my father. She used to tell everyone, ‘He left on his own two feet and came back in a coffin. What happened in France?’” Now, this tireless director is preparing to tackle the theme of children in the final piece of a triptych: “And us, the children—what do we do with all these wounds?”

For Kheroufi, theatre cannot be confined to the stage. A case in point: during performances of Across the Villages at the Centre Pompidou in February 2023, the costumes were accidentally donated to Emmaus. At Les Halles, passersby could be seen wearing clothes meant for the stage. “I owe so much to these organisations,” the director says philosophically. “It was winter; our costumes were more useful to them than to us.” ■

Related articles

In the calendar

Le metteur en scène Sébastien Kheroufi dans les coulisses de la Grande salle du Centre Pompidou

© Pierre Malherbet, 2024