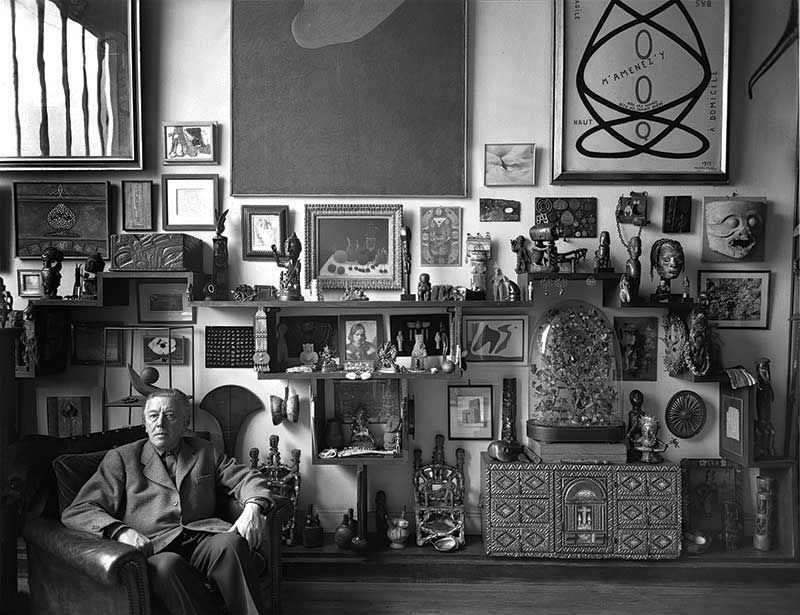

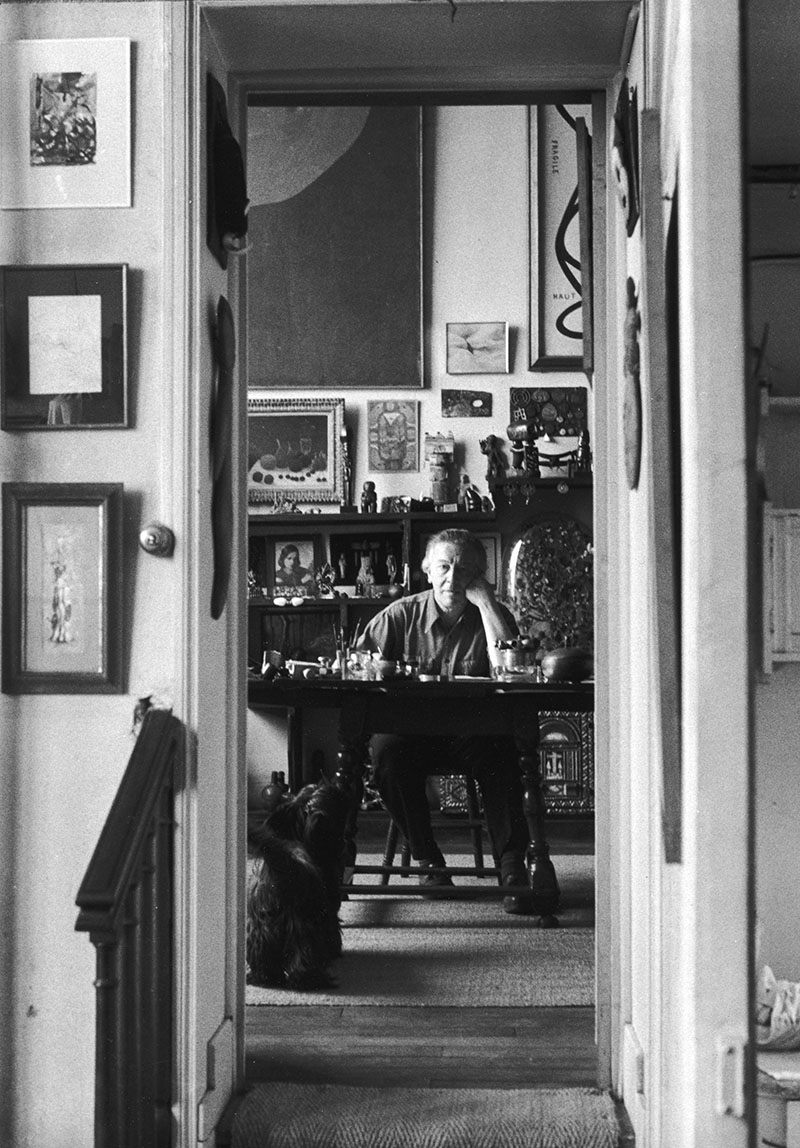

Chez André Breton, at 42 Rue Fontaine, Paris

Those visiting André Breton’s studio, who crossed the threshold of 42 Rue Fontaine, would recognise from the small plaque, marked “1713”, affixed to the door that they had arrived. The numbers 17 and 13 were chosen by Breton for their graphic resemblance to the letters A and B, his initials. This subtle touch of mystery at the entrance to the studio, which he occupied for nearly forty years, offered a glimpse of the timeless journey awaiting visitors to this space. Situated at the foot of Montmartre, it was nevertheless at the heart of Paris’s nocturnal life.

From the early days of his marriage to Simone Kahn in 1922 until his death in September 1966, the founder of Surrealism lived in this studio, moving down one floor in 1949 to gain an additional room for his 14-year-old daughter, Aube.

From the early days of his marriage to Simone Kahn in 1922 until his death in September 1966, the founder of Surrealism lived in this studio, moving down one floor in 1949 to gain an additional room for his 14-year-old daughter, Aube. The only interruption to his life in this unique space was his exile in New York between 1938 and 1945. The studio was not only a point of reference for his writing and a mental compass but also the headquarters for the group’s early collective declarations.

