Focus on... "Forest Companions" by Takashi Murakami

As a child, Takashi Murakami dreamed of making cartoons. As a teenager, he enrolled in the Tokyo University of the Arts’ painting department, specializing in Nihonga, which means “Japanese painting,” a term that appeared during the Meiji era (1868–1912) when Japan opened up to the West and its cultural productions; the term primarily qualifies works that integrate diverse Western elements into the traditional forms and practices of Japanese art—a reversal of what Europe called “Japonisme,” the craze for Japanese art and design.

As a child, Takashi Murakami dreamed of making cartoons. As a teenager, he enrolled in the Tokyo University of the Arts’ painting department, specializing in Nihonga, which means “Japanese painting,” a term that appeared during the Meiji era.

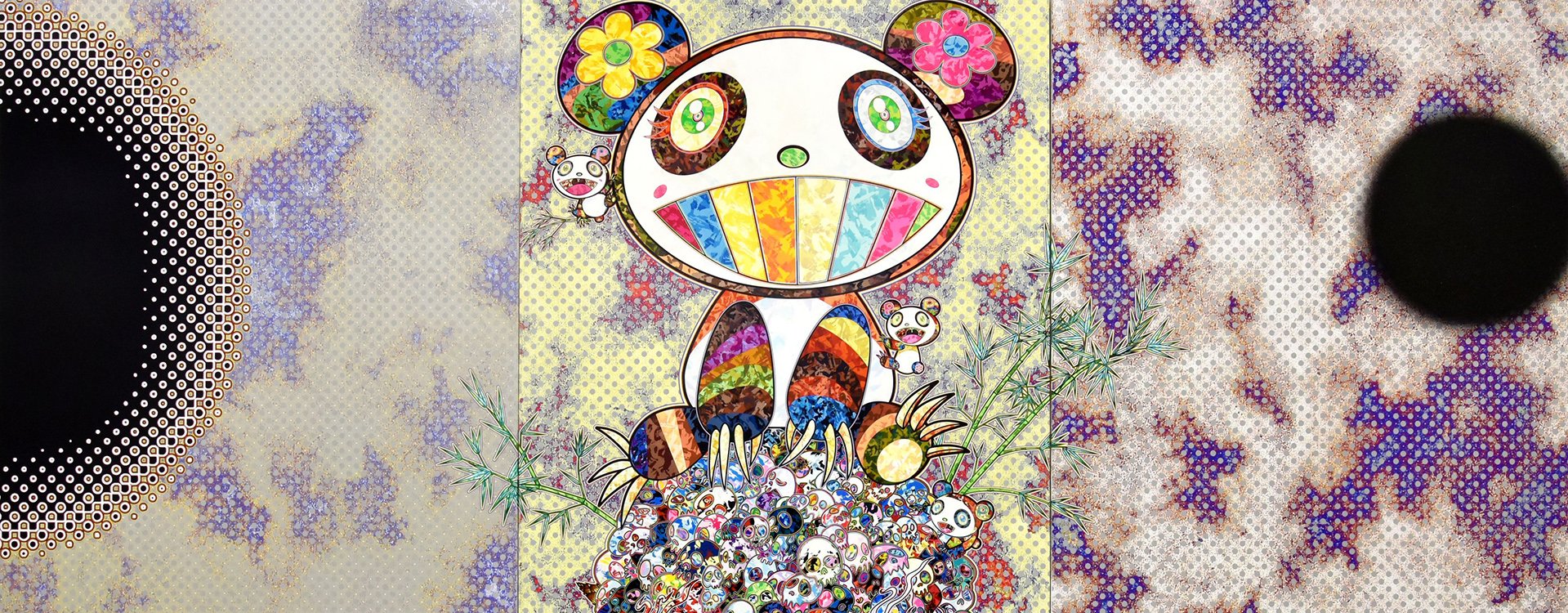

We know from Amaury-Duval’s 1878 memoir L’Atelier d’Ingres, that the painter of La Grande Odalisque displayed a very early admiration for images from Japan, while Théophile Silvestre, wanting readers to feel Ingres’s composite genius in his Histoire des artistes vivants français et étrangers, did not hesitate to describe him as “a Chinese painter lost among the ruins of Athens in the middle of the nineteenth century.” A similar conjunction underscores Murakami’s production, but in a mirror effect, as it were, scored through with the effects of mechanical reproduction and consumer society. His Forest Companions—mini pandas playing with bamboo shoots beneath a multicolored lunatic avatar of DOB (the more-orless monstrous kind of Mickey Mouse that the artist has made his alter ego) perched atop a globe of skulls—is a large-scale demonstration of the mastery, irony, and refinement that Murakami regularly displays.

Mixed into a background of Hollywoodian psychedelics, the work contains the traditionally distinctive features of Japanese art, as summed up by Tsuji Nobuo in History of Art in Japan (2005 for the original Japanese edition, 2019 for the English translation): wondrous adornment (kazari); a sense of playfulness (asobi), always present if only in the background; and animist tropism, wherein each thing is seen as the home of a sacred spirit. Laughter, fear, and enjoyment, all simultaneously and indissolubly woven into a bundle of affects that never quite disconnect from childhood: this is what Murakami works with. It is his version of bijutsi, a vocable also forged during the Meiji era as an equivalent to the Western notion of “fine arts,” and in which a French ear cannot fail to hear bijou (jewel), bathed in its precious and artisanal aura. ◼

* Level 4

Related articles

In the calendar

Takashi Murakami, Forest Companions, 2017

Acrylic on canvas mounted on board 300 × 450 cm | 118 1/8 × 177 3/16 in.

(3 panels)

© 2017 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd.

All Rights Reserved