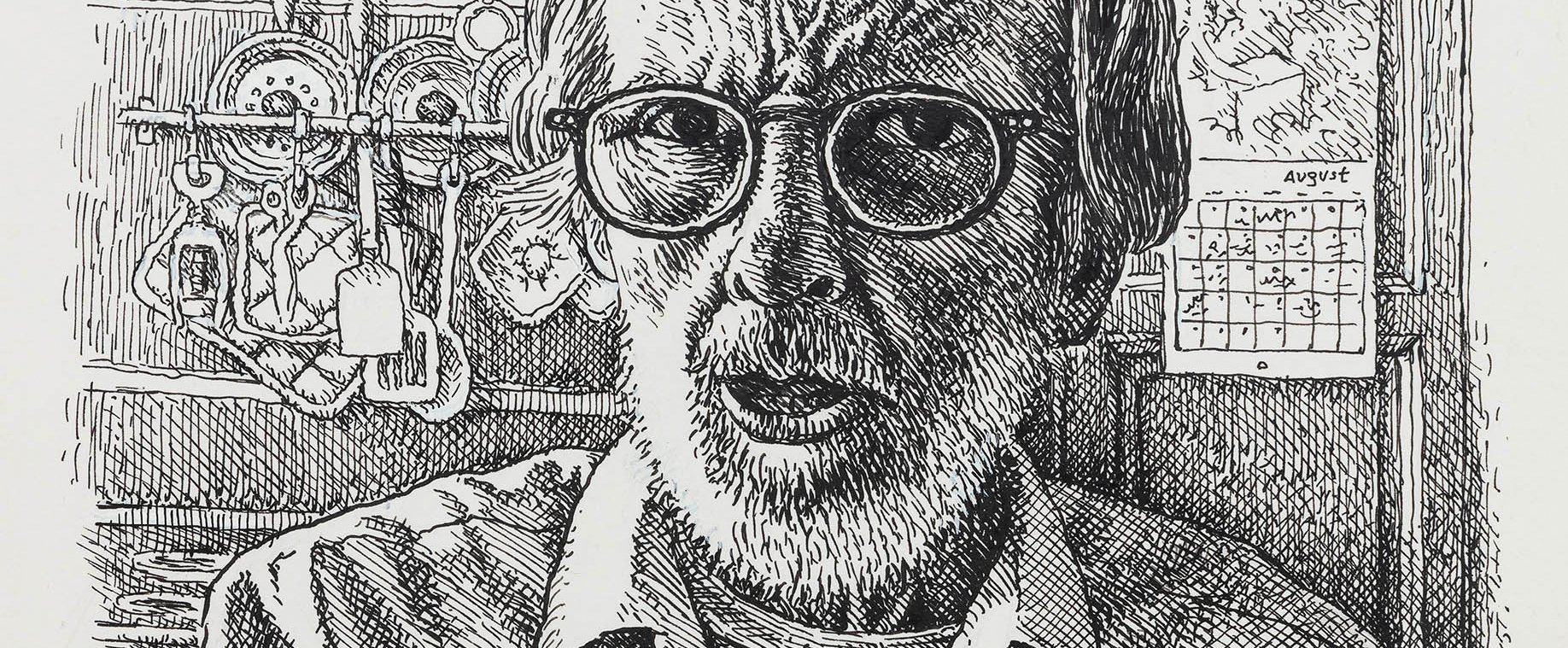

Robert Crumb : 'Comics are hard work for very little reward.'