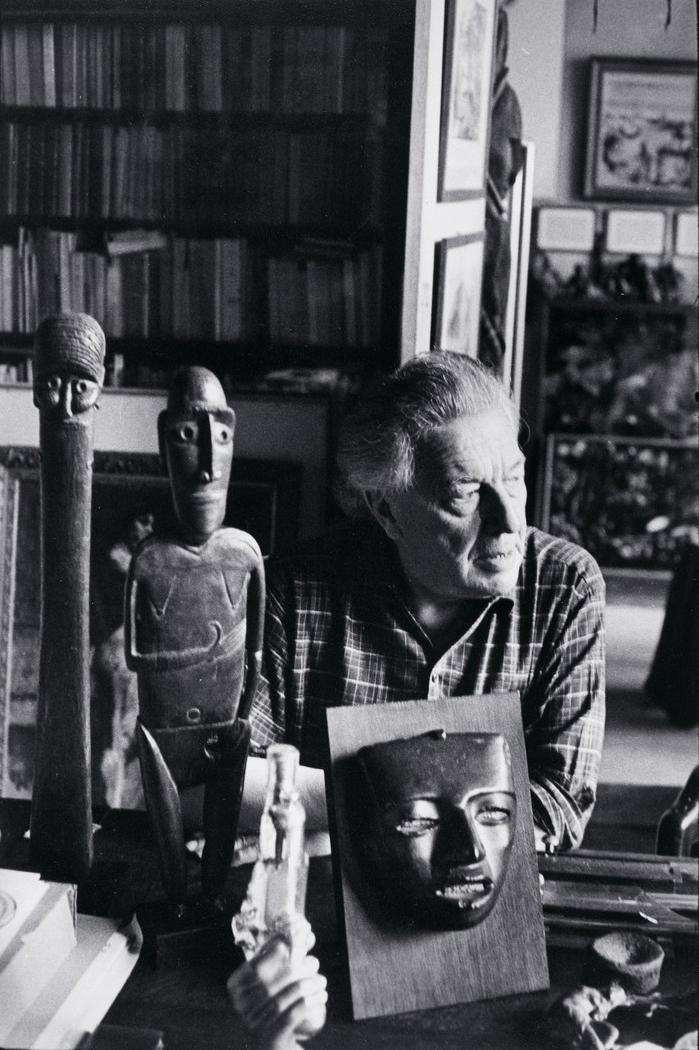

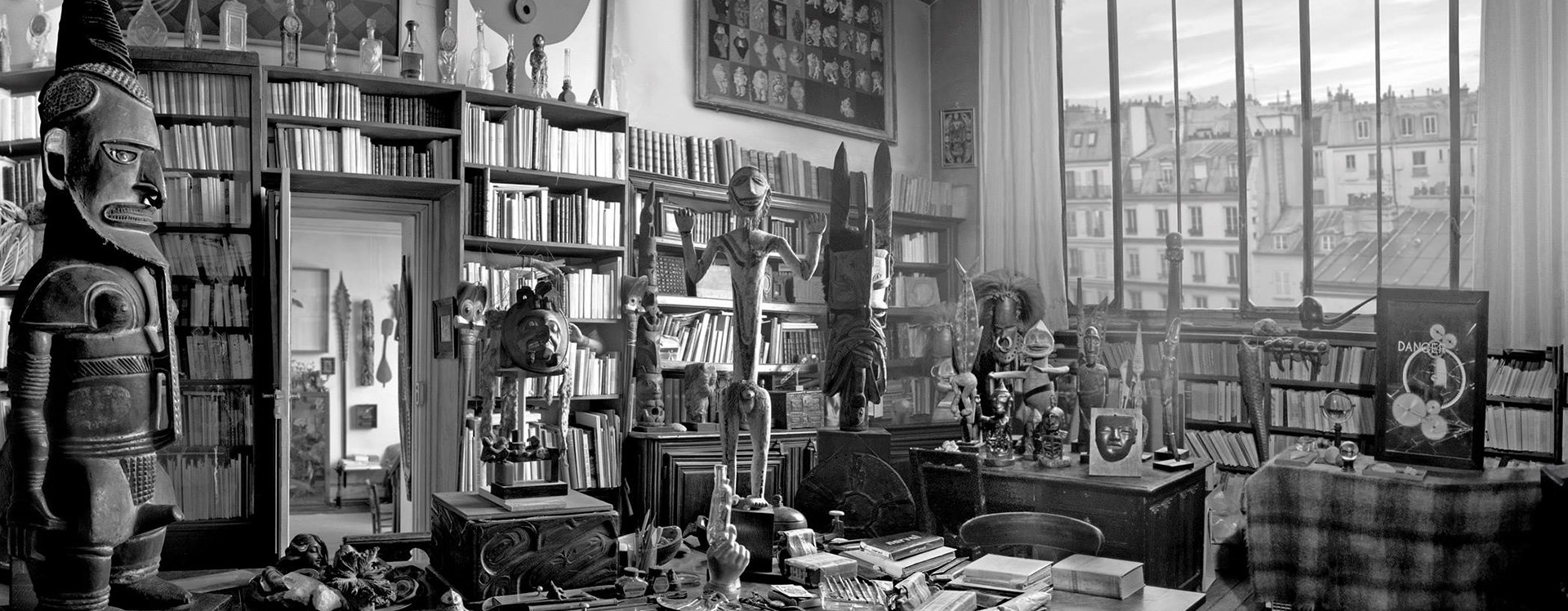

The apartment’s two main rooms contained more works and objects than seemed possible. To grasp Breton’s collecting passion and his obsessive quest for the perfect object, one must go back to his foundational story: in 1917, Breton purchased the first piece in his collection using money from his baccalaureate—a moai kavakava figure from Easter Island. This was the beginning of a collection that would only end with his death. The omnipresence of objects surrounding the founder of Surrealism reflected the singularity of his vision and the mental laboratory where artworks were arranged and rearranged, rejecting any hierarchy among surrealist artists—Joan Miró and Alberto Giacometti amongst them—or great precursors like Victor Hugo and Alfred Jarry.

