From Pompidou to "Beaubourg": the secret history of Renzo Piano's and Richard Rogers's architectural project

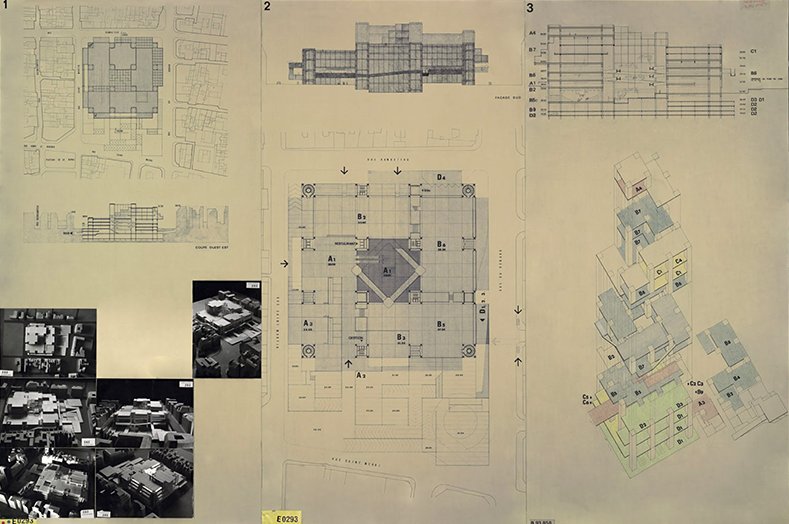

"Project 493": this is the (unofficial) code name that was first used to identify Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers's project. In fact, 493 was their submission package number — one of the hundreds sent to the jury made up of eminent personalities, including architect and designer Jean Prouvé and architects Oscar Niemeyer and Philip Johnson. The goal of this international competition at the instigation of Georges Pompidou? To imagine the future cultural heart of Paris, a place "that would be both a museum and a centre for creation where the visual arts would go hand in hand with music, film, books and audiovisual research", as announced by the French President in Le Monde in October 1972. In all, a total of 681 dossiers were sent to the jury – contributions came from all over the world, from Argentina to Japan and the United States. The rules were fairly simple: candidates had to present an innovative vision in a series of drawings, and develop the whole project in a six-page descriptive dossier. The project had to be presented on a single plate of the following dimensions: 2.40 x 1.80 m. Renzo Piano answered the telephone on 16 July 1971: they'd won!

Project 493": this is the (unofficial) code name that was first used to identify Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers's project. In fact, 493 was their submission package number — one of the hundreds sent to the jury made up of eminent personalities, including architect and designer Jean Prouvé and architects Oscar Niemeyer and Philip Johnson.

In an interview in the book Centre Pompidou, Piano + Rogers, he looks back with humour: "My level of French at the time was that of a schoolboy, moreover, the level of a schoolboy who was always clowning about at school. The person asked me if I was Mr Piano, and on my confirmation of this fact, announced that we were "lauréats". I replied that it was obvious that we were architecture graduates, otherwise it was evident that we couldn't practice this profession. So the poor little woman had to repeat to me for several minutes that we were laureates, until I finally understood that that meant we had won the competition. At which point, I collapsed into my seat and called Richard in London. We were the unanimous winners." To think they almost didn’t take part…

Boris Hamzeian, researcher and architect, investigated for almost five years in order to understand the origin of the Centre Pompidou. He combed through the Archives nationales in Paris, those of Richard Rogers's old firm and those of the Ove Arup & Partners engineering and consultancy firm in London. A thesis grew out of the thousands of pages consulted and annotated, then an erudite book, published in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou, 1968-1971, Live Centre of Information, from Pompidou to Beaubourg. He recounts: "It all began in late December 1970. Richard Rogers and his wife Su Rogers, also an architect, had a firm in London. Through Ted Happold, an engineer who was working for Ove Arup & Partners at the time, one of the largest engineering and consultancy firms in the English-speaking world, the couple discovered the existence of the competition. Happold was obsessed: he wanted a complex structure that would use cast steel, an avant-garde technique at the time – but in order to get the project up and running, he needed architects. He knew Richard and Su well". At the time, the Rogers worked regularly with their friend, Renzo Piano (Piano joined Rogers in London in 1971 to set up their Piano & Rogers architecture firm, editor's note). So they involved the Italian in the adventure, as well as another Genoese architect, Gianfranco Franchini, with whom Piano had already worked. The team was established.