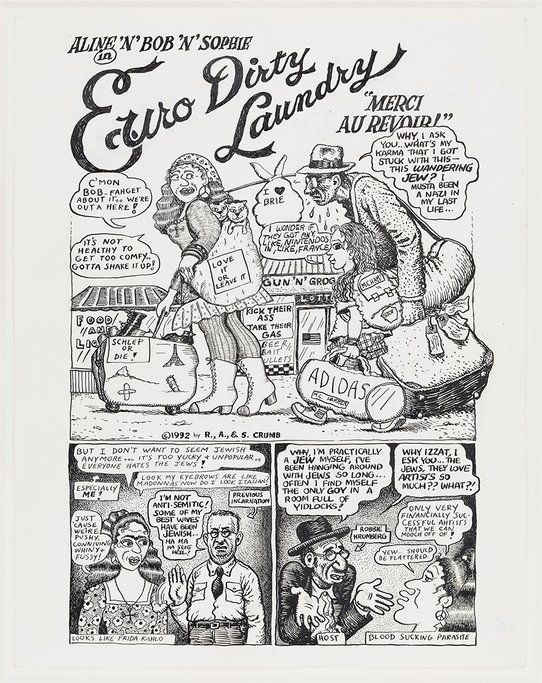

The French department of Gard is known for its Roman ruins, its landscape covered in scrubland, its Provençal villages, and… the cartoonist Robert Crumb, best-known as R. Crumb. This rugged but picturesque setting, once used as a place of hiding by members of the Resistance, has for years been home to a hero of American counterculture. In 1991, Crumb, who was born in 1943 in Philadelphia, and went on to become one of the greatest cartoonists of the last 50 years, decided to settle down in a medieval village in the south of France. He never left and seems to feel right at home. He would say himself that he has no complaints – apart, perhaps, from the fact that when the phone rings, it’s usually someone from the French water company, SUEZ. ‘I’m in a fight with them over the bill. They are demanding €4,500!’ This is how the interview with Crumb starts: with the phone ringing at exactly the moment he starts answering our questions, and already his characteristic narrative skill starts to shine through. All of the ingredients are there: the humor of the situation, the picaresque tone, the biting self-deprecation, and the absurdity of the everyday.

My wife Aline was a very strong-willed woman, a force of nature. She managed my life. Now that she’s gone [Aline died in November 2022], I don’t know what to do. I’m a little boy who has lost his mommy.

Robert Crumb

In his comics too, like Fritz the Cat (1965–72), and with the character Mr. Natural, Crumb uses personal anecdotes as starting points for his fables. They are anything but moral, looking at the world from the point of view of the outsider, the foreigner, the court jester. Back in the real world, it’s Crumb vs. SUEZ, the beleaguered expat against Kafkaesque French bureaucracy: ‘They say I must have a leak somewhere in my water pipes. I cannot answer this young woman in French. I gave up, said, “désolé,” and hung up.’ He describes how his second wife Aline Kominsky-Crumb was the one who pushed for them to move to France. ‘She fell in love with France in the 1980s. She engineered the whole thing. I passively went along with it.’ David Zwirner gallery, which represents him, mounted the exhibition ‘Sauve qui peut! (Run for Your Life)’ in early 2022, recounting part of this family story. The exhibition showed the drawings and storyboards of Crumb, Kominsky-Crumb, and their daughter, Sophie Crumb, side by side. ‘She was a very strong-willed woman, a force of nature. She managed my life. Now that she’s gone [Aline died in November 2022], I don’t know what to do. She would have dealt with frickin’ SUEZ. I’m a little boy who has lost his mommy. That’s the pathetic truth of the matter.’

Crumb’s ideas come to him like those unfortunate SUEZ calls – suddenly, unexpectedly. There’s no transcendental moment of inspiration, certainly no abstract concepts. It’s the world’s raw material expressing itself – this awful, dirty, nasty reality, with its moral shackles and other devious stereotypes. Perhaps the best way to defy convention is to laugh at it. It’s a question of subjectivity: ‘Real inspiration comes from the subconscious mind,’ he insists. ‘It has to go as directly as possible from the subconscious to the hand, the pen, the brush, the blank surface, the paper, the canvas.’ When asked about how he – the enfant terrible of America’s hippy years – sees his adoption by the art world, he retorts, ‘Mostly, these art world people are oblivious to the graphic arts, work done for print. Generally, they know nothing of its history except for [Honoré] Daumier and maybe Gustave Doré.’ Then he adds, ‘I have no idea how the fine art people view my comics.’

Real inspiration comes from the subconscious mind. It has to go as directly as possible from the subconscious to the hand, the pen, the brush, the blank surface, the paper, the canvas.

Robert Crumb

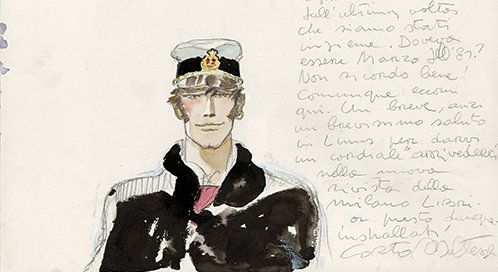

That may be true, but the world of fine art has well and truly given him its stamp of approval. In France, Crumb is one of the few artists to have made the leap from the page to the gallery. Nowadays, graphic arts in general are inspiring young artists like never before: you just have to see manga’s popularity with Gen Z, in particular among emerging artists like Neïla Czermak Ichti and Ibrahim Meïté Sikely. Yet this broadening of visual art genres owes a lot to pioneers who jumped into the spot left by Pop Art and made a porous border between fine arts and what Lucky Luke creator Morris called the ‘ninth art’. In the 1970s, it was through magazine covers that the French public discovered Crumb and his famous ‘scratchy line,’ as well as his world of portly fishwives accompanied by their nerdy, bespectacled husbands. In 2012, the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris organized the first museum retrospective of Crumb’s career.In the meantime, the museum world has broadened its horizons. Increasingly, the distinction between ‘noble’ arts and popular arts is a thing of the past. In 2009, Maison Rouge in Paris was already combining the two in its exhibition ‘VRAOUM!’ It was the start of a new trend that stuck – quantifiable by the number of graphic artists represented by French galleries such as Galerie Anne Barrault (Jochen Gerner, Roland Topor, and Killoffer), Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois (Winshluss), and Galerie Catherine Putman (Frédéric Poincelet).

