Marfa, Texas: Art on the Edge of the World

In the silent, comedy film The Gold Rush, a snowstorm sweeps the cabin, where Charlie Chaplin is spending the night, to the edge of a nearby precipice. When he wakes up, he crosses the room to leave but his movement tips the hut dangerously, as the door is already positioned over the void; if he approaches it, he will die. But as he retreats, restoring the balance that was compromised for a moment, he locks himself into a desperate situation. Step by step, his feet move forward and back, feeling the floor tilt on an invisible axis.

The Gold Rush dates from 1925 and just over 60 years later, French philosopher and theologian Michel de Certeau borrowed this scene, featuring the description above, in the opening of an essay titled Pour une nouvelle culture (1968). In this cabin on the edge of the void and the strange dance of its occupants, de Certeau finds an allegory for the hesitation traversing French society in the aftermath of the events of 1968, torn between a conservatism that had become untenable and the uncertainty of a future whose points of reference would bear no resemblance to those of the present. “A shift has occurred. Though we may not be aware of it, a line divides the ‘floor’ beneath our culture, between solid ground and the void; though still intact, it is already on the brink.” An image can travel around the world, from Chaplin’s icy Klondike to de Certeau’s examination of the Latin Quarter in May ’68, and the parable comes back to me here in a state known for its conservative positions, on roads where no snow can be seen, even if the occasional sign reminds us of the possibility (“road may ice in cold weather”), like a provocation thrown out to the desert.

The thread of random memories is sometimes worth following. Is it the cabins that made me think of this scene again? It is true that the houses here sometimes seem to be placed on the ground rather than anchored to it, mobile homes set up in trailer parks, places that have been ghost towns for varying amounts of time—in conversations, I discover that becoming a ghost town is not a permanent state of being (“Terlingua was a ghost town a couple of times”) and that such towns can be resurrected temporarily if, for example, the price of raw materials makes it attractive to exploit the silver mine once again. So homes come and go—but on land divided strictly into squares of private property, which covers 97% of the territory in Texas, leaving only the national parks as commons and lining every road with impenetrable enclosures inside which it would be foolhardy to venture. Thus, we have the paradox of a landscape where the view stretches to infinity but the body collides with it, as if in the strangeness of this meagre depth with inaccessible backgrounds, the country becomes its own diorama.

Is it because of the cliffs, then, that this scene from The Gold Rush came back to me? In fact, the geology here tends to be orthogonal, horizontal with the immense plain underscored by the grid of roads, another horizontal line along the top of the mesas, and between these two parallel planes, the escarpment of the Chisos Mountains and the canyons that run through it, great verticals rising up from the subduction of tectonic plates, halting the gaze—“everyone thinks that a fault is a line, but in reality it’s a surface,” explains our guide Thomas Shaller, geologist and palaeontologist, in a phrase that immediately joins my collection of sentences to ponder. The fact remains that these motifs, the cliffs and the canyons, are just as much an obstacle to what is at play here, and, above all, to understanding the border, which we would be wrong to believe lies clear as an unbroken line, where the Rio Grande plunges between the stone ramparts over near Santa Elena. If a fault is a surface rather than a line, then the border is more of a zone than a mark on a map, with checkpoints scattered over an immense territory, their ramifications stretching far beyond the Rio Grande, and border patrol carrying out differential distribution according to how much they suspect the individuals they stop of being undesirable. As philosopher Étienne Balibar writes in Les Frontières de la démocratie (La Découverte, 1994), “certain borders are no longer located at the borders at all, in the geographico-politico-administrative sense of the term, but elsewhere, wherever selective checks are carried out”.

Living in the folds of a map

There are houses that look as if they are ready to fly away, and there are cliffs whose sheer drops double the horizontal vertigo caused by the desert; but each of these figures is hindered by the combined grip of property and sovereignty, land capital and political control. So why do Chaplin and de Certeau (a strange cabaret duo: Tramp and Jesuit) come to mind here? For two reasons, I think.

On the one hand, the image of a house that is silently tilting (“a shift has occurred, though we may not be aware of it”) is not a bad symbol to indicate the theme of the collective residency project we have created this season, inviting five artists to work together to explore this territory. With the transformations brought about by climate change, a new question has appeared on the agenda of public debate and research, at the intersection between the social and natural sciences: what conditions must be met to ensure that our Earth remains habitable, and what dangers now threaten not the existence of the planet (which has experienced much warmer and colder climates) but its very habitability? This question is being asked today in many places around the world, but to come and ask it in Marfa is to come to a place where, in our imagination, humanity has confronted the uninhabitable—the harshness of the desert—and has decided both to expose itself to it and to resist it. In a sense, this is what Donald Judd’s very gesture could symbolise: on the one hand, to leave our cities and museums, developed and humanised areas, to confront the empty, open space of the plain; on the other, to install works of art in the very heart of this space, which, from hangars with rounded roofs to a hundred boxes in a line, create the space of a possible interiority in the hollow of the desert itself, returning to the very form of the house and bringing it back to its pure expression.

