Beyond Gender: Suzanne Valadon, a Feminist Artist?

Born out of wedlock to a laundress from the Limousin who had migrated to Montmartre, Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938) came from a modest background that did not predispose her to becoming a recognised painter. Traditionally, women artists emerged through family connections, and those who gained access to formal training from the late 18th century onwards were usually from the nobility or bourgeoisie, where artistic practice was considered a pastime rather than a profession. Valadon, however, never attended the prestigious Académie Julian or Colarossi (Grande Chaumière), nor the École des Beaux-Arts (which only admitted women in 1897). Instead, she honed her drawing skills by closely observing the painters for whom she posed—Auguste Renoir, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Jean-Jacques Henner, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, amongst others. Her social background, combined with her strong-willed temperament, paradoxically gave her greater freedom than artists such as Mary Cassatt or Berthe Morisot. Rejecting bourgeois conventions, she had nothing to lose. Already nicknamed the “terrible Maria” as a model, she chose the name Suzanne—given to her by Toulouse-Lautrec in reference to the biblical Susanna, because she posed for elderly men. In taking this name, Valadon symbolically reclaimed her own identity as an artist without disowning her past as a model.

Born out of wedlock to a laundress from the Limousin who had migrated to Montmartre, Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938) came from a modest background that did not predispose her to becoming a recognised painter.

