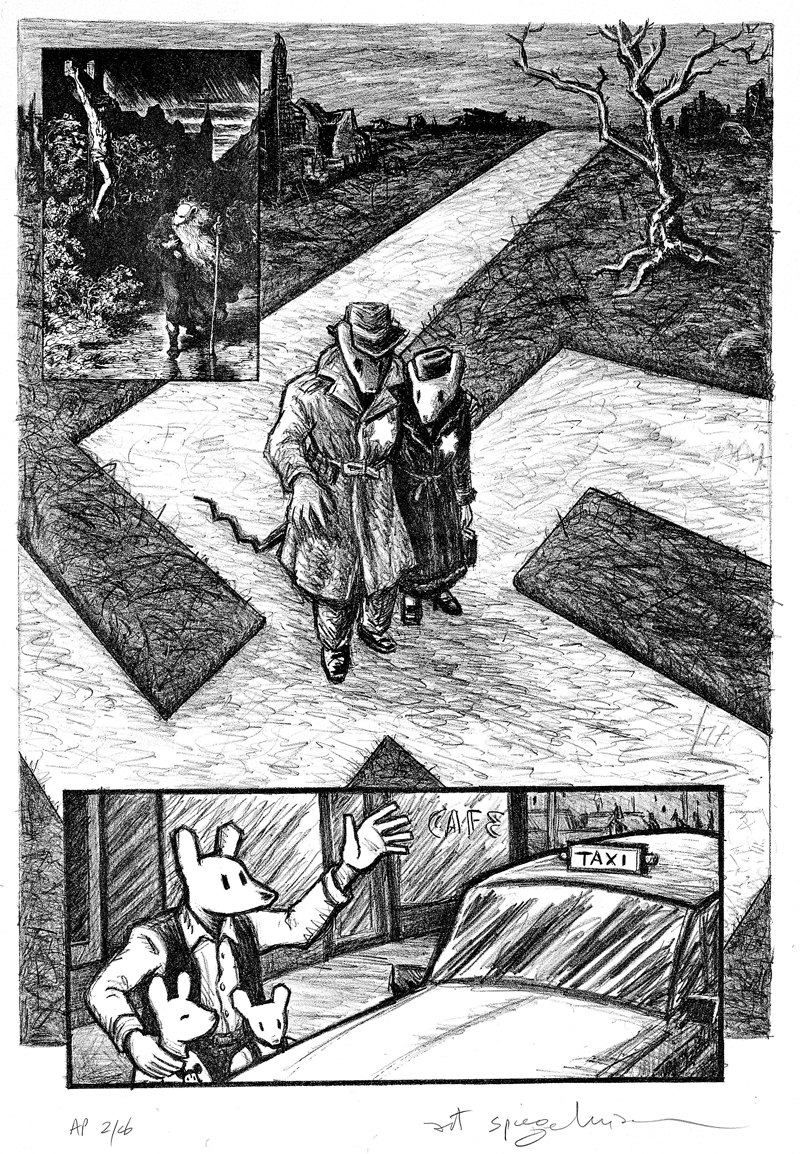

Art Spiegelman: “It’s the formal aspect of the work which nurtures all my comic strips.”

Art Spiegelman is an exacting perfectionist: his pictures and the way he translates the story into boards reveal a sense for composition that leaves nothing to chance. As a radical author boasting a proteiform style, this comic strip history buff has always managed to adapt the form of his drawings to the pithiness of his prose. He has embraced autobiography, deploying great integrity, showing that the blending of prose and pictures peculiar to comic strip makes it a medium in its own right rather than a sub-genre, expressing the most intimate of introspections, on a par with literature, the fine arts and film. In his capacities as a comic strip author, illustrator, editor and critic, Art Spiegelman has long shattered the frontiers which appear to separate high-brow culture from pop culture.

Spiegelman has produced both short comic strip stories and cartoons published in underground magazines and the mainstream media, as well as illustrations for the press and the world of publishing. In his monumental graphic novel Maus (published from 1980 to 1991), Spiegelman tells the story of his parents who escaped from Auschwitz. He drew the Jews as mice and the Nazis as cats. According to essayist Benoît Peeters, his work helped people identify with reality in a far less indecent way than through a film about the Holocaust. When MetaMaus was released in 2012, the Bibliothèque Publique d’Information held an exhibition. Interview.

Benoît Mouchart — Twenty years after Maus, you published MetaMaus. Was this a necessary stepping stone in order to move onto new projects ?

Art Spiegelman — Since Mauswas published, I’ve been chased by thousands of mice. I’m proud of my work, but I can get exasperated with its success. All that I have worked on since, in a spirit of reinvention, is overshadowed by this tragic work. So I’m hoping that MetaMauswill answer all the questions that Mausraised, so I can at last turn the page. When someone asks me “But why mice ?”, I’ll tell them “Read pages 110 to 119 !” The book still haunts me. I hadn’t realised this, until I started looking at photos, documents, sketches and notes to produce MetaMaus. Those who think it was cathartic to work on Maushave got it wrong. I had to grow a shell in which to work so that I wouldn’t get hurt. The armour disappeared when I finished the work […]. Facing up to this past and family tragedy showed me that the wounds are still gaping.

Those who think it was cathartic to work on Maushave got it wrong. I had to grow a shell in which to work so that I wouldn’t get hurt.

Art Spiegelman

Your work as a young adult was tied in with counterculture in the 1970s and autobiography. Is your inspiration both personal and, above all, political ?

Art Spiegelman — It’s the formal aspect of the work which nurtures all my comic strips, whether inspired by my personal life, political affairs or whatever. The words and pictures on the page, like a diagram, a circuit of thoughts.

You have quoted Marshall McLuhan : “When a medium loses its authority in a culture, it becomes an art form, or it dies.” Do you think this exhibition can help achieve recognition for comic strips ?

Art Spiegelman — Of course. There are many comic strip events, in Europe and in the US. We will soon have to be wary of comic strips as they go more mainstream. Part of the energy in this medium comes from its popular roots, and I hope to help preserve this tradition. After all, I have created the Garbage Pail Kids, comic strips for Playboy, and this graphic novel which won the Pulitzer Prize. ◼

Texte initialement paru dans le Code Couleur 12 à l'occasion de l'exposition « Art Spiegelman, co-mix » (21 mars-21 mai 2012) à la Bibliothèque publique d'information.

Related articles

In the calendar

© Art Spiegelman