Creating in the midst of the uninhabitable, leaving the house only to bring it back with a single stroke, in the dual guise of shelter and monolith: the artistic gesture is powerful and has had immense posterity, but even more than that, it stands as an invitation to be, in a way, put to the test of the present. Because something in the economy of this confrontation between the inhabitable and uninhabitable, with all the images it conveys of pioneers and new frontiers, is being turned upside down, and I see a sign of this in the way that some of the emblems of this territory now seem to be suspended in the void: when we arrived here (and it’s the nature of travellers to be surprised by the obvious), we discovered a land of cowboys where cows are becoming rare, where the drying up and over-exploitation of farmland are jeopardising the very possibility of extensive livestock farming, while the cowboy hats and longhorns attached to pick-up radiators mark a kind of time-lag between the symbolic and the real.

So we need to look at the question of the world’s habitability in a different way, and remember that the act of creating or building does not alone encompass the possibility of inhabiting a territory: it is also a question of resources, sharing, coexistence, collaboration, competition and management. We also need to reopen and broaden the population count: although the sign at the entrance to Marfa says “pop: 1788”, how can we not add to this number those who arrive and leave, from international visitors for Chinati Weekend, to the people who cross the Rio Grande and pass through the desert and mountains, facing many dangers? And how can we not add the non-human beings that make up the exceptional biodiversity of the Chihuahuan Desert, the local and invasive plants (the buffalo grass that some of us went to weed with the Judd Foundation’s volunteer programme), even the bodies of those who perished in the desert, the traces left by previous human settlements (I’m thinking here of the White Shaman mural on the Pecos River), and a few ghosts that refuse to disappear? The house is tilting, but why, who exactly is living in it, and how can we tally up the numbers and include those who have been left out? Those were the questions that drove us when we arrived—a provisional intuition for an investigation that we obviously couldn’t carry out without first talking to the people who live in this area, the inhabitants of Marfa, whose immense hospitality I would like to acknowledge.

Inhabiting, residing, creating

There’s another reason, though, for thinking about the icy cabin from The Gold Rush amidst the sotol and ocotillo. In the Tramp’s farcical, panicked dance, in the way he rushes to the door and then, realising that his own weight is tilting the house, leaps back, I seem to recognise something relating to the very difficulties of residency. This word ‘residency’ also refers to a house—and the artists and I will have spent several weeks in Marfa occupying houses large and small, watching the sun rise and set from their doorsteps and windows.