It all began in late December 1970. Richard Rogers and his wife Su Rogers, also an architect, had a firm in London. Through Ted Happold, an engineer who was working for Ove Arup & Partners at the time, one of the largest engineering and consultancy firms in the English-speaking world, the couple discovered the existence of the competition.

Boris Hamzeian, researcher

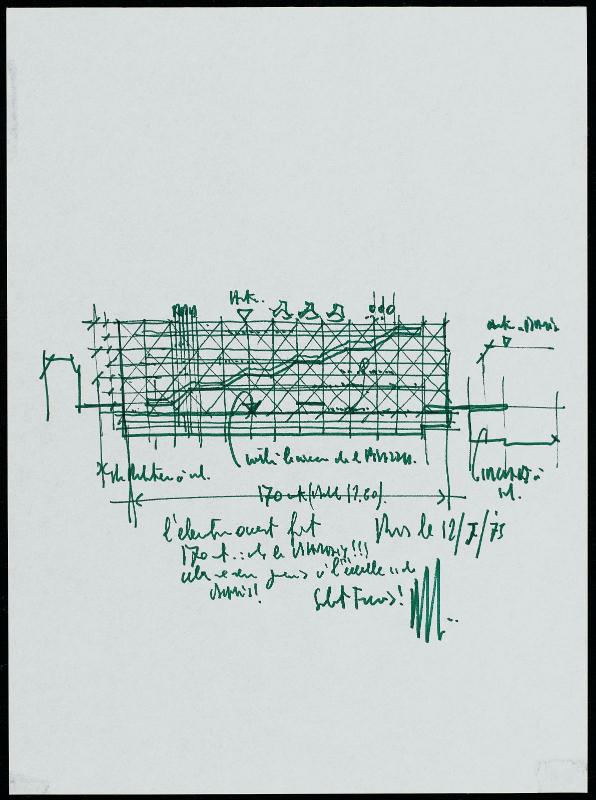

They set to work in their premises at 32 Aybrook Street, in the Marylebone district. Renzo Piano recalls: "We worked on the competition mostly in the evenings and at night. It's always like that when you have no work, in fact you work flat out. I remember we had pasted one of my sketches to a window, continuing to build it up with elements, ideas and proposals. The window overlooked the small park in Aybrook street. It was pleasant to work on this semi-transparent sheet, through which we could see the greenery. This sketch was one of the foundational drawings for the final competition project. But in January 1971, a bombshell landed: Richard Rogers changed his mind. He wrote down his reservations in a letter addressed to his comrades. Boris Hamzeian recounts: "If Rogers hesitated, it was because the firm was already working on another museum for Glasgow city, and he felt much more confident about this project. He also feared that, even if they won, their future cultural centre would never be built because the terms of the competition suggested that this might be a possibility… And Rogers was against this idea of centralising culture in a single place. He saw that it as a product of the power of the French right." With his comrade Piano, Rogers was in fact a pure product of the libertarian ethos of the 1970s. Richard Rogers: "I didn't like the idea that the client was a President. It scared me. Of course I nurtured a distrust of power." (in Centre Pompidou, Piano + Rogers). He may also have hesitated for personal reasons: he was breaking up with his wife Su (who finally did not participate actively in the competition).

However, the fact remains that after this prevarication, Rogers, Piano, Franchini, Happold (and a few trainees) got back to work and completed the project in a little more than a month. The team worked until the last minute on 28 June 1971, the deadline. If Richard Rogers is to be believed, "at a quarter to midnight, we still hadn't finished". Their collaborator, Marco Goldschmied, rushed to the central post office in London just before closing time. Alas! Once he arrived, he realised that the drawings would not fit in the tube provided by the postal services. So he set to work trimming the plates on the ground, on the pavement. But three days later, the tube was returned to sender due to "insufficient postage". Renzo Piano: "We panicked. By then the deadline was behind us. We had a disjointed exchange with a post office employee who found a solution. We had to send the mail again and therefore to stamp it again, but we managed to make the date illegible. This also gives you an idea of the relative importance we attached to the competition. It was one thing among so many others that we were doing at the time and we took it on in a very casual manner."

When Piano and Rogers called the French authorities to find out whether the famous missive had actually been received, they were informed that it had not. The English postal services were paralysed by a strike, and all projects coming from Great Britain had been disqualified.

But that wasn't the end of their setbacks. When Piano and Rogers called the French authorities to find out whether the famous missive had actually been received, they were informed that it had not. The English postal services were paralysed by a strike, and all projects coming from Great Britain had been disqualified. At their first meeting, the jury nevertheless decided unanimously to allow them to compete after all. As Boris Hamzeian sums it up: "Theoretically, the winning project should not even have participated!"

