Sarah Maldoror: Cinema as a Form of Combat

“Cinema is an art of the present. It’s not about yesterday or tomorrow—it’s about today!” This unequivocal declaration, characteristic of Sarah Maldoror’s fiery spirit, shaped the course of her entire body of work. She was both a filmmaker and an activist—two dimensions that sometimes diverged and then converged again, a dynamic that is key to understanding her cinema. Maldoror worked through images; she began her career as an actress and was a co-founder, in 1956, of the theatre company Les Griots, alongside Ababacar Samb Makharam, Timité Bassori, and Toto Bissainthe—the first theatrical troupe in France composed entirely of Black actors.

African women must be everywhere. They must be in the images, behind the camera, in the editing room, and involved in every stage of filmmaking.

Sarah Maldoror

Her cinema responds to a sense of urgency—an urgency rooted in the very conditions of her formation: a solitary woman, orphaned, without means, arriving in Paris after years spent in the south of France, years marked by being the only Black person—and all the violence that entails. Paris, a city alive with the global effervescence of nègre arts, became the site of transformative encounters. It was there that she chose a new name, a name of her own—an act of taking her place in literature and poetry, forging unbreakable ties with poets and activists: the Brazilian Mário de Andrade, the American Langston Hughes, and the Frenchman Aimé Césaire.

Struggle and the mask

With over forty films to her name, her body of work closely accompanies the major intellectual and political movements of the 20th century—Négritude, Pan-Africanism, feminism, and communism—tirelessly questioning and documenting, through cinema, the struggles for the emancipation of peoples. Sarah Maldoror accomplished a great deal, yet there is also all that remains unrealized: forty-six projects that never came to fruition.

With over forty films to her name, her body of work closely accompanies the major intellectual and political movements of the 20th century—Négritude, Pan-Africanism, feminism, and communism—tirelessly questioning and documenting, through cinema, the struggles for the emancipation of peoples.

She settled in Algiers with her family in the mid-1960s. At that time, the city was a vibrant centre of anti-colonial struggle. It was there that she shot Monangambééé, her first short film, completed in 1969, a work that serves as a prelude to her second feature, Sambizanga, filmed in Congo-Brazzaville and released in 1972, following the loss of Des fusils pour Banta—shot in 1970 and still missing to this day.

These two films—now recognized as the filmmaker’s masterpieces—are radical indictments of the violence of colonial domination. They focus on portraying the everyday lives of Angolan revolutionaries fighting against Portuguese oppression. With meticulous attention, Maldoror depicts the strength of collective structures—couples, families, political movements—as vital foundations for resistance. In À Bissau, le carnaval (1980), a short film capturing the festivities of carnival ceremonies, this theme resurfaces, affirming community as a condition of endurance. One of the opening sequences of Sambizanga, showing Maria and Domingo waking in their hut with their baby nestled between them—moments before the father is arrested—embodies the unmatched emotional force of Maldoror’s cinema.

Forced to return to Paris in the early 1970s, she settled in Saint-Denis. From then on, she developed a multifaceted body of work interweaving poetry, music, and literature. Restlessly creative, she alternated between short, medium, and feature-length formats—many of them produced for television—based on her travels and the encounters they inspired.

Between 1979 and 1980, she dedicated a trilogy of films to the Cape Verde Islands—Fogo, île de feu; À Bissau, le carnaval; and Un carnaval dans le Sahel—made shortly after the islands gained independence. Today presented as a cohesive series, the films critically explore the symbolic and political power of the mask.

In “I’m Only Interested in Women Who Struggle”, a text on Maldoror, Jeremy Harding notes that in Le Masque des mots (The Mask of Words, 1987)—one of five films Maldoror devoted to Aimé Césaire—the Martinican poet states: “When I write a poem, I appear to myself as someone wearing a mask.” This gesture could just as well describe the cinematic practice of Sarah Maldoror.

Sarah Maldoror in “Paris noir”

In “Paris noir”, Maldoror appears as an artist who guides us towards other artists—introducing them, offering them to us, helping us to understand them—just as she does in her films. Her deep sensitivity to the visual arts must also be acknowledged: every Sunday, she could be found at a museum. In any new place, what she sought out first were museums, cemeteries, and prisons. A method. That of a keen observer. One who filmed her artist friends with remarkable tenderness and insight.

Her final film is dedicated to the Colombian painter Ana Mercedes Hoyos—a work that brings to a close everything Maldoror sought to express about Black identity and the wealth built upon the blood of enslaved peoples. Maldoror’s films always begin with a visual reference—a painting, a sculpture—never by chance.

Maldoror’s films always begin with a visual reference—a painting, a sculpture—never by chance.