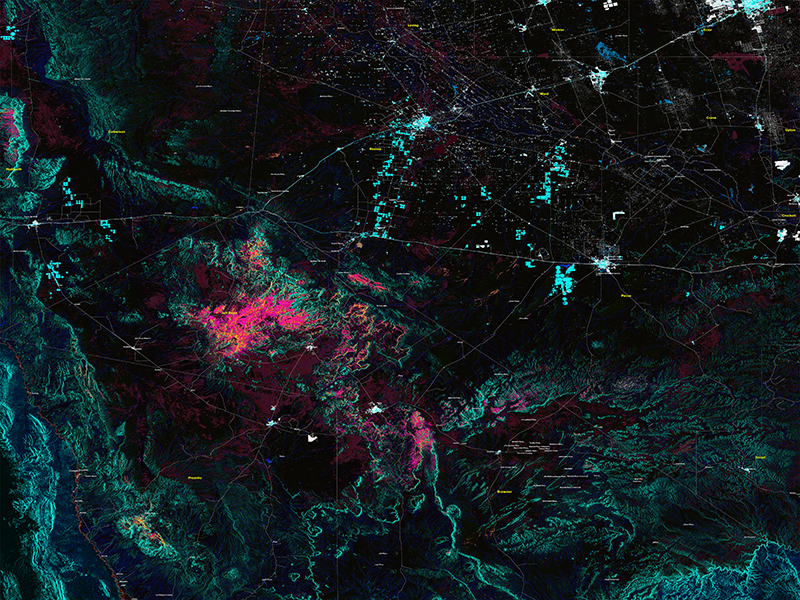

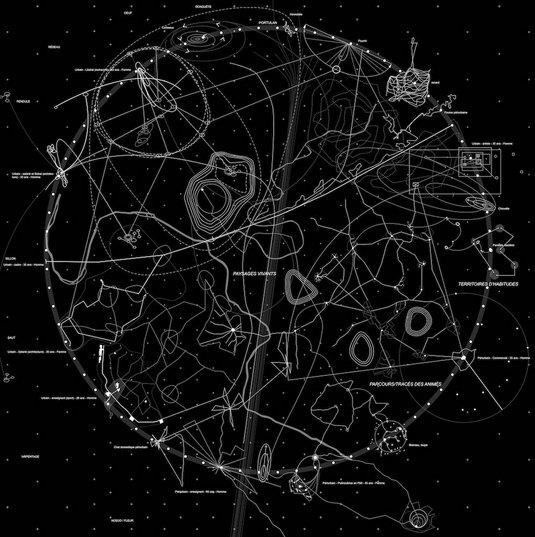

The fact remains that a resident is not an inhabitant, and the very challenge of a residency is to create a bond with the place where you arrive, one that is intense without being intimate—to be there without being from there, neither completely inside nor completely outside. The motif of inhabiting, which was the common thread running through the artists’ projects (in the beautiful diversity of their mediums, from the visual arts to performance, from writing to cartography and podcasting), was doubled by a question posed to artistic creation itself: in this way of connecting a territory to a practice, of wandering through a space in the highly concentrated time of a month-long residency, what are the constraints and limits, and in this exercise, how can we disentangle fruitfulness from discomfort?

These questions are by no means anecdotal: they belong to a range of aesthetic and ethical concerns running through contemporary art, from the dialectic posed by Robert Smithson between site and nonsite in the practice of land art, to current debates on cultural appropriation. What is the relationship between a work of art and the materials it uses? What exactly do artists owe to the people who answer their questions or inspire them, and in what form should they give back to these people when presenting their work at the end of the residency, if ‘restitution’ is not just an obligatory exercise but a guarantee of a certain equity in the exchange? What legitimacy do we have to claim to be speaking from a place where we’ve just arrived and from which we’ll soon be leaving? How do we eliminate, or on the contrary overplay, divert and subvert, the clichés that we carry with us and that prevent us from seeing? Perhaps the strength of a collective residency is that it allows us to mix and mull over these questions together until they become the subject of a shared experience, and to see the range of responses they enable and the makeshift approaches they call for distributed through the projects carried out by each person.

This does not mean, however, that these are, in the words of Michel Foucault (in L’Usage des plaisirs or The Use of Pleasure, 1984), “games with oneself [that] would better be left backstage”, the scruples of artists unconnected with the territory itself: as when the reluctance of interviewees to discuss certain subjects with a resident is directly linked to the criminalisation of abortion, the penalties incurred by those who oppose it, and the calls for denunciation invoked by the law; or when the awareness that we are only there for a short time invites us to seek an appropriate way of translating the experience of those who have crossed the border, while respecting those elements of their ordeal that cannot be shared or appropriated; or when we wonder, as we write, how we can accommodate the diversity of testimonies and take into account, in the tone of a single text, the plurality of statements and voices we have encountered; or when the frustrations experienced in the face of a territory that refuses our approach, in their very violence, the criss-crossing barriers, the bristling barbed wire, the laws that carve out their dominion right on people’s bodies—in all these cases, residents will not be contented with temporarily inhabiting a place, or questioning what is at play in the act of inhabiting it. They will find themselves inhabited, moulded and changed by this very experience, indicating through these intimate movements some of the very real fractures of these places, just as the Tramp running back and forth reveals the pitching of the cabin from which he is trying to escape.

“A line divides the ‘floor’ beneath our culture, between solid ground and the void,” writes Michel de Certeau. In trying to grasp something of the transformations taking place during this residency, as mediums are exchanged between artists and the projects initially imagined change pace and form, in the movement between French and English as each day passes, this dual expression, bilingual and approximate, came to me like a proposition or a password: on the edge/sur les bords. A single-double formula, separated by a slash that acts as a third edge, like a line over which a throng of meanings are exchanged—the multiplicity of les bords challenges the edge’s claim to be a single frontier; in the French bord we hear the American border; in the spatial calculation of limits, on the edge, we hear the imminence of transformations that are already taking shape, on the verge; in the nervousness that can seize you here and leave you edgy, we see the possible transgression of questions we don’t ask or times we let ourselves go too far, borderline questions, borderline jokes; not to mention the way in which the very nature of a residence is to make do with what you find there, to invent with the moyens du bord (the means at hand).

The very nature of what is played out on the edge, on the border, is that it is still undecided: halfway through this residency, I am letting the outer edge of this text fight towards what is yet to come and, here, the final full stop is left dangling — ◼

“Inhabiting the desert”, five artists in residence in Marfa

In collaboration with the Centre Pompidou, Villa Albertine is once again holding its collective and multidisciplinary residency in Marfa, Texas.

Located in the far west of Texas, 60 miles from the US-Mexico border, Marfa’s desert landscape serves as a microcosm in which diverse migration histories and evolving ecological dynamics intersect. In this context, artists and intellectuals can collectively reflect on the ecological and migratory challenges of preserving a habitable world and our relationship with the environments that surround us.

For the 2024 edition, writer Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, journalist Adèle Humbert, architect and cartographer Alice Loumeau, visual artist Josefina Paz and performer Grégoire Schaller have been selected to take part in this residency from 2 October to 2 November 2024.

Related articles

In the calendar

Grégoire Schaller, « No Country for Old Fags », performance, 2024

Photo © Sarah Vasquez