Marlène Huissoud, artist-designer of the living world: "My client is the insect."

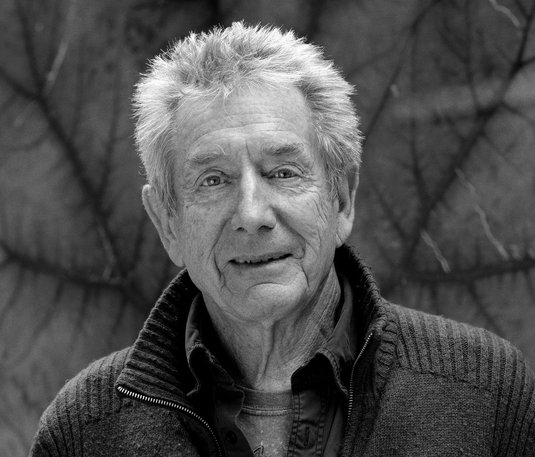

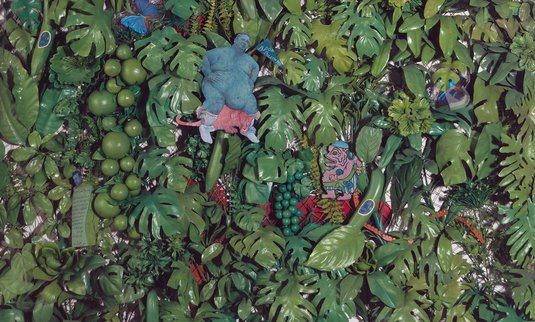

For Marlène Huissoud, born in 1990, everything began in the Alps of Haute-Savoie, in Lossy, a small village on the southern slopes of the Voirons. Her father was a beekeeper, her grandparents and great-grandparents were farmers, and she attended a boarding school on the shores of Lake Geneva—the ideal setting to nurture a deep love for the living world and nature. After finishing high school, a brief stint in nursing studies introduced her to the world of psychiatry, an experience that left a lasting mark. From art therapy to art brut, the transition was seamless. “The repetition of forms, patterns, like in a beehive, intrigues me. It’s meditative,” she says, expressing her love for the obsessive, then listing influences such as Yayoi Kusama, the Facteur Cheval and his naïve palace, Niki de Saint Phalle, and ultimately Jean Dubuffet. It was, in fact, in Dubuffet’s famous Jardin d’Hiver, a protective cocoon with organic forms, that she chose to have her photo taken.

Next came studies at the Beaux-Arts in Lyon, followed by a degree in Material Futures at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London, where she discovered a more open mode of operation, one that resonated more deeply with her novel approach to object design. “I like to let the experimental flow freely in my practice,” admits the young woman, who is not only an artist, but also a designer, and a craftswoman. This overseas program allowed her to develop her thinking, as if the distance from her native Haute-Savoie brought out what had shaped her: that intimate bond with nature and the living world. “It was then that I wanted to celebrate insects. The project From Insects lasted about six months. I set out to push the limits of materials produced by common insects, like bees or the Indian silkworm.” From the resin collected by the former (which bees turn into propolis to seal the hive's tiny gaps), she created a highly resistant, blowable glass, used to craft a series of unique table objects. Using the sericin from the latter—a natural adhesive—she developed a "wooden leather," essentially a leather from insect waste, made of cocoon fibers varnished with bee resin. Layered sheets of this material yield a wood-like substance. Working with the living, by the living, and for the living—this is her mantra.

I set out to push the limits of materials produced by common insects, like bees or the Indian silkworm.

Marlène Huissoud

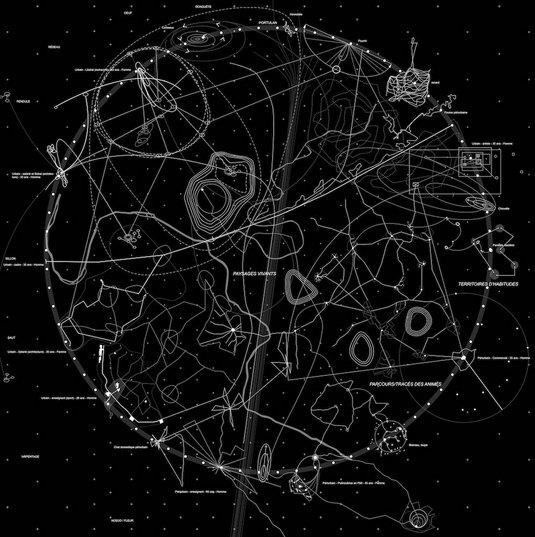

“How can we move from the very small scale of insects to a human scale?” At the heart of her practice and exploration, this question from Marlène Huissoud highlights our ways of creating and producing. Her carefully conceived pieces, which ethically reveal the properties of natural resources, challenge contemporary design methods. Driven by a desire to give insects a presence in the human world—almost as a response to their population collapse—she creates works that insects can inhabit and transform as they please. The Chair (2019) emerged from her collaboration with Robert Francis and Mak Brandon, two scientists at King’s College London, while her primitive hive-work, Beehave, commissioned by the Science Museum Group in London, won her a Wood Award in 2020. This manifesto piece, like her entire body of work, critiques the over-industrialization of beekeeping brought about by the advent of the standardized hive.

