Exhibition

Pierre Paulin

11 May - 22 Aug 2016

11 May - 22 Aug 2016

The event is over

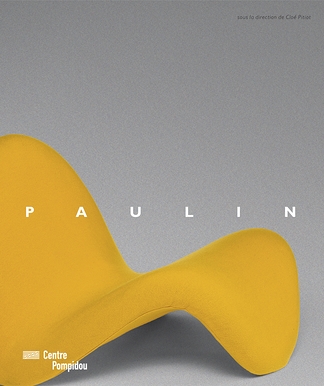

Designer, architecte d’intérieur, créateur, Pierre Paulin sculpte l’espace, l’aménage, le « paysage ». Ses environnements, ses meubles, ses objets industriels, se mettent au service du corps. Avec plus de soixante-dix pièces de mobilier et une cinquantaine de dessins inédits, l'exposition consacrée par le Centre Pompidou à Pierre Paulin propose une traversée de tout l’oeuvre du designer et de quarante années de création. Elle présente des pièces phares devenues des « icônes » de l’histoire du design - Anneau, Mushroom, Ribbon Chair, Butterfly, Tulip... - et fait la part belle à des projets inédits, auto-édités, comme le Tapis-siège, la déclive, la tente, etc. Des pièces rares des années 1950 et des prototypes sont également dévoilés dans l'exposition.

En 1971, Pierre Paulin est choisi par Claude et Georges Pompidou pour revisiter l’aménagement des appartements privés du Palais de l’Elysée. En 1984, c’est au même designer que fait également appel François Mitterrand pour concevoir l’architecture intérieure et le design de son bureau présidentiel.

L’exposition invite le visiteur à établir un dialogue entre corps et confort. Parce que les recherches de Pierre Paulin ont été sans cesse motivées par les thèmes du confort et d’un nouvel art de vivre -au ras du sol par exemple, le parcours propose au public de s’asseoir dans les sièges les plus emblématiques du créateur, des rééditions mises à la disposition des visiteurs.

L’exposition présente, enfin, une reconstitution inédite du living room de la Calmette, la villa dessinée dans les Cévennes par le designer dans les années 1990 : le public y expérimente un épais diwan (tapis) glissant le long d’un mur, se retournant sur le sol et accueillant quatre fauteuils Tongue.

"Extra-Paulin", by Cloé Pitiot

In his fifty-year career, Pierre Paulin transformed seating, reinvented spatial design and founded the first global design agency in France. Through a hundred or so exhibits – furniture, environments, projects and drawings – the Centre Pompidou’s retrospective offers an unprecedented overview of his work from 1950 to the 1990s.

HIS WORK LOOKS AS MUCH AT HOME IN THE WORLD OF JAMES BOND AS IT DOES IN THE ÉLYSÉE PALACE

Pierre Paulin designed for everyone, and his work looks as much at home in the world of James Bond as it does in the Élysée Palace. His opposing qualities, “simplicity of line, austerity, an attraction to a somewhat ascetic conception of utopia, but also energy, vitality, humanity, playfulness, a sensuality all the more developed for being so often disguised … all these found in his art a terrain of peaceful coexistence”, his friend Alain Gheerbrant wrote in 1983. Testimony to his eclectic energies, his production was among the most prolific of any 20th century designer’s. If he had a gift for capturing the mood of the age, his real talent was for anticipating it.

Paulin graduated from the Centre d’Art et de Techniques (today’s École Camondo) in 1950. Trained there in the tradition of French furniture design, he began his career with Marcel Gascoin, where he picked up the rudiments of modernism: “In my early days at Marcel Gascoin’s, we were very much influenced by modern Swedish design, by their products for young families. I was 25, I was interested in well-made pieces at reasonable prices,” Paulin recalled in a 2007 documentary. In July 1951, he went off to discover Scandinavia himself. Nordic architecture and design, and notably the work of Alvar Aalto, would have a decisive impact on his development. He read the magazine Interiors, where the new culture of design was represented by the work of Charles and Ray Eames, George Nelson, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertois and others. Looking now for a free hand and efficiency of production, Paulin offered his work to a number of manufacturers: A. Polak Originals, Meubles TV, Thonet France. For A. Polak Originals, he created his famous Anneau chair, selected for the 11th Milan Triennale: “I took two broom handles, leaned them against the wall, and using kraft paper, I made a circular band, which would be done in leather, and that was it! Then I had to find a frame that would support it all: two rectangles of bent steel [tube], held together by four fasteners. The chair was simple, like a sack.” At Meubles TV, Paulin found sympathy for his own functional and modernist aspirations, a passion for line and proportion, for formal rigour. With Thonet France, he drew on the idea of the range developed by American manufacturers, proposing a line of office chairs and other contract furniture united by a new and distinctive grammar. He reflected on the structure of the chair, even questioning the use of traditional upholstery fabric: in 1957, he and Thonet took out a first patent for the use of stretch materials.

