Judith Butler: life as grief, rage and resistance

Continuing its cycle of major intellectual invitations, the Centre Pompidou invites American philosopher Judith Butler to develop an original program throughout the 2023-2024 season, focusing on her work in progress. Conceived in collaboration with the École Normale Supérieure, this invitation will revisit the entire career of this major contributor to international contemporary thought, a figure of queer theory and an attentive and committed observer of the world's political upheavals, in the light of one question: how can we attune ourselves to the experience of mourning and survival that so often runs through our troubled lives today? How can we give shape and impetus to the powers of anger and togetherness that this experience conceals, when it becomes a collective demand for justice? As this series of talks is about to start (the first session will take place on September 14 as part of the Extra! festival, with philosophers Elsa Dorlin and Hourya Bentouhami), a conversation with one of the great voices of the present, for whom living is synonymous with weeping, creating and resisting.

Mathieu Potte-Bonneville — Your book What World is This? A Pandemic Phenomenology, translated in French this autumn, takes the COVID-19 epidemic as its starting point. Do you see this planetary event as an opportunity to analyze the dimensions of the world we live in?

Judith Butler — Covid-19 has, of course, been a pandemic which means that it affected the whole world. Pan-demos: across the world, or across the people of the world. On the one hand, it brought to light a number of stark inequalities. Among those, we can surely include unequal access to decent health care across the world, including vaccines. And even hyper-capitalist countries such as the US, many workers had to choose between going to work to make a living, and provide for dependents, or refusing to work to stay alive, but losing the means to live - the choice is one no one should ever have to make. It was especially poignant to see that workers deemed “essential” (indispensable) were those who were most readily sacrificed, sent to work without proper protective equipment, forced to work in close quarters. We also saw how many people were confined to domestic spaces which were not always sustaining environments: abusive partners, homophobic parents, no access to community, no ability to gather or to grieve the losses borne in the physical company of others. Those who live without permanent shelters were especially vulnerable, and yet in many parts of the world, there is no governmental obligation to make sure that every person is decently housed.

On the other hand, the pandemic did illuminate a global interdependency, an insight of potentially equal vulnerability as living creatures. We had a sense of our bodies as both porous and interdependent. At the same time that social interdependence was something we required it also threatened us with our lives. The pandemic not only generated a reflection on the ambivalent meanings of interdependency, but brought attention to some key socialist ideals: guaranteed national income and equal access to decent health care and housing.

Mathieu Potte-Bonneville — The AIDS epidemic had profoundly disrupted forms of thought and expression, both intellectual and artistic, in stark contrast to the way in which the COVID pandemic almost gives the impression of having been repressed from the collective memory. Do you agree with this observation, and what do you think of this virtual obliteration?

Judith Butler — For many of us, the AIDS epidemic prepared the way for the creation of queer networks, extra-familial communities, that provided services and support during lockdown. Some of the same issues of public mourning and public protest surfaced. Digital art platforms become all the more important, and people with the technology and, often, the ability to subscribe to streaming platforms, became immersed in visual culture. I do agree that the rapid cultural and media movement away from Covid-19 was not just flight from the thought of death, but the ongoing task of mourning. The fact is that people with long COVID are not finished with the pandemic. People who lost loved ones are not finished with COVID, and new waves, though not as strong as previous ones, continue to form and their trajectory remains relatively unpredictable.

My sense was that governments throughout the world wanted their markets to re-open, and so many of the manic declarations about Covid being “over” were ways to deny the loss – and the ongoing task of mourning – and the ongoing difficulty of long COVID which affects so many people around the world. Mania is one dimension of melancholia, the denial of loss; market mania is the intensification of that refusal to grieve or to mark or acknowledge ongoing vulnerability, including physical restrictions and psychic pain. Ideally, the pandemic condition could make us demand equal and adequate medical care, the end to the profound sense of abandonment that so many people feel by both social services and drug companies.

For the French public, your work remains strongly linked to the publication of Gender Trouble, a work that was translated with great delay in France, and which contributed to profoundly disrupting the frameworks of thought and public debate throughout the world. Through this invitation to the Centre Pompidou, we'd like to give the public a better understanding of the trajectory of your work since this essential book. How would you describe the shift between the issues addressed in Gender Trouble and your current research?

Judith Butler — Perhaps it is important to say that Gender Trouble may be the beginning of the French understanding of Judith Butler, but said author had a prior beginning, a training in Hegel and Marx, in the phenomenological tradition, and critical theory. In one sense, the publication was delayed in France, but the US timeline should not set the norm. The timing of translation is an index of what kind of trans-national and trans-linguistic conversation can be had. Sometimes the condition of such conversations is a misunderstanding. For instance, Gender Trouble is not the beginning of gender studies or queer theory. Both were happening before the publication of that work. And yet, from afar, a story can be crafted that has little bearing on reality and, through its circulation, becomes accepted as reality. Gender Trouble never said there were no biological realities, and yet the distorting paraphrase circulates enough that it achieves a “truth-effect.” Nor did Gender Trouble argue that we can choose our genders whimsically. And yet, I finally have no control over that form of reception. At a certain point, one has to distinguish between the authorial understanding and the reception, and allow that disjunction to generate new realities. It is useless to “correct the record”. One has to let the text cancel one’s intentions and follow its own itinerary in the course of translation and reception.

Trouble dans le genre n'a jamais soutenu qu'il n'y avait pas de réalités biologiques, et pourtant la paraphrase déformante circule suffisamment pour produire un "effet de vérité". Trouble dans le genre n'a pas non plus affirmé que nous pouvions choisir nos genres de manière fantaisiste. Et pourtant, je n'ai finalement aucun contrôle sur cette forme de réception.

