![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/user_upload/Ted-Joans-bandeau.jpg)

A "Sentimental Teducation", by Jake Lamar

I.

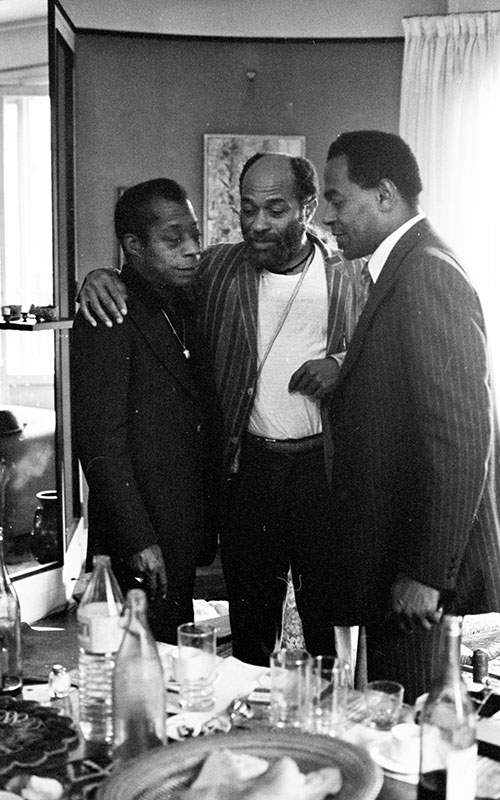

Autumn 1993. I arrived in Paris, at age 32, following in the footsteps of my idols Richard Wright and James Baldwin, two giants of African American literature who had quit the USA for la ville lumière just after the Second World War.

But I was only going to stay in Paris for one year. That was the plan.

I had recently published my first book, a memoir (récit autobiographique) titled Bourgeois Blues (Confessions d’un fils modèle) about my relationship with my father and how our lives reflected the evolution of racial politics in the USA between the 1930s and the 1980s. Now, I was under contract for my second book, and first novel, a satirical political thriller that would become The Last Integrationist (Nous Avions un Rêve). I had also won a generous grant called the Lyndhurst Prize.

I knew very few people in Paris. I didn’t speak a word of French. But I thought I would indulge my curiosity about Paris for this one year. Explore the city while I finished writing my novel. Then I would go back to the USA and get a job teaching journalism or creative writing at a university. I would allow myself twelve months of this Parisian adventure, then I would go home, in search of security, stability, respectability.

Instead, I met Ted Joans. And received a life-altering course in Teducation.

I don’t remember how I learned that Ted Joans would be giving a poetry reading at a little Left Bank bookshop (which no longer exists) called Tea and Tattered Pages. I knew the name Ted Joans, recognized it from an anthology of Black American poetry that I had read in high school. But I knew nothing about the man himself. The bookshop was quaint, cozy, and packed. I struck up a conversation with another audience member, a brilliant and charismatic artist named Carrie Mae Weems. She was spending a year at the Cité des Arts and still in the early phase of her illustrious career.

Ted Joans had a bushy gray beard, wore a black beret and thick-framed eyeglasses. He began to read and I was immediately awestruck, astonished. He opened, as I would learn was customary, with his poem The Truth, a sort of personal anthem, a bold assertion of visionary integrity: “You have NOTHING to fear / from the poet / but the TRUTH.”

Ted Joans reads his poetry the way Dizzy Gillespie plays the trumpet.

As he continued to recite other works, I instantly recognized something in his unique style: Ted Joans reads his poetry the way Dizzy Gillespie plays the trumpet.

He continued with a comic epic of a poem titled Why I Shall Sell Paris. Like a bebop style auctioneer, he touted all the precious monuments for sale, mocking tourism, commercialism and French nationalism all at once: “I shall sell the biggest jive boulevard in the world: Champs Élysées / I shall sell every bridge that double crosses the River Seine.” I burst out laughing when he announced, in his jagged, rhythmic cadence, that he would sell “Place de la Concorde Yet without the Obelisk It shall be returned to Luxor in Egypt.”

Ted Joans was advocating cultural restitution long before it became a cause célèbre.

The style and substance of his poems represented Ted Joans’s now-famous self-definition: “Jazz is my religion, surrealism is my point of view.”

