L'histoire secrète de Dominique et John de Menil, légendaires mécènes du Centre Pompidou

In 1941, Dominique and Jean de Menil visited MoMA. The young couple, having fled Paris as the Nazis advanced, had just settled in New York. Accompanying them was Father Marie-Alain Couturier. A passionate advocate of modern art and a friend of Marc Chagall, the Dominican friar introduced them to Manhattan’s museums and galleries, acting as their guide. (After World War II, Couturier would become a key figure in the revival of sacred art in France, commissioning Henri Matisse, Fernand Léger, and Germaine Richier to create church decorations.) Before a painting by Piet Mondrian, as Dominique struggled to grasp the Dutch artist’s radical abstraction, Father Couturier said to her: “You may not like it, but it is serious, and you have to take it seriously.”

Modern art would indeed become a very serious matter for Dominique and John de Menil. The couple would go on to rank among the most influential private collectors and patrons of the 20th century, amassing a remarkable collection of more than ten thousand works.

Modern art would indeed become a very serious matter for Dominique and John de Menil. The couple would go on to rank among the most influential private collectors and patrons of the 20th century, amassing a remarkable collection of more than ten thousand works. Their acquisitions spanned a vast range: Cycladic idols, Byzantine relics, African and Oceanic totems, as well as paintings, sculptures, and installations by Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, René Magritte, Alexander Calder, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, Frank Stella, Donald Judd, and many others.

A Consuming Passion for Art

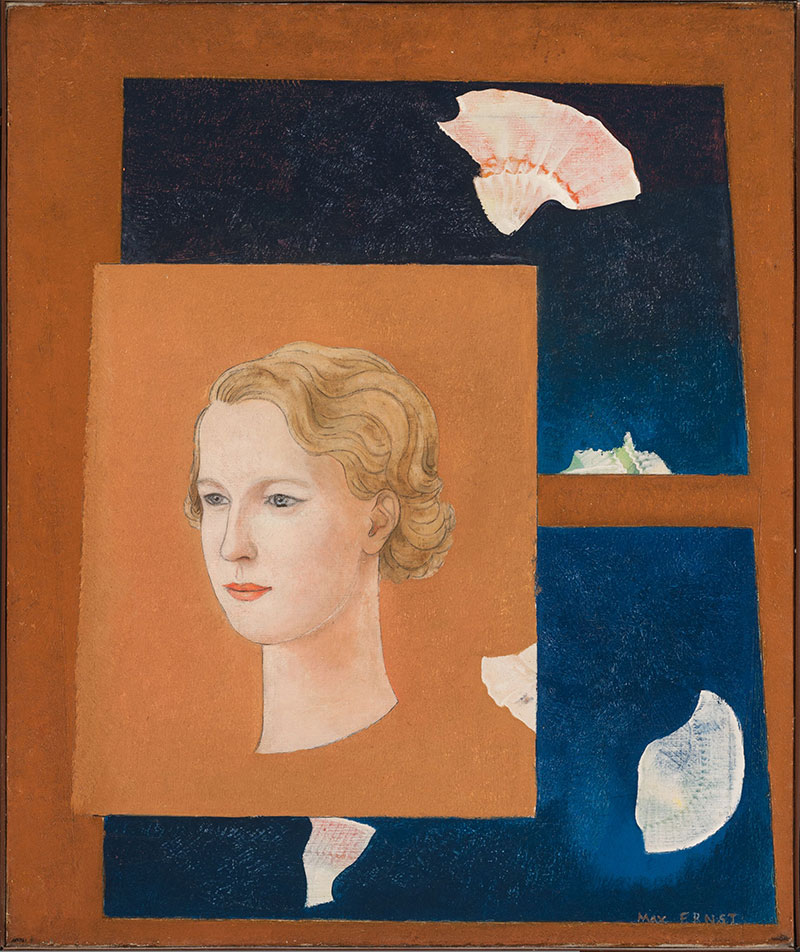

As early as 1931, the couple visited Max Ernst’s Paris studio to commission a portrait of Dominique—marking the beginning of their deep and abiding love for Surrealist art. In April 1945, once again following Father Couturier’s advice, John purchased a small, ethereal Cézanne watercolor titled Montagne (1895) from the Valentine Gallery in New York. In Double Vision—the definitive book on the de Menil collectors (Knopf)—author William Middleton recounts Dominique’s initial bewilderment at the price of the artwork : “It seemed like an awful lot of money for such a small amount of paint.” It’s a lovely little gouache,” she explained much later. “At first, I didn’t fall particularly in love, but now I understand. It’s a miracle of tension—the void means as much as the paint—and nobody is able to find that tension.”