Judith Butler

My first work on Hegel was concerned with the relation between desire and recognition and, in a sense, that concern continues through much of the work that followed. Of course, politically, especially in the LGBTQIA+ movement, we seek recognition for our desire, but we also have to see that the terms by which any of us are recognized are social and historical in nature. Further, the available schemes of recognition orchestrate the kinds of self-knowledge and self-presentation we pursue. I am interested in how the social world occupies our most intimate relations and passions – interdependency, grief, rage, and resistance. I have tried to pursue different dimensions of this problem of precarity, war, to public mourning, to forms of political resistance, non-violence and to ideals of co-habitation.

If you think about the place that feminist or trans-identity issues occupy today, you're struck by two things: the way these issues are at the heart of contemporary creation, and the way they crystallize violent reactions, almost becoming the central demarcation criterion between progressives and conservatives. How do you understand both this importance and this polarization?

Judith Butler — Transphobia is centrally linked with new forms of fascism and reactionary politics more generally. It is not just an attitude of discrimination, but an effort to strip people of their fundamental rights. Trump tried to make sex assignment inalterable, and both Orban and Putin, in different ways, have identified trans, as well as gay and lesbian rights, as assaults on the nation, even threats to national security. There is a specific phantasmagoric scenario reproduced by contemporary transphobia, resulting in rights-stripping (a key instrument in the fascist arsenal) and in a moralistic justification for sadism. The formula goes something like this: “trans” or “gender” or “gay parenting” (in the case of Meloni) all destruction an established way of life; hence, to defend that way of life (or that fantasy of that way of life), trans must be destroyed. The result is to accelerate and intensify destruction in the name of trying to stop it. We need both to oppose this movement and to understand its nefarious aims and its popular allure. My forthcoming book, Who’s Afraid of Gender? tries to address this.

Transphobia is centrally linked with new forms of fascism and reactionary politics more generally.

Judith Butler

In the work you've done in recent years, the notion of life has taken on an increasingly strategic importance (this was already the case in 2012 in the lecture "What is a good life?" given when you received the Adorno Prize, or in your conversation with Frédéric Worms on the livable and the unlivable). It's this very notion that you've chosen to highlight in the event that the Centre Pompidou will be hosting in April 2024, around you and your guests. To speak of "life" is to refer both to our condition as living beings in its material and physical dimension, and also in its fragility, and to the way in which we can translate it, express it, recount our lives to others and to ourselves; it is to go, ultimately, from the biological to the biographical. Is it this way of linking the order of bodies and that of language that interests you in this concept?

Judith Butler — Of course, it is possible to speak of life, or a way of life, or to ask about what is living in the way that we live. Life has a way of moving between noun, adjective, and verb, and when we speak about what is “living” we can be referring to the bare minimum of staying alive or the most intensive experiences of passion and of art. I would not say that the body has one order and that language has another order. I accept rather that the two are intertwined, and that when we seek to separate the one from the other, we become lost. If we say of one creature that is barely living but of another that it is living fully, we point to an oscillation between modalities of life, and this tells us that life appears in multiple modalities. We have to remain patient with those complications rather than accept severe dualisms that do not serve us, or serve life.

The planetary is surely an important new framework for re-orienting human life in a way that underscores the need for humility and the challenge of reversing destruction and safeguarding the earth.

Judith Butler

The notions of "life" and "the living" are today the focus of much attention from authors who, in the context of the climate crisis and the collapse of biodiversity, want to extend ethical and political attention beyond human beings. Do you see convergences between this use of the notion of life and your own?

Judith Butler — Yes, I have focused perhaps in an anthropocentric way on ethical and social relations, on the fact that my life is implicated in the lives of others, and that certain obligations follow from that. And yet, we have seen how important it is to understand the human creature as a specific kind of animal, and to see that this life, and that the life that is lived in common, depends on living processes that are clearly threatened by climate change and species extinction. The planetary is surely an important new framework for re-orienting human life in a way that underscores the need for humility and the challenge of reversing destruction and safeguarding the earth.

In the course of this season with you at the Centre Pompidou, you'll be joined not only by philosophers and researchers, but also by artists like John Akomfrah, and performers like Maria José Contreras. What echoes do you see between their work and yours, between philosophy and creation?

Judith Butler — In the course of this season with you at the Centre Pompidou, you'll be joined not only by philosophers and researchers, but also by artists like John Akomfrah, and performers like Maria José Contreras. What echoes do yoBoth Akomfrah and Contreras address grief and rage, the problem of building an alliance between the living and the dead, the task of mourning in the midst of political resistance. They also explore forms of art that gather up political losses, documenting what has happened through sensuous media that allow us to feel loss and resistance at once. One activist slogan says, “Don’t grieve! Act!” I take issue with this message, for it is unclear to me whether we can act mindfully and effectively without the capacity to grieve. The loss of that capacity is perhaps the most perilous form of inaction.u see between their work and yours, between philosophy and creation? ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Judith Butler, 2023

© Collier Shorr

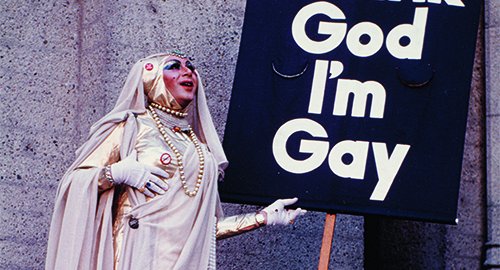

![fierce pussy, Dyke, [1991], photocopy, 43 x 28 cm, Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky © fierce pussy Photo © Centre Pompidou](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/b/csm_dyke-OK_158cd47071.jpg)