Et les chiens se taisaient (And the Dogs Were Quiet, 1978) must be mentioned—in “Paris noir” it sets the rooftops of the city ablaze. In this major work, Maldoror performs alongside Gabriel Glissant an adaptation of Aimé Césaire’s text, which stages the defiance of a rebel who refuses to submit to colonial oppression. The film was shot in the storerooms of the Musée de l’Homme, interweaving footage of African objects with views of the Martinican landscape. Maldoror transforms this colonial symbol into a space for revolt, restoring fertility to a site whose role in preservation also participates in a system of loss, erasure, dissociation, and epistemological rupture—the machinery of death.

The film bears witness to her deep friendship with the author of Discourse on Colonialism (1950), to whom she dedicated four films, including a filmed portrait in 1976 (Aimé Césaire, un homme une terre). Her connection to emblematic figures of Pan-African struggle is further illustrated in a series of short poetic films—on view in the exhibition—that bring us face to face with Depestre, Senghor, Damas, and Bissainthe, in a form unlike any other.

Et les chiens se taisaient echoes Sarah Maldoror’s stance, powerfully voiced as early as 1958 in an interview with Marguerite Duras about the Les Griots production of Jean Genet’s Les Nègres: “We need you to learn to know us through a relationship of equality, and to forget even what you were taught at school about Negroes.” ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

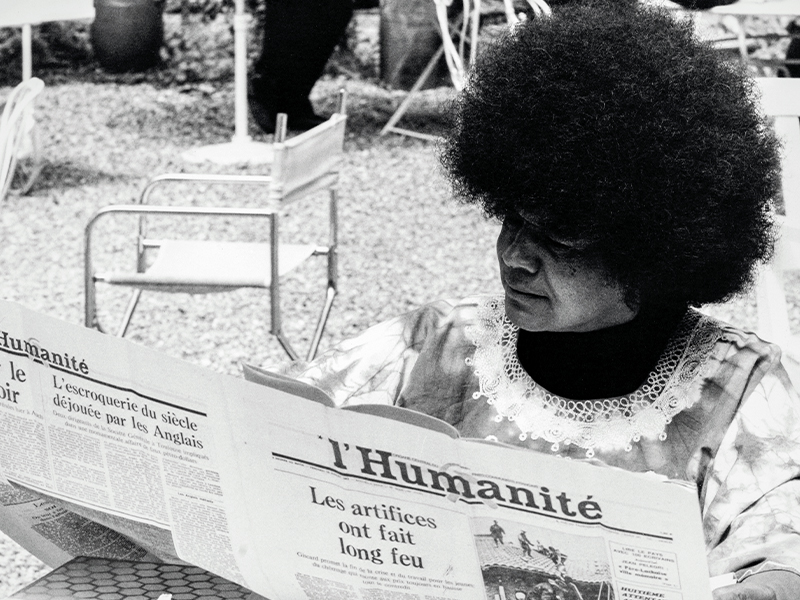

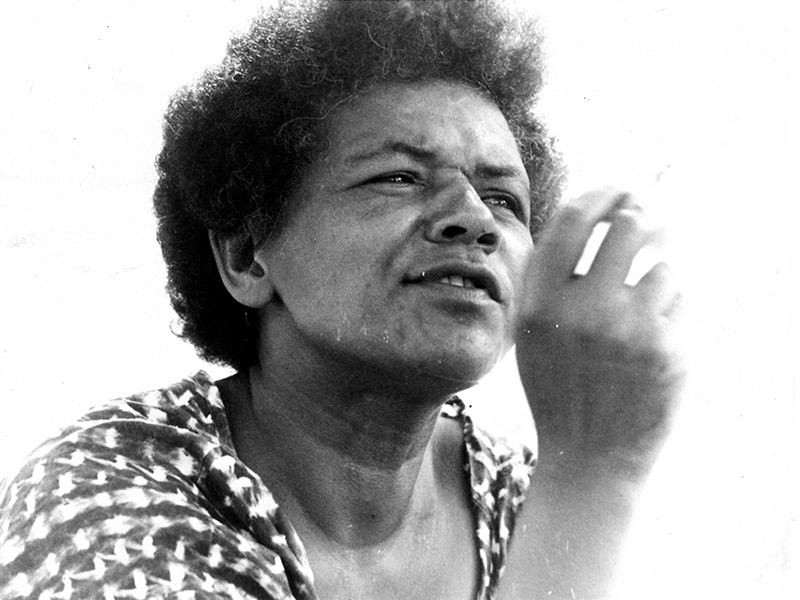

Portrait de Sarah Maldoror

Photo © Gérald Bloncourt