As for Mondrian, her early hesitation soon gave way to a profound admiration for the abstract artist. In the 1950s, the couple acquired their first piece by him: Study for a Composition, a tiny preparatory sketch made on an envelope. Dominique cherished it so dearly that she once confessed that in case of a fire, it would be the one artwork she would save from the flames.

As early as 1931, the couple visited Max Ernst’s Paris studio to commission a portrait of Dominique—marking the beginning of their deep and abiding love for Surrealist art.

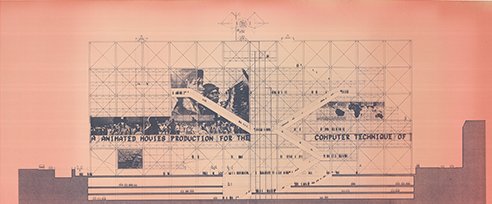

By 1987, the extraordinary collection they had painstakingly built finally found a home worthy of its scale: the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. Designed by Renzo Piano—his first project in the United States—the museum is an immense, light-filled steel structure painted white, and notably, admission is entirely free.

Nearby stands the renowned Rothko Chapel, an imposing octagonal building with black doors, housing fourteen paintings by Mark Rothko since 1971. Outside, visitors are greeted by Broken Obelisk, a monumental, fractured obelisk by Barnett Newman. Commissioned by the de Menils in 1969 as a gift to the city of Houston, the sculpture was intended to honor Martin Luther King Jr., a cause the couple ardently supported. When the city rejected the piece, Dominique and John chose to install it in their own park instead.

From Paris to Houston, Texas

For Dominique and John, it all began in 1930 at a ball in Versailles. Jean Marie Joseph Menu de Ménil was 26 at the time (he would later Americanize his name to John in the 1940s, dropping the accent on é). Born into an aristocratic family that had flourished under Napoleon before suffering financial setbacks, the young baron was an ambitious banker and a graduate of Sciences Po. At 5 feet 6 inches tall, Jean was not a natural seducer but rather a true dandy—always impeccably dressed in English-style suits, with custom-made shirts from Jeanne Lanvin’s atelier on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

At 5 feet 6 inches tall, Jean was not a natural seducer but rather a true dandy—always impeccably dressed in English-style suits, with custom-made shirts from Jeanne Lanvin’s atelier on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

Sharp-witted and quick-thinking (his friends nicknamed him Jean la comète—Jean the comet), he was also a man who enjoyed life’s pleasures. A regular at the famed brasserie La Coupole in Montparnasse—then a gathering place for figures like Ernest Hemingway, Man Ray, and André Breton—he moved with ease among the artistic and intellectual elite of his time.

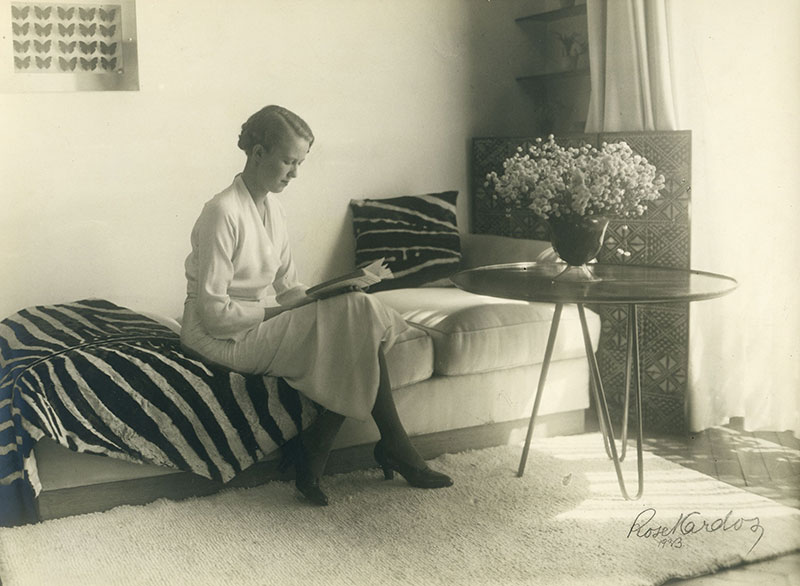

Dominique was 22 years old. A Parisian like Jean, she was born into the powerful Alsatian industrial family of the Schlumbergers. Her father, Conrad Schlumberger, and her brother, Marcel, had founded the oil exploration company of the same name in 1926 (now the multinational SLB). A philosophy graduate from the Sorbonne, the young woman—known for her steely blue eyes and strong-willed nature—had recently begun working in her father’s company.

