Restoring the Past through Militant Filmmaker Sarah Maldoror’s Films

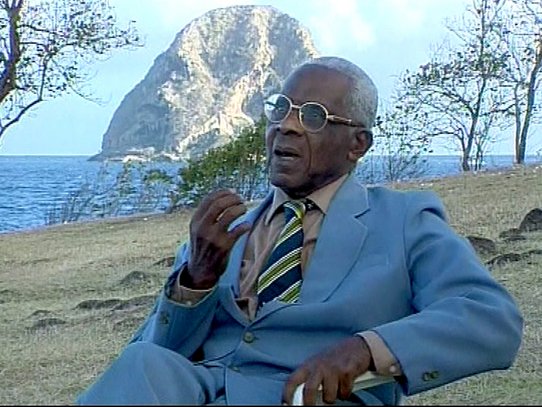

On the screen of a projection room at L’Image Retrouvée—the French branch of one of the world’s largest film laboratories, based in Bologna, Italy—the intellectual Édouard Glissant appears, visibly aged, stirring strong emotion. As he walks through the bowels of the Fort de Joux in the Jura mountains, he reflects on the fate of Toussaint Louverture—the freed slave, general of the Empire, and Haitian revolutionary—who died in this bleak prison, far from his birthplace in Cap-Haïtien. These images are taken from Regards de mémoire (2003), a film by Sarah Maldoror, and shown in a small private screening room tucked away atop a building on Place de Clichy, Paris.

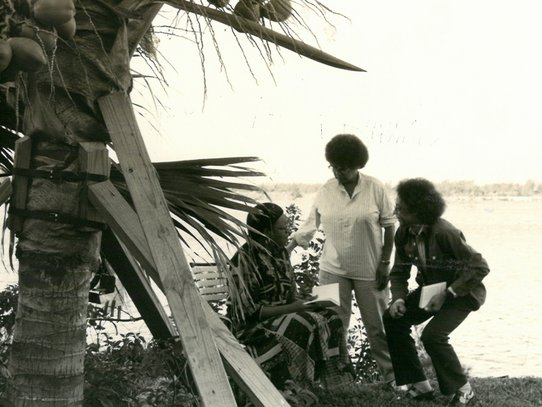

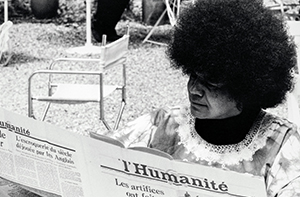

A tireless filmmaker, Sarah Maldoror—who died in 2020—ventured across many territories throughout a body of work comprising more than forty films: short and feature-length films, television dramas, reports, and documentaries. Her prolific output reveals her boundless curiosity, the plasticity of her imagination, and the richness of her ideas. Driven by political commitment, a deep belief in education, the power of history, and the necessity of transmission, the filmmaker produced numerous works on the history of Black thought, its heritage, and its heroes.

Driven by political commitment, a deep belief in education, the power of history, and the necessity of transmission, the filmmaker produced numerous works on the history of Black thought, its heritage, and its heroes.