I walked up to the poet after his reading. A young woman hovered nearby, snapping photos. I would later learn that this was Ted’s partner, Laura Corsiglia, a gifted Canadian student at l’École des Beaux Arts. I introduced myself, told him how much I loved his work. Ted told me I should visit him the next day at his Paris headquarters, the Café Le Rouquet on the Boulevard Saint-Germain.

Jazz is my religion, surrealism is my point of view.

Ted Joans

II.

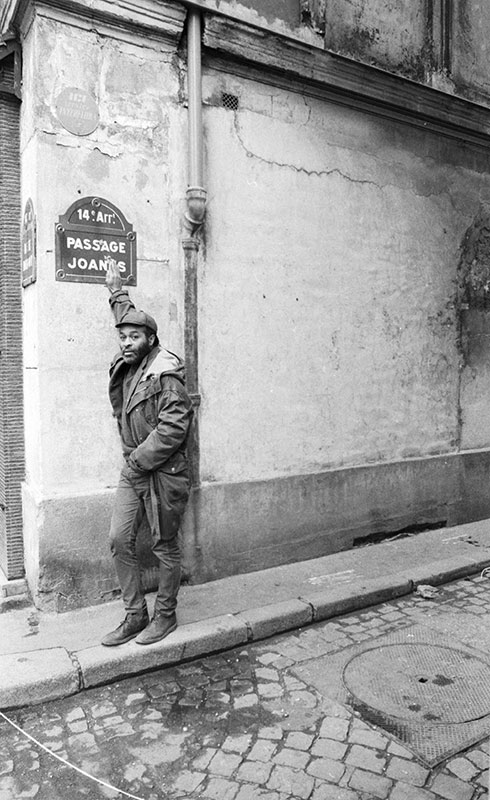

By January, 1994, I had become a regular visitor to the corner terrasse table of Ted Joans, where, as he wrote in his poem, Chez Le Café Le Rouquet, he sat “Afternoons of each / When-In-Paris-Day.”

I was lucky, those early months in Paris, since Ted told me he usually went to his home in Timbuktu, Mali this time of year, in part to escape the cold and gray of the Paris winter. But this year he was often at the brightly-lit Saint-Germain café with an interior design charmingly frozen in the 1950s. If I arrived and Ted was alone, he was always either reading, drawing or writing in a notebook. But always happy to set aside his work and chat. Sometimes Laura would be there, serenely drawing in a sketchpad and joining in the conversation.