A Parisian like Jean, Dominique was born into the powerful Alsatian industrial family of the Schlumbergers.

Fascinated by science, she also had a keen interest in cinema—she even interned on the Berlin set of The Blue Angel, starring Marlene Dietrich. A Protestant deeply influenced by her faith, Dominique would eventually convert to Jean’s Catholicism. The two married in 1931 and went on to have five children.

After a brief stay in New York, the couple settled in Houston, Texas, in 1941. With the war raging in Europe, Schlumberger had relocated its headquarters to this key hub for the oil extraction industry. John, who held various executive positions in his father-in-law’s company, played an active role in the group’s expansion. In the affluent and conservative neighborhood of River Oaks, the de Menils commissioned a house in the purest modernist style, designed by a then little-known architect—one Philip Johnson (who would later serve on the 1970 jury selecting the design for the future Centre Pompidou).

In the affluent and conservative neighborhood of River Oaks, the de Menils commissioned a house in the purest modernist style, designed by a then little-known architect—one Philip Johnson.

Legend has it that sculptor Mary Callery advised the de Menils: “If you want a house for $100,000, ask Mies van der Rohe; if you want one for $75,000, ask Philip Johnson.” Their understated modernist residence soon became the gathering place for Houston’s intellectual elite. Against all expectations, the couple transformed the deeply conservative Southern city into a thriving creative hub, forging lasting friendships with some of the most significant artists of their time.

An Encounter with the Avant-Garde

In 1965, John and Dominique hosted René Magritte at their home in River Oaks. Embracing the local culture, they took the Surrealist artist to a quintessentially Texan experience: the rodeo. Wearing a Stetson hat in true cowboy style, the Belgian painter seemed to thoroughly enjoy himself. When the de Menils later welcomed Andy Warhol and his New York entourage, they treated them to a shopping spree at Stelzig’s, a Houston institution since 1887, known for its saddlery, classic Western boots, and must-have cowboy jeans. That evening, the group dined at The Stables, a renowned downtown steakhouse.

In 1965, John and Dominique hosted René Magritte at their home in River Oaks. Embracing the local culture, they took the Surrealist artist to a quintessentially Texan experience: the rodeo.

Despite their refined, old-world manners, the de Menils had a deep affinity for the avant-garde and artistic experimentation. In the summer of 1967, John collaborated with Philip Johnson to stage what would become a landmark event in pop culture history.

Held in the garden of Johnson’s famed Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut, Museum Event #5 was an innovative performance featuring eight dancers from Merce Cunningham’s company. The conceptual music was composed by John Cage, costumes were designed by Robert Rauschenberg, and the artistic direction was entrusted to Jasper Johns.

As if that weren’t enough, the evening culminated in a concert by a then-little-known band backed by Andy Warhol: The Velvet Underground. On a stage set between the villa and the pool, Lou Reed, John Cale, and Nico performed what would later become rock classics—I’m Waiting for the Man and Venus in Furs. Among the fashionable crowd, Factory regulars like Paul Morrissey and Gerard Malanga could be spotted, dancing wildly. The night was a resounding success.

A Rising Influence in the Art World

Throughout the 1960s, the de Menils steadily expanded their influence in the art world. While John joined the board of directors at MoMA, Dominique leveraged her extensive network to carry out the couple’s ambitious patronage projects. For Double Vision, William Middleton was granted unprecedented access to the family’s private archives. He recounts: "One workday for Dominique, for example, a Friday in November 1964, when she was at their Manhattan town house, began at 7 a.m. with a phone conversation about upcoming exhibitions with the director of the Guimet Museum, in Paris. Midmorning, she had two calls: to a reporter at Newsweek who was planning to do a story on the arts scene in Houston, and to Diana Vreeland at Vogue, who was organizing a feature on the de Menils’ house in Houston, with its modernist architecture by Philip Johnson and its voluptuous interiors by Charles James. At midday, Dominique hosted a lunch at home, tête-à-tête, with Marlene Dietrich. Then, at 2:30 p.m., she went to Mark Rothko’s 69th Street studio to meet with the artist about his paintings for the chapel. The next day, she took the Schlumberger jet to Houston."

Despite their refined, old-world manners, the de Menils had a deep affinity for the avant-garde and artistic experimentation.