What’s the point of creating when we have fewer and fewer resources? Do we really need another chair? My client is the insect. What does it like? What does it need?

Marlène Huissoud

Rather than promoting the industrial applications of her discoveries to major companies, Marlène Huissoud champions the educational dimension of her work—a commitment reflected in her many school workshops aimed at raising awareness of the ecosystem fragility. “My first gesture in the creative process is pedagogy: fostering a different relationship with the living world, showing how insects live.” True to an ecological approach, she creates only a few pieces each year—two or three visually captivating works that blend organic textures with modern forms. With each new project, sometimes in collaboration with scientists, farmers, or beekeepers, the artist questions the legitimacy of the work in terms of its contribution to the living world. “What’s the point of creating when we have fewer and fewer resources? Do we really need another chair? My client is the insect. What does it like? What does it need?” She makes few preliminary sketches before the original piece, only a handful of miniature models, as a kind of memory.

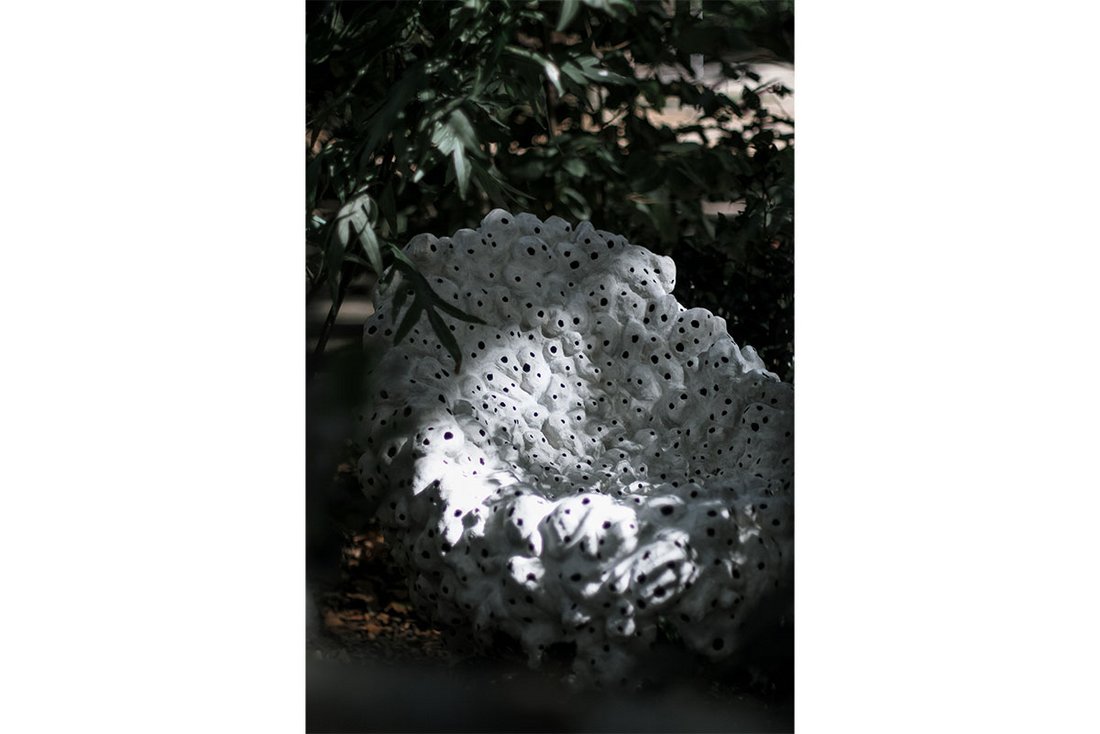

Taking a different approach from biomimicry, Marlène Huissoud’s close observation of insects enables her to go beyond mere imitation. Her recent installation, Mamá, a true sanctuary dedicated to Melipona bees native to the Yucatán Peninsula and revered in Mayan culture, equally involves the artist (the “worker”), fauna, and flora, creating a harmony within the living world. This sacred space, nestled in the heart of the Sfer Ik Museum in Mexico, is in constant transformation with the seasons and, in the artist’s words, invites us to “rethink our coexistence with other species.” It is the bees, and the bees alone, that continually shape the three hundred kilos of cow dung comprising Mamá as they see fit.

Her recent installation, *Mamá*, a true sanctuary dedicated to Melipona bees native to the Yucatán Peninsula and revered in Mayan culture, equally involves the artist (the “worker”), fauna, and flora, creating a harmony within the living world.

Constantly on the move, Marlène Huissoud has decided to leave the noise of the city behind and move back the Alps. She has expressed a desire to publish a small children’s book, naturally about insects, and biodiversity in general. But above all: “I have a monumental project in Haute-Savoie, to create a monument for insects on my family’s farmland, inviting others to collaborate. It’s a lifelong project.” A Garden of Eden, or perhaps a Noah’s Ark… in any case, a true celebration of life that promises the meticulous, enduring effort of an ant at work. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

L'artiste désigneuse Marlène Huissoud dans l'œuvre Le Jardin d'hiver de Jean Dubuffet

Photo © Pierre Malherbet