The collection also included Oceanic artifacts (primarily from Papua New Guinea and Polynesia, such as the Marquesas Islands), Native American and pre-Columbian objects (mainly from Mexico, which Breton visited in 1938), as well as popular and natural art pieces. Together, they filled what Breton called his “ideal surrealist palace”, a space that remains his most mythical.

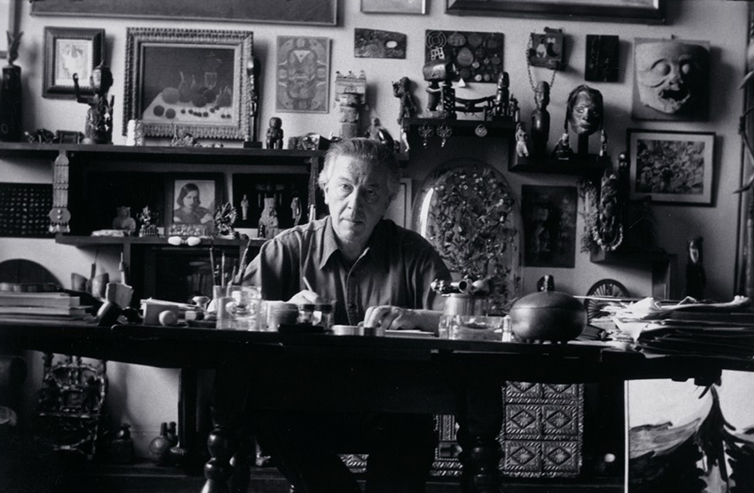

The wall behind André Breton’s desk, covered with some 255 objects—masterpieces alongside simple stones and minerals picked up during walks along the Lot River—was the most striking feature of his studio.

In 2003 the Centre Pompidou acquired a fragment of this exceptional collection. The wall behind André Breton’s desk, covered with some 255 objects—masterpieces alongside simple stones and minerals picked up during walks along the Lot River—was the most striking feature of his studio. Twenty years after its inclusion in the collection, through a historic donation by the poet’s daughter, Aube Breton-Elléouët, a book titled Mur Mondes. L’atelier d’André Breton undertakes a detailed study of these objects. The Breton Wall traces the intertwined history of a collection and the development of a critical perspective on modernity.

On January 1, 1922, Breton moved into a building near Place Blanche with his first wife, Simone Breton (née Kahn). Located close to Paris’s nocturnal life, including the aptly named cabarets Ciel and Enfer, the studio comprised two main rooms overlooking Boulevard de Clichy. The writer Julien Gracq, a regular visitor in Breton’s later years, described the persistent impression of darkness, despite the presence of large studio windows. This atmosphere mirrored Surrealism itself, which, from its first manifesto in 1924, embraced the ambiguity of shadows far more than the brazen sunlight of noon.

Located close to Paris’s nocturnal life, including the aptly named cabarets Ciel and Enfer, the studio comprised two main rooms overlooking Boulevard de Clichy. The writer Julien Gracq, a regular visitor in Breton’s later years, described the persistent impression of darkness, despite the presence of large studio windows.

A focal point for Breton’s work, a space for surrealist group meetings and ‘sleep sessions’, for everyday life and private moments, the “first studio” (before the war) was described by Simone Breton in her letters as a “room of noise and light”, with a second room of “silence and shadow”. Together, they laid the foundation for one of the 20th century’s most forward-looking collections.

In 1921, Breton became the artistic advisor to couturier and collector Jacques Doucet. While Doucet had far greater means, Breton guided him towards acquiring some of the most iconic works of modernity, such as Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Rousseau’s The Snake Charmer (1907) and Duchamp’s Rotary Glass Plates (1920). This curatorial apprenticeship informed Breton’s own collecting ethos, centred on a ‘wild eye’ aesthetic and an interior model of the marvellous.