While searching through the RSHP (ex Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners) archives in London in 2017, Boris Hamzeian discovered the very first known sketches of what would become the Centre Pompidou. Hastily sketched with an orange felt-tip, we see the distinctive signs of the building: a space for pedestrian circulation (the future "Piazza"), mobile levels, etc. The project also included a tunnel that was supposed to link the building to the network of the Les Halles metro station – an idea that was later abandoned. On the sketches we also discover that the original project, known as "Live Centre of Information", included multiple screens on the façade. Boris Hamzeian: "It's an idea that came to nothing, but to my mind, it was the best idea in the project. Piano and Rogers wanted to project images from all over the world on these electronic screens in order to inform the crowd gathered on the Piazza." Another of the architects' ideas: equipping the top of the building with a satellite in order to communicate with other identical centres – as in a connected hub. "A sort of Internet before the Internet! Boris Hamzeian enthuses. In 1971 it was totally avant-garde."

Another of the architects' ideas: equipping the top of the building with a satellite in order to communicate with other identical centres – as in a connected hub. "A sort of Internet before the Internet! Boris Hamzeian enthuses. In 1971 it was totally avant-garde."

We also discover other candidates' projects in his book, such as those of Rem Koolhaas, André Bruyère, Paul Chemetov and the Archigram collective. Some are futuristic (even fantastical) and many propose towers, some with more than fifty floors – which was totally allowed by the competition. At the time, the rule for Paris city centre was not to exceed a height of twenty-eight metres. But Pompidou introduced a special dispensation for the competition. The president was interested in the major trends of international architecture and wanted to bring new life to French architecture, which he considered too conservative. Boris Hamzeian: "Pompidou appreciated people like Bernard Zehrfuss, who designed the UNESCO building, inaugurated by the president himself in 1970, and Guillaume Gilet, to whom we owe the Palais de Congrès at the Porte Maillot, notably (1975, editor's note), and Fernand Pouillon, responsible for the reconstruction of the Vieux-Port in Marseille after the war." And for him, the idea of modernity was synonymous with verticality. Already, in January 1968, when he was Prime Minister under De Gaulle, Pompidou launched the idea of a tower on the Beaubourg plateau. In it he wanted to house the Ministry for the Economy and Finance. But the maelstrom of May 68 came along and swept away the project for the "Pompidou Tower". On his return to office in June 1969, but this time as Head of State, he reactivated his idea of a tower in the heart of Paris. But to mark a break with his predecessor, he decided to dedicate his monument to culture.

He too hesitated. The researcher recounts that "After three days of selection, and with only three submission packages remaining, Jean Prouvé proposed starting all over again! Prouvé was preoccupied at the time by the construction works for Les Halles (which grouped a new commercial centre and the métro). He thought that by agreeing to preside over this competition he could influence the jury and apply pressure to preserve Baltard's historic metal pavilions, which were about to be destroyed (they were destroyed in August 1971 in order to enable the construction of the RER station and the Forum des Halles, editor's note)." Prouvé hoped to find a project that would recycle the pavilions. Unfortunately, he failed to convince his comrades on the jury.

History recounts that the project presented by Piano, Rogers and their team was the unanimous winner – in reality, it won by eight votes to one. In addition, by combing through the archives, Boris Hamzeian discovered that Jean Prouvé, the president of the jury, was not the ardent defender of project 493 he was reported to be.

Between 12 and 13 July 1971, the staff of Robert Bordaz (in charge of the competition and future first president of the Centre Pompidou), presented finalist project 493 to the French President. That same evening, Georges Pompidou and his wife Claude went secretly to the Grand Palais, where the projects had been presented to the general public since June. They wanted to be clear in their own minds. "Georges Pompidou knew everything, he was the one who made the choice", Boris Hamzeian, remarks. The jury entered its final deliberation phase on 14 July. The name of the winners was finally revealed in the Grand Palais on 19 July. And nothing went according to plan. Renzo Piano: "I recited the acceptance speech which I had learned by heart. Unfortunately, the public started screaming almost immediately. They were shouting: "Go away! Shame on you, a refinery in the heart of Paris!" I didn't know how to respond to them, so I continued my acceptance speech "Ladies and Gentlemen, thank you very much", as the cries of indignation became increasingly pressing and aggressive. It was unforgettable. Imperturbable, I continued my acceptance speech for fifteen minutes while the crowd threw tomatoes at us until the end." The rest is history.◼

* 1968-1971, Live Centre of Information, from Pompidou to Beaubourg, Actar Publishers, in collaboration with Centre Pompidou