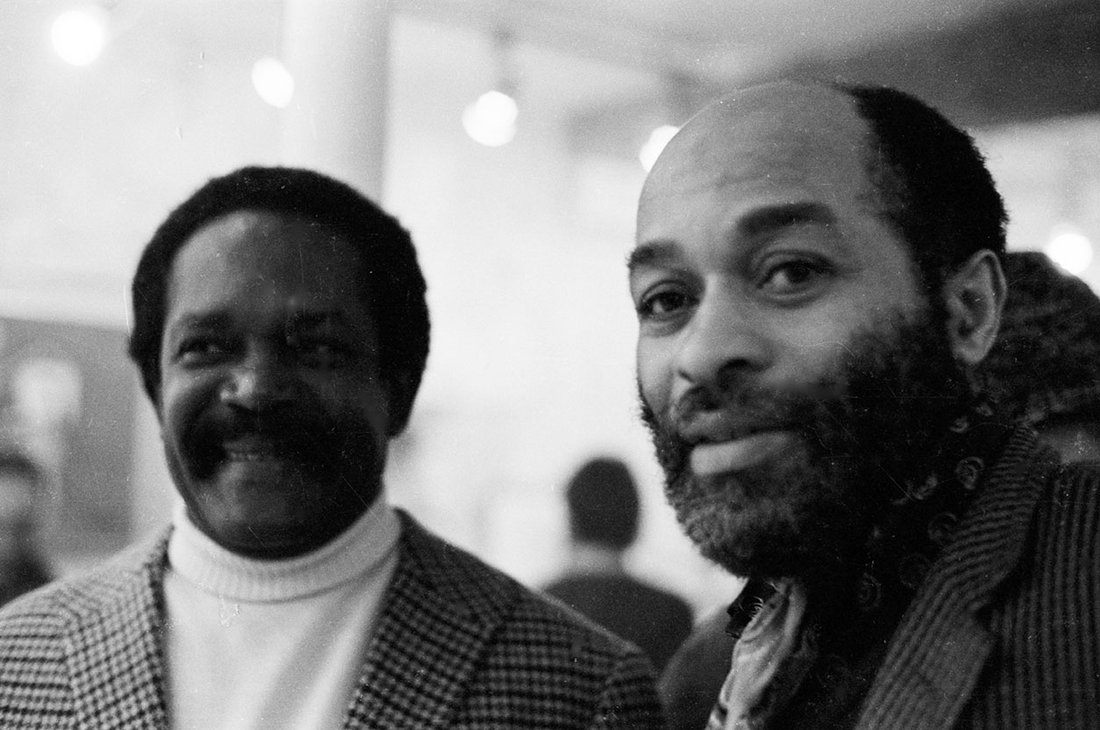

The very first time I visited the café, the day after the Tea and Tattered Pages reading, Ted was sitting with two other Black American men his age: Hart Leroy Bibbs, a grizzled, gravelly-voiced artist and poet who always wore a green fedora; and James Emanuel, a noted poet and scholar, who exuded a cool, quiet dignity. Talking with these three wise elders that drizzly afternoon, a strange feeling came over me. Until then, I’d felt very isolated in my situation as a writer, alienated from prevailing American notions of how a Black Author was supposed to think and express themselves. Sitting with Ted, Bibbs and James, I felt that I was beginning to find my true place, my real community, right there at that café table.

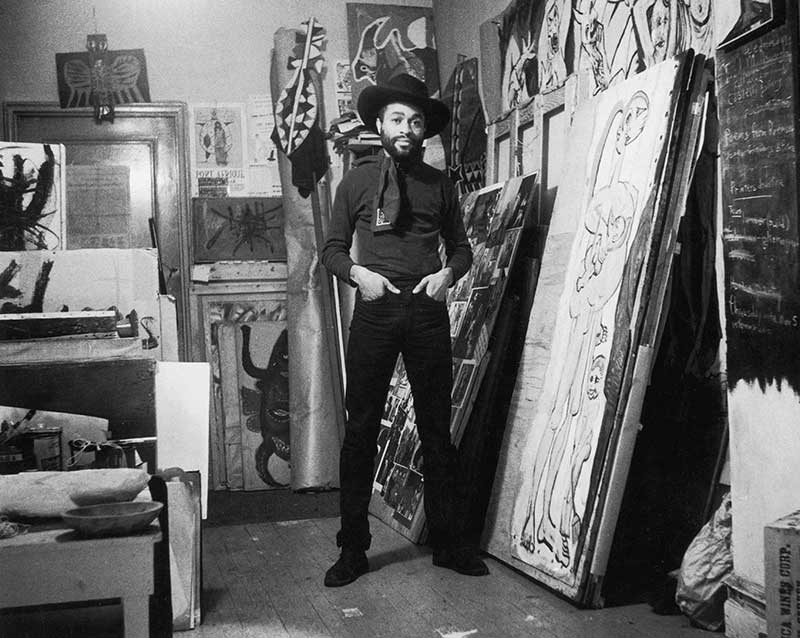

Ted Joans was a poet, painter, trumpet player, collagist extraordinaire, raconteur and ceaseless traveler, an artist whose life itself was a sort of work of art.

And I was about to join the legions of people around the world, from all walks of life, who would be enchanted by the protean creative force that was Ted Joans. He was not just the Jazz Poet, mentored by Langston Hughes in Harlem, that I’d seen the night before. Ted Joans was a Surrealist, mentored in Paris by the founder of the movement, André Breton. Ted Joans was a founding father of the Beat Generation, one of the original Hipsters, reciting his poetry in Greenwich Village coffeehouses in the 1950s and hanging out with Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Gregory Corso. He was a proud pan-Africanist and Black Power militant who had traversed the Sahara Desert multiple times. He had frequented the circle of American expat writer Paul Bowles in Tangier. He’d chanted his poems to the accompaniment of the Archie Shepp Orchestra in Algiers. Organized sexually charged Happenings in Copenhagen in the 1960s. And back in his Greenwich Village days, he had shared a flat with the great god of bebop, Charlie “Yardbird” Parker. When Parker died in 1955, Ted Joans became one of the world’s first famous graffiti artists, scrawling “BIRD LIVES!” on walls all over New York City.