A pioneer in art and a theorist of an aesthetics of the marvelous rooted in an "inner model," André Breton championed what he called, in Le Surréalisme et la peinture (1928), "the eye exists in a wild state." Over the course of his life, he assembled an extraordinary collection, remarkable both for its scope and for the singularity of its aesthetic choices.

Over the course of his life, Breton assembled an extraordinary collection, remarkable both for its scope and for the singularity of its aesthetic choices.

By the 1930s, his collection of surrealist art, Oceanic artifacts (primarily from Papua New Guinea), Native American works, pre-Columbian objects from Mexico, popular art and naturalia found its home on a tiered wooden shelf designed by Breton. This striking arrangement was crowned with three major paintings by Francis Picabia, Joan Miró and Jean Degottex, symbolising three distinct moments in Surrealism: the Dada period, 1920s Surrealism and 1950s gestural abstraction. The current reconstruction faithfully replicates the layout of the studio’s second room as it was at the time of Breton’s death.

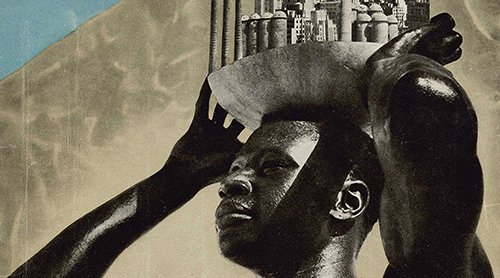

However, the objects were not always fixed. Historical photographs show the wall evolving with new acquisitions or sales, such as the dispersal of Breton and Paul Éluard’s African and Oceanic art collections during the “Exposition Coloniale Internationale” held in Paris in 1931—a paradoxical act given Surrealism’s condemnation of colonialism, yet reflective of its entanglement with modernity’s contradictions.

This colonial dimension is critically addressed for the first time in the book Mur Mondes. While Breton passionately advocated for the emancipation of oppressed peoples and denounced colonialism, he continued acquiring objects of colonial provenance. For him, these objects were ‘survivors’, reclaimed into the circuit of surrealist wonder, with the "Mur Breton" both defending and illustrating this ethos. Breton viewed objects as poetically omnipotent, often eclipsing other considerations.

André Breton viewed objects as poetically omnipotent, often eclipsing other considerations.

After returning from American exile in 1946, the studio’s objects became its true inhabitants. By the 1960s, as Breton opened his studio to increasing photographic reports, he described his unique interior: “On the walls, works by Chirico, Max Ernst, Picasso, and Miró. A marked taste for so-called ‘naive’ art. A collection of ethnographic objects, with a preference for Oceanic art and the art of Native Americans. A wall of Eskimo masks facing a wall of Hopi dolls, gathered one by one in Arizona’s reservations. A cabinet of hummingbirds, another large enough to hold several birds-of-paradise, the Argus pheasant of New Guinea, and the lyrebird.

This love for disjunction and sparks of connection encapsulates much of Surrealism’s aesthetic programme. Breton, as his daughter Aube Breton-Elléouët aptly described, was a “definitive personality” as faithful to his chosen objects as he was uncompromising in demanding “absolute Surrealism”—a principle that often excluded women.

At the heart of Surrealism lies the belief that objects reveal the desires of their possessor, desire for Breton being synonymous with his aesthetic project.

The "Mur Breton" —or rather the 255 objects it comprises—was once a locus of transactions and geographic circulations. At the heart of Surrealism lies the belief that objects reveal the desires of their possessor, desire for Breton being synonymous with his aesthetic project. This reveals the greatest ambivalence of Surrealism’s emancipatory vision: the freedom of one often came at the cost of another. The objects of Breton’s studio wall remain an extraordinary historical testament, a bridge between the exaltation and melancholy of the ‘completely other’. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

A view of André Breton's studio-appartment

© Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Centre Pompidou