Exhibition / Museum

Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevitch...

The Russian avant-garde in Vitebsk (1918-1922)

28 Mar - 16 Jul 2018

The event is over

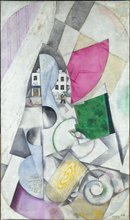

The exhibition devoted by the Centre Pompidou to the Russian avant-garde between 1918 and 1922 focuses on the work of three of its iconic figures: Marc Chagall, El Lissitzky and Kasimir Malevich. It also presents works by teachers and students of the Vitebsk art school founded in 1918 by Chagall: Vera Ermolayeva, Nicolai Suetin, Ilya Chachnik, Lazar Khidekel and David Yakerson.

Through 250 works and documents never seen together before, this event sheds light for the first time on the post-revolutionary years during which the history of art was written in Vitebsk, a long way from Russia's big cities.

When

11am - 9pm, every mondays, wednesdays, fridays, saturdays, sundays

11am - 11pm, every thursdays

Late opening: Thursdays (11 pm.)

Where

Curator's point of view

A hundred years ago, Marc Chagall was appointed commissar for fine art for the city of Vitebsk, today in Byelorussia. This appointment, soon followed by the opening of the Vitebsk School of Art on Chagall’s initiative, marked the beginning of a period of effervescent artistic activity in the city. Among the artists Chagall invited to teach at the new institution were leading figures of the Russian avant-garde such as El Lissitzky and Kasimir Malevich, inventor of Suprematism. If the Centre Pompidou’s exhibition devoted to this Russian avant-garde at Vitebsk from 1918 to 1922 has the work of these three major figures at its heart, it also includes work by students and other teachers at the school: Vera Ermolaeva, Nicolai Suetin, Ilya Chashnik, Lazar Khidekel and David Yakerson. Through some 250 works and documentary items this ground-breaking exhibition explores for the first time those early post-revolutionary years when, far from Moscow and Petrograd, the history of art was being made in Vitebsk.

This little-known chapter in the history of art begins with Marc Chagall. A painter living in Petrograd, this former inhabitant of the La Ruche artist’s colony in Paris was a witness to the Bolshevik Revolution that swept through Russia in 1917. The passage of a law abolishing all discrimination on the basis of religion or nationality gave this Jewish artist, for the first time, full rights of citizenship in Russia. Chagall embarked on a period of creative effervescence, marked by the production of a series of monumental masterpieces. Every one of these large paintings seems like a hymn to married happiness, Double Portrait au verre de vin and Au-dessus de la ville, for example, showing two lovers, Chagall and his wife Bella, flying among the clouds, as free as air. All radiate the euphoria of the moment. As the months passed, however, Chagall began to feel that he ought to do something to help the young people of Vitebsk who had no access to an artistic education, to support those who like him came from modest backgrounds, notably the Jews. He then had the idea of opening a revolutionary school of art, open to all, without restriction of age, and free to attend. This scheme, which also provided for the establishment of a museum, accorded perfectly with Bolshevik values, and in August 1918 it was approved by Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar for Education. A month later he appointed Chagall a commissar for fine arts, his first task being to organise the festivities for the first anniversary of the October Revolution. Chagall invited all the painters in Vitebsk to create placards and banners from sketches, a number of which have survived, notably those by Chagall himself and those by the young David Yakerson. Chagall would later write, in his autobiography: “On October 25th, my multi-coloured animals hung all over the town, swelling with revolution. The workers marched up singing the Internationale. When I saw them smile, I was sure they understood me. The leaders, the Communists, seemed less gratified. Why is the cow green and why is the horse flying through the sky, why? What’s the connection with Marx and Lenin?”

When the celebrations were over, the new commissar put all his energy into the development of his school, which he wanted to be open to all styles, offering too a high level of teaching. He invited well-known artists from the great cities of Russia, such as Ivan Puni or Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, one of the leading figures of the traditional World of Art group. The school officially opened on 28 January 1919. Much admired by his pupils, Chagall had to struggle to make sure that the school ran as it should. While the first teachers left the school, others arrived, among them Vera Ermolaeva, who would later head the institution, and above all El Lissitzky, who took responsibility for printing, graphics and architecture. He insisted that his friend Chagall should invite the leading representative of the abstractionists, Kasimir Malevich. It didn’t take long after his arrival in November 1919 for the charisma of this exceptional theorist to galvanise the young students. Together with teachers aligned with the new tendency, they soon formed a group they called UNOVIS – an acronym meaning “Champions of the New Art”. One of their slogans was “Long live the UNOVIS party, which champions new forms of the utilitarianism of Suprematism”. The group designed posters, magazines, banners, signage and ration cards, and Suprematism thus percolated into every sphere of social life. Its members directed festivals and stage works, designed tram liveries, decorated building facades, built speakers’ platforms. Coloured squares, circles and rectangles appeared in the streets, on the walls of the city. Suprematist abstraction became the new aesthetic paradigm not just at the art school but of life in general. Trained as an architect, Lissitzky played a key role. With his extraordinary series of Prouns (projects for the affirmation of the new in art), he was the first to deploy architectural volume within the Suprematist picture plane, describing these as “interchange stations between painting and architecture.

During his years at Vitebsk, Malevich for his part devoted himself less to his painting – an exception being his masterly Suprematism of the Spirit – than to his theoretical writing and his teaching. Methodical and stimulating, this last attracted more and more students, leaving Chagall increasingly isolated. His dream of a school that would foster revolutionary art of all styles, a unifying principle that had also guided him in both assembling the museum collection and curating the first public exhibition in December 1919 – where canvasses by Vassily Kandinsky and Mikhail Larionov had hung alongside abstract works by Olga Rozanova – came to an end in the spring of 1920. Seeing his own classes gradually empty of students, Chagall decided in June to leave Vitebsk for Moscow. He felt bitter toward Malevich, whom he accused of having plotted against him. The works he did at that time, such as Paysage cubiste, can be read as a settling of accounts with the Supremacists, in derisive or ironic mode: in the centre of a Cubo-Futurist composition, holding a green umbrella, a very small figure (Chagall himself?), a last survivor of the painter’s poetic humanism, walks in front of the white building of the art school.

After Chagall’s departure, Malevich and the Unovis group, now in sole control, worked on “the construction of a new world”. Group exhibitions were staged, in Vitebsk, Moscow and Petrograd; local groups were set up elsewhere in the country, such as in Smolensk around Vladislav Strzeminski and Katarzyna Kobro, in Orenburg with Ivan Kudriachov, and in Moscow, where Gustav Klutsis and Sergei Senkin were joined by Lissitzky, who in the winter of 1920 launched the new Constructivist movement. With the end of the civil war in 1921-22, the political climate changed: seeking to establish social and ideological discipline, the Soviet authorities began to withdraw support from artistic currents that did not directly serve the interests of the Bolshevik Party. May 1922 saw the first and last class graduate from the Vitebsk school of art. In the summer, Malevich left for Petrograd, together with many of his students, to continue his reflections on a three-dimensional Suprematism, creating porcelain and utopian architectural models he called Architectones. Chagall’s people’s school of art had become a revolutionary laboratory for rethinking the world.

Angela Lampe

Source :

in Code Couleur, n°30, january-april 2018, pp. 20-25

Partners

In the shop