Robert Crumb is still Robert Crumb, the man who fights the powers that be and criticizes big money. That said, he is aware of his role as a link between the two. ‘I, too, live off the privileged elite,’ he concedes. ‘You might even go so far as to say I’ve become one of them. Ironic, huh?’ When asked how his work has changed over five decades, he ventures, ‘I guess you could say that I and a lot of other contemporary comics artists have used this popular commercial medium to make fine art, that is, to do personal self-expression, as has been done in the fine art world. We turned comics into “fine art.”’ Crumb, whose work is now collected by some of the most important museums in the world, evades the question when we ask him the secret of his success. ‘I did nothing to make it happen. I did not hustle the fine art galleries.’

Comics are hard work for very little reward. You have to love it for its own sake to keep doing it. You’re not going to make much money, if any, no matter how good it is. This harsh reality does help to keep the medium relatively authentic.

Robert Crumb

He also takes the opportunity to reaffirm his unshakeable attachment to comics: ‘I do still love the medium and am curious about what sort of comics are being published these days. There are a lot of pretentious, tedious graphic novels coming out, but among them there are also some quite excellent books, some by very young artists still in their 20s.’ He spontaneously mentions the Zurich-based artist Simone F. Baumann, adding, ‘Some of the best comics are being done by women nowadays.’ In the background, however, the difficult reality of earning a living in comics endures. Crumb thinks of himself as lucky but stands in solidarity with the ‘99%’ of comic book artists who ‘cannot HOPE to earn a living from their comics work.’ When talking about his medium, he gets serious: ‘Comics are hard work for very little reward. You have to love it for its own sake to keep doing it. You’re not going to make much money, if any, no matter how good it is. This harsh reality does help to keep the medium relatively authentic.’ ◼

Editorial partnership Art Basel Paris × Centre Pompidou

Original publication to be found here

Related articles

In the calendar

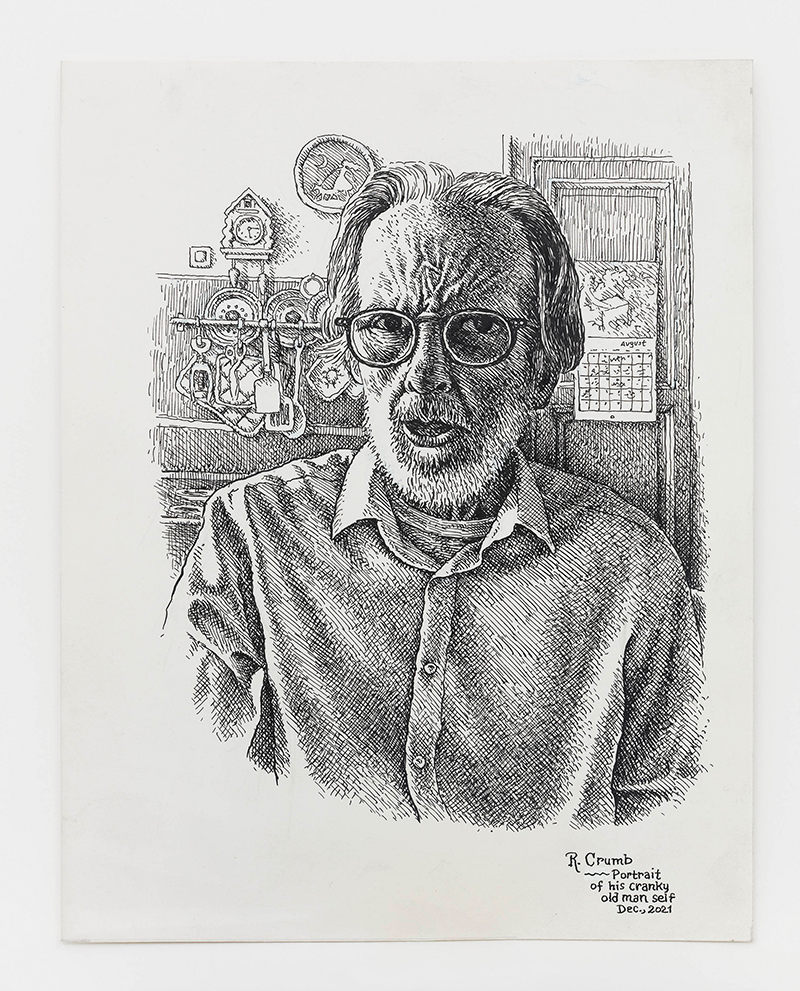

Portrait of His Cranky Old Man Self, 2021 © Robert Crumb, 2021.

Courstesy of the artist, Paul Morris and David Zwirner.