Ted Joans was a poet, painter, trumpet player, collagist extraordinaire, raconteur and ceaseless traveler, an artist whose life itself was a sort of work of art. He spoke of leading a poem-life, guided by the Surrealist principle of Objective Chance, a sort of serendipity or synchronicity, finding human connection through accidental, uncanny encounters, searching for the secret patterns in seemingly random coincidences. He seemed to bear some precious knowledge that was just out of reach for most of us. He wanted to teach us, aptly dubbing himself a griot surrealiste. His series of sublime Super-8 movies were called Teducation films. Teducation is also the title of his indispensable collection of selected poems, published in 1999.

And during my early months in Paris, I received an immersive Teducation: an appreciation of spontaneity, of effervescent ephemera, an eager openness to new experiences, the courage to follow creative impulses and to reject conformity. To forget about stability, security, respectability. To dare to live improvisationally. To dare to live the life that I loved.

III.

If, in any given year, Ted Joans happened to be in Paris, on February 1st, he organized a reading at Shakespeare and Company Bookshop to celebrate the birthday of Langston Hughes, the mentor he called the greatest Black poet, who had, in a classic phrase of Ted’s, “gone on to the ancestors” in 1967.

On February 1st, 1994, Ted invited me to join him, Hart Leroy Bibbs and James Emanuel in the Hughes celebration. Ted, Bibbs and James, all mesmerizing poets, read selections of their own works and poems by Hughes. Since I had no poetic talent to speak of, I read from essays, one of mine, one of Hughes’s. I felt a bit insecure about my reading. But Ted, after having read his magnificent poem dedicated to Hughes, handed me a copy of the work, Passed On Blues: Homage to a Poet.

“Un cadeau,” Ted said. “I think Langston would have wanted you to have this.”

“Merci,” I said, trying not to get misty-eyed.

Ted popped open a bottle of champagne and we all drank a toast to Langston.

By June 1994, nine months after I’d arrived in Paris, I was ready to extend my planned one-year stay. I wasn’t sure how I would make a living, I just knew I wanted to live in Paris. I scribbled in a notebook:

You’re always looking one way when some surprise, pleasant or otherwise, hits you from the opposite direction. Expect the unexpected.

My Teducation was kicking in. I stayed in Paris a second year, then a third year, then met la femme de ma vie. It was the ultimate uncanny encounter. After thirty-two years, I’m still living the Paris Noir life.

IV.

Ted Joans continued to trot around the globe, almost always accompanied by his soulmate Laura, who had blossomed into an extraordinary artist. Every once in a while, I would receive a letter or postcard from Ted, addressed to “His Hipness Jake Lamar,” letting me know when he’d next be in Paris and ready for a rendezvous chez le Café Le Rouquet.

I’m a Marxist. A Groucho, Chico, Harpo Marxist.

Ted Joans

I saw him there on March 24th, 2003. Ted was unwell, a bit frail. The United States had just launched its “shock and awe” invasion of Iraq. A huge anti-war march was advancing down the Boulevard Saint-Germain. As I entered the café, a young man was walking away from Ted’s corner table on the terrasse. He hurried out the door and rejoined the demonstration.

I scribbled in a notebook sometime later:

One of the marchers, a Malien, had rushed in the café, shook Ted’s hand. Ted didn’t recognize him but the young man said he had attended a reading of Ted’s in Mali years ago. Ted had inspired the young man to become a writer.

Ted and I watched the demonstration disappear down the boulevard. Ted said politics never really suited him. “I’m a Marxist,” he said. “A Groucho, Chico, Harpo Marxist.”

We took a walk around the Latin Quarter. I knew that Ted knew this would be his last visit to Paris. The neighborhood was full of memories for him. One typical moment: Ted pointed to the balcony of a building and said, “That was where I saw Miles Davis for the last time.”

A few weeks later, Ted Joans went on to the ancestors. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

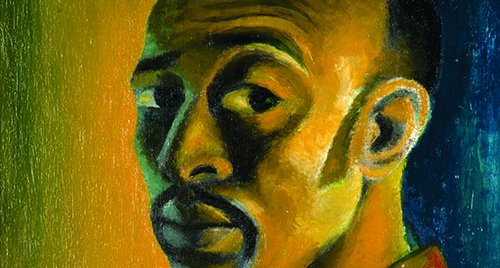

Portrait of American painter, poet, and musician Ted Joans (1928 - 2003) as he stands in his loft apartment, New York, 1959.

Photo © Fred W. McDarrah/MUUS Collection via Getty Images