The de Menils also maintained strong ties in France. On June 1, 1971, they were invited to a dinner at the Élysée Palace by Georges and Claude Pompidou. That evening, the President of the Republic shared his vision for a new, accessible center for modern and contemporary art. "The project my husband presented that night aimed to offer everyone access to art in all its forms, within a single institution," Claude Pompidou later explained to William Middleton in a 2006 interview. "John de Menil was very, very enthusiastic and completely convinced. They promised to help us."

Though John passed away in 1973, Dominique remained deeply committed to the project. She played a crucial role in supporting Pontus Hultén—the first director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou—whom she had known since the 1960s, when he led Stockholm’s Moderna Museet.

Generous Patrons

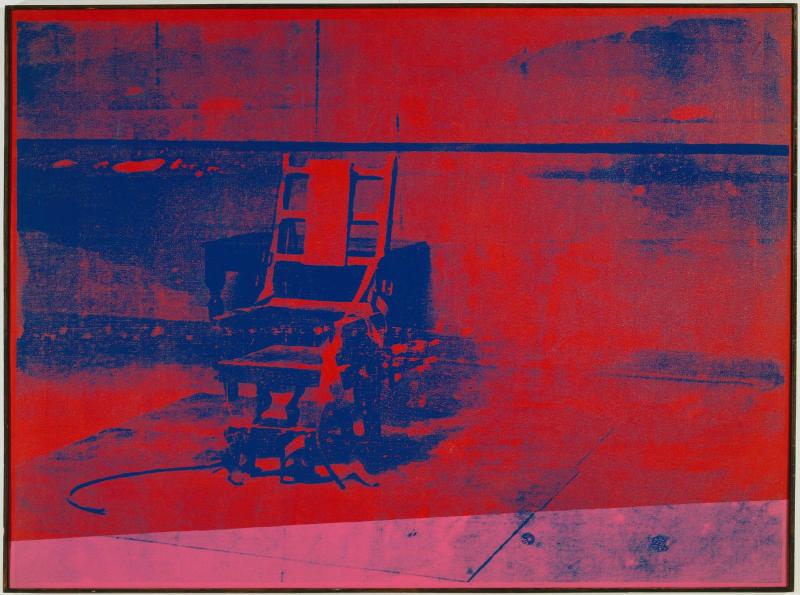

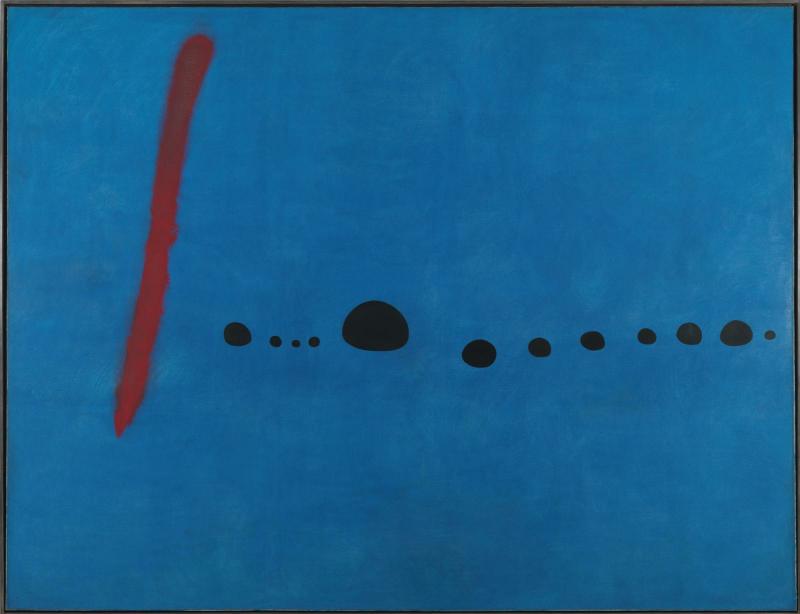

In 1976, Dominique de Menil and her children donated five major works to the Centre Pompidou—gifts of extraordinary significance. Among them was the magnificent Bleu II by Joan Miró (one of the three canvases in the series), The Deep by Jackson Pollock, Big Electric Chair by Andy Warhol, I Like Olympia in Black Face by Larry Rivers, and Ghost Drum Set by Claes Oldenburg. These were the first works by American artists to enter France’s national collection.

In 1976, Dominique de Menil and her children donated five major works to the Centre Pompidou—gifts of extraordinary significance.