It was in Paris in 1958 that Paulin met the designer Kho Liang Ie, then artistic director at Artifort, and the firm’s managing director Harry Wagemans: their enthusiastic collaboration would result in an avant-garde design like no other. Paulin’s researches on stretch covers took a decisive step forward as early attempts using swimsuit fabric proved promising. The principle of the one-piece, solid colour, seamless stretch cover revolutionised the very way one thought of a chair. Now covers could be removed, washed and exchanged according to mood, whim or season. With his idea of cover as swimsuit, Paulin completely rejuvenated the idea of the chair, radically simplifying its lines and so reorganising its structure that the frame disappeared behind the stretch cover to leave pure form. Chairs became chromatic punctuations. An example is the famous Mushroom chair – “the best piece I ever designed, industrially speaking. Could it be done any more economically? There’s only one fabric, the [stretch] material. Three metal circles … and four rods joining them together. Then you put on its ‘swimsuit’ and your done!”

PAULIN COMPLETELY REJUVENATED THE IDEA OF THE CHAIR, RADICALLY SIMPLIFYING ITS LINES AND SO REORGANISING ITS STRUCTURE THAT THE FRAME DISAPPEARED BEHIND THE STRETCH COVER TO LEAVE PURE FORM

At the height of his success as a designer, Paulin confided: “I’ve always been honest in my work. In fact, I wanted to be an architect.” In this respect, he was self-taught, moving on from interior to interior, from commercial stand to commercial stand. His space designs were based on three principles: the creation of tension (curves of nature / sharp edges of industry, softness of lightweight materials / rigidity of the supporting structure), reversal (ceiling treatments becoming floor treatments, and vice versa) and punctuation by means of colourful mobile elements.

In 1969, President Georges Pompidou’s commission for the renovation of the private apartments at the Élysée brought together Paulin’s work on mobile and removable architectures (such as the tent or igloo) and his experiments with ceilings. Paulin thus created a kind of tent cathedral, combining principles of church architecture, with its intersecting ogives, with the new materials of the 1970s. The stone of the church was replaced by prefabricated plastic modules, while the windows shattered into choirs of glass rods. The project marked the beginning of a new line of exploration for Paulin: having designed individual objects and shaped interior spaces, he now sought to draw the processes together. In 1972, he developed his idea of integrated design, exemplified in a modular interior. This ambitious project was rejected, but it had set him on the path to global design, the design of space and its contents, the integration of design, production, distribution and marketing.

When he set up ADSA, in 1975, with Maïa Wodzislawska and Marc Lebailly, Paulin adopted a new approach, centred on the notions of industrial and global design, which saw designers work closely with manufacturers throughout the process. Inspired by experiences in America, Paulin chose to work through a team: “I’m the expert the project leaders consult, the overall manager, and in principle the designer of most of the products developed here, but I’m no longer the only one involved.” Now distanced from both immediate creative activity and the object under development, Paulin found himself hankering for sole responsibility for a project from beginning to end. He would often break out from the team to take up his place at the drawing board, reworking and refining the basics of his ranges. When François Mitterrand asked him to refurbish his presidential office in 1984, he came up with a theatrical design, part innovation, part return to classicism. One might wonder what impelled his revival of interest in traditional construction; he said himself that it was from then on that he sought to accord to hand work the importance it deserved. In his work with the Atelier de Recherche et de Création (the research and design section of the Mobilier National, the French national furniture collection and government furniture agency) – on the Table Cathédrale, the Siège Curule, the Chaise à Palmette – Paulin drew as much on the Gothic as on the Antique or on traditional Asian furniture. Three decades ahead of his time, already in the early 1980s he was turning back to slow production.

Taking time in thinking, in making. Choosing the material, touching it, transforming it through the well-honed skill of the hand. Paulin returned to fundamentals, the object was the thing, once again a self-sufficient project. In 1995 he left ADSA to move to the Cévennes, where, at La Calmette, he built a house of mountain stone, laying out the spaces of his new life. This was his first architectural project, the summation of fifty years of exploration in design: “I’m not at all an authority, a guru. I’m a follower. The individual is nothing, it’s the product that counts. People shouldn’t be interested in the designer. If people think of me as a guru, they’re completely wrong. I was the disciple of no-one, and I have none of my own.”

Cloé Pitiot

Source :

in Code Couleur, n°25, may-august 2016, pp. 16-21

Where

Galerie 3

When

11 May - 22 Aug 2016

11am - 9pm, every days except tuesdaysPartners