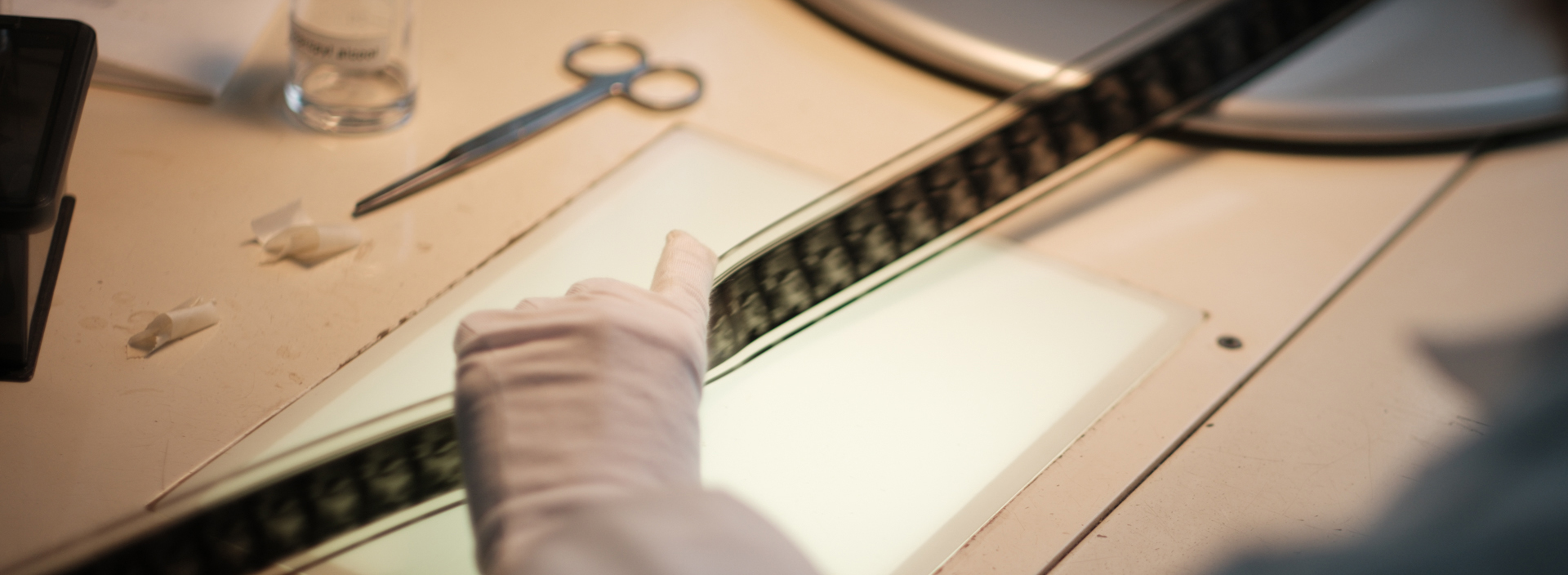

On screen, degraded footage alternates with restored images still in progress—here, highlights lack detail; there, the sound breaks up. A film is reborn before our eyes, and with it, the memory and vision of its director. Two more of her films are being restored at the same facility with the support of MansA – Maison des Mondes Africains: Et les chiens se taisaient (And the Dogs were Silent, 1978) and Aimé Césaire – Le masque des mots (Aimé Césaire – The Mask of Words, 1987), both receiving their world premiere screenings at the Centre Pompidou. At the helm is the filmmaker’s eldest daughter, Annouchka de Andrade, head of the Friends of Sarah Maldoror and Mario de Andrade Association, tirelessly working to highlight her parents’ intellectual legacy. An interview follows.

Why did you undertake this work on your mother’s oeuvre?

Annouchka de Andrade – When I began this project, my sister, Henda Ducados, and I shared the goal of bringing our mother’s work back to life—of recovering her memory. The first step was to track down the film prints and reclaim the rights. There were films we had never seen, or had forgotten. Some were missing altogether. My mother would sometimes lend master copies to festivals—those reference versions were then lost. Today, no trace remains of certain films! We’re still searching. Others are in very poor condition, either due to technical issues or storage conditions. All the films shot in the 1970s have shifted to red. For Sambizanga (1972), we had to return to the negative. For Et les chiens se taisaient (1978), we only had a 16mm print preserved at the CNRS [French National Centre for Scientific Research]. From that physical element, we carried out the restoration to retrieve a version as close as possible to the original, transferring it into today’s projection format. Restoring Sarah Maldoror’s films is a way of reviving her thoughts.

Why did some films disappear or remain unseen for so long?

Annouchka de Andrade – There are two main reasons for this: one is lack of access to prints, and the other is degradation of the materials. Sambizanga, for instance, couldn’t be screened for over forty years because the producer and distributor who owned the rights refused to grant us access. As for À Bissau, le carnaval (1980), it had turned entirely green, monochromatic. Out of respect for the work, it was better not to show it in that state. Thanks to the CNC [French National Centre of Cinema], we were able to restore it and now it’s circulating again. Et les chiens se taisaient was also restored from 16mm image and sound copies held by the CNRS, as the master was missing. We had to comb through all the available elements to reassemble the film. Its condition was quite poor: passable on a television screen, but a large-scale projection magnifies all the flaws.

Restoring Sarah Maldoror’s films is a way of reviving her thoughts.

Annouchka de Andrade

What does the restoration process actually entail?

Annouchka de Andrade – Everything depends on the condition and availability of the original materials. Sometimes, it’s just a matter of cleaning the film and running it through a bath—more of a preservation effort than a true restoration. But if the print is torn or damaged, every splice must be repaired before digitization. The lab works on it for several weeks, after which we review it together and make decisions on what remains to be done. For À Bissau, le carnaval, for example, it took a full day’s work in the lab to restore just twenty minutes of footage. We truly worked frame by frame, comparing different versions.

Do you aim to modernize the films, or stay faithful to their original form?

Annouchka de Andrade – The goal is never to remake the film. We strive to get as close as possible to the original version conceived and created by Sarah Maldoror. For her first short film, Monangambééé (1969), shot in Algiers, we faced a real issue with the sound: the sound negative was missing, and the audio on our working copy had badly deteriorated. The free jazz soundtrack by the Art Ensemble of Chicago—with its sharp breaks—intertwines with the dialogue. We chose to prioritize the sound atmosphere, even if that meant subtitling some muffled dialogue. We preferred preserving the film’s atmosphere and texture rather than smoothing it all out. It’s not about erasing the passage of time, but about enhancing it.

How do you make decisions during a restoration?

Annouchka de Andrade – Breathing new life into these films is a fascinating process, but also full of uncertainties: have we done too much? Have we respected the film’s inherent boundaries? Here at the lab, we constantly question ourselves, consulting with the team to find the best solutions. No two restorations are alike. For Sambizanga, for instance, we were able to work with the original cameraman. Jean-François Robin came in person and worked shot by shot, in the screening room. Who better than him to carry out this task?

What does this retrospective at the Centre Pompidou mean to you?

Annouchka de Andrade – My mother was absolutely passionate about museums. That this first French retrospective is taking place at the Centre Pompidou feels deeply meaningful. For me, it’s almost natural to be here—it aligns with who she was. Sarah Maldoror is also featured in the Paris noir exhibition; we’re presenting documents and artworks she collected. It reveals just how deeply she loved artists, how she was an integral part of the intellectual currents of her time. The retrospective and exhibition are both significant—and it’s wonderful they’re happening in Paris today. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

© Pierre Malherbet

© courtesy Annouchka de Andrade et Henda Ducados

© Ass. Les Amis de Sarah & Mario