The following year, in 1977—the year the Centre Pompidou opened—Dominique played a key role in founding the Beaubourg Foundation, now known as The American Friends of the Centre Pompidou. In 1980, the foundation evolved into the Georges Pompidou Art and Culture Foundation, led by its president, Sylvie Boissonnas (Dominique’s sister). Under her leadership, the foundation donated several landmark works to the museum, including Thira by Brice Marden, "monument" for V. Tatlin by Dan Flavin, and Untitled by Donald Judd. To this day, the American Friends continue to collaborate closely with the Amis du Centre Pompidou association.

In 1984, a major exhibition titled Donations from the de Menil Family showcased some of the exceptional works that the de Menils had gifted to the Musée National d’Art Moderne.

On December 31, 1997, Dominique de Menil passed away, after more than seven decades devoted to her passion for art and artists. ◼

Related articles

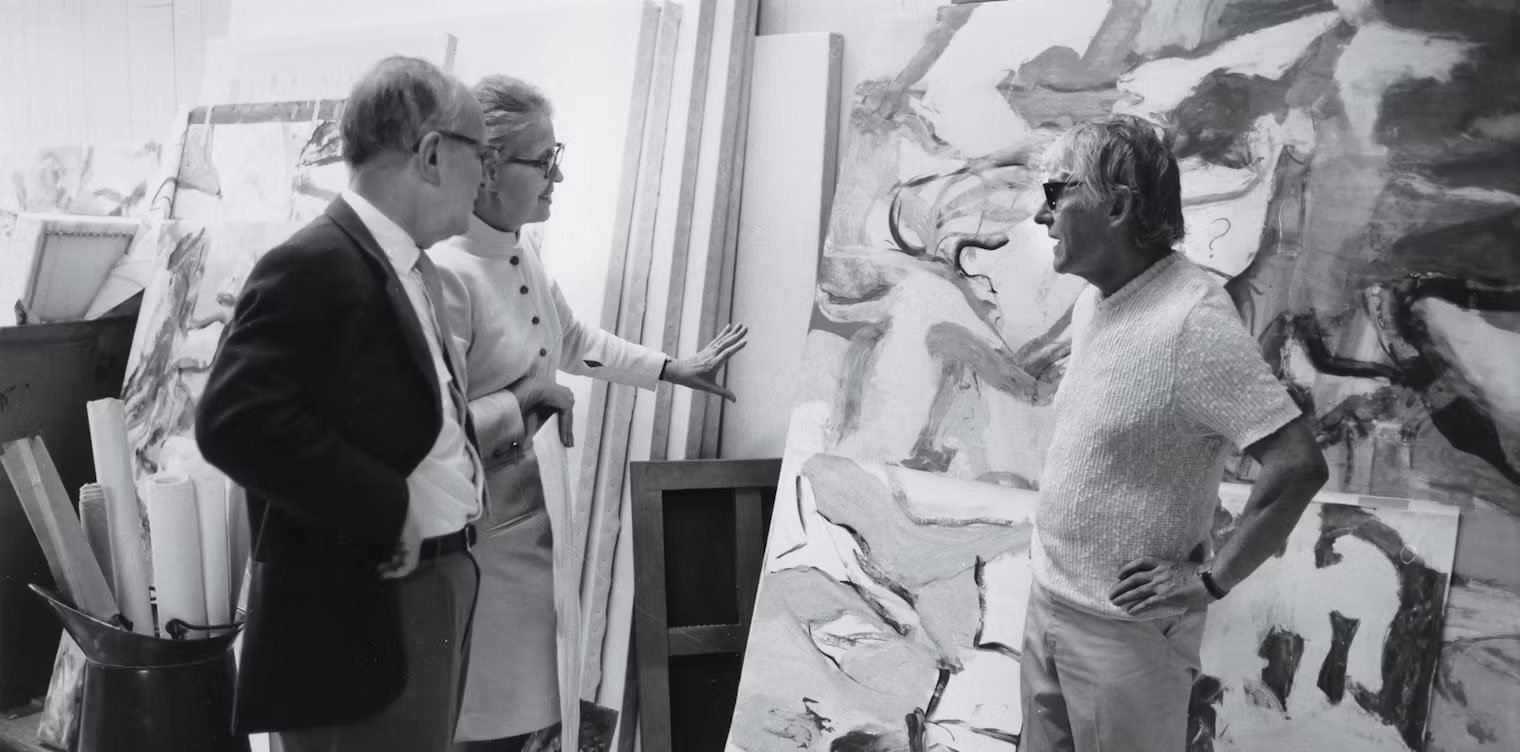

John et Dominique de Menil en visite dans l'atelier de l'artiste Willem de Kooning à Long Island, 1970.

Photo © Adelaide de Menil

Courtesy of Menil Archives/The Menil Collection, Houston