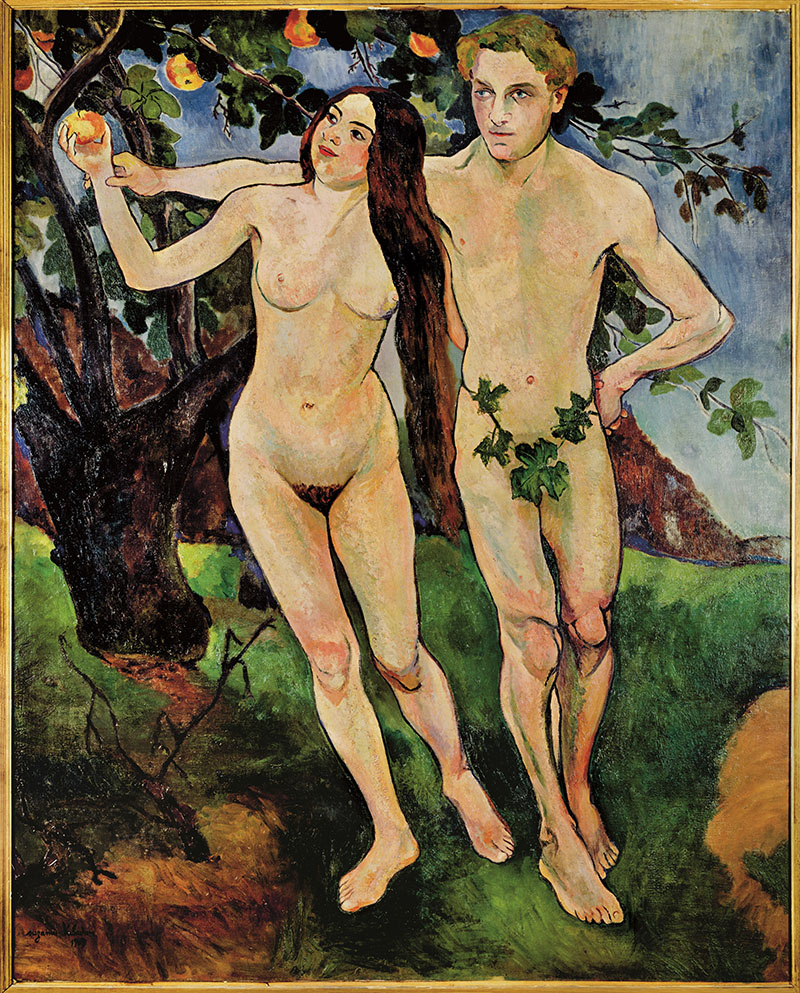

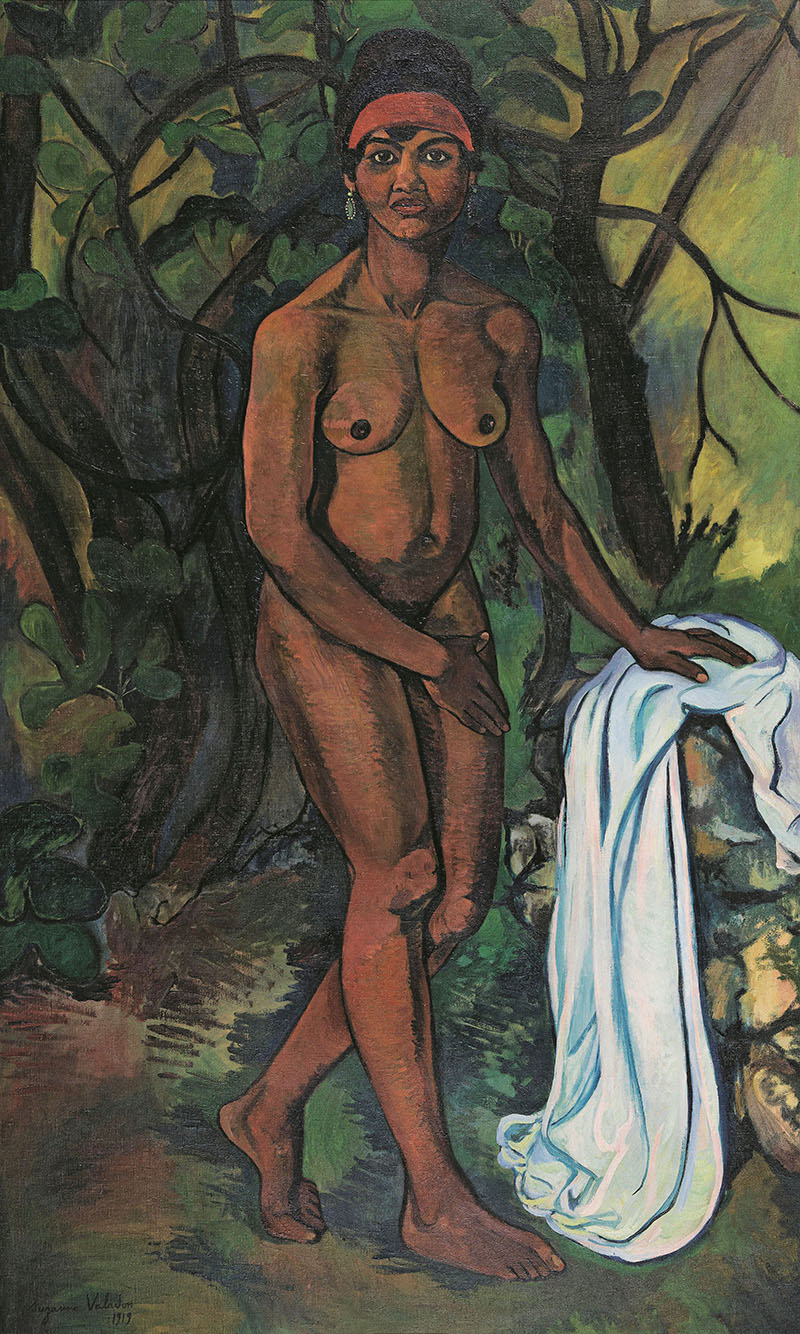

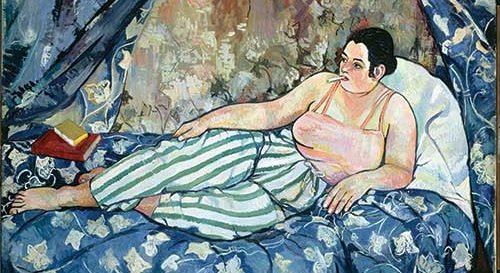

Her trajectory—from passive subject to active artist—mirrors the broader emancipation of women artists at the dawn of the 20th century. Victorine Meurent, Édouard Manet’s model for Olympia (1863, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), struggled to gain recognition as a painter while continuing to pose for others. Juana Romani faced similar challenges. Valadon, however, dismantled such barriers, asserting herself as both muse and creator. She boldly claimed the nude, a genre long denied to women on moral grounds, whether depicting men or women. Her 1909 self-portrait, in which she appears as Eve alongside André Utter as Adam, subverts traditional artist-model dynamics, placing herself at the centre and provoking scandal, particularly due to the age difference between the lovers. She also rejected the idealised female form, dressing her ‘odalisque’ in The Blue Room and portraying herself nude at the age of 59 and again at 66, in 1924 and 1931—without vanity, exposing the aging body of a former model and lover. After Paula Modersohn-Becker in 1906, Valadon paved the way for modern, unflinching female self-portraiture. She famously told Jeanine Warnod: “Never bring me a woman who seeks charm or prettiness—I will disappoint her immediately.” (Yonnick Flot, Lautrec/Valadon: Montmartre Belle Époque, 2019)

Valadon boldly claimed the nude, a genre long denied to women on moral grounds, whether depicting men or women..

Compared to Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Edgar Degas, and recognised early on by Auguste Renoir and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Valadon’s legitimacy in the eyes of critics was often tied to her association with contemporary male masters. However, discussions about her work frequently prioritised her tumultuous life in Montmartre’s bohemian circles—overshadowed by her relationships with mentors, lovers, and her son, Maurice Utrillo—rather than focusing on the distinct visual qualities of her paintings.

Never bring me a woman who seeks charm or prettiness—I will disappoint her immediately.

Suzanne Valadon

A self-taught artist, Valadon in turn introduced Utter and Utrillo to painting, reversing the typical pattern in which women were trained within their father’s or husband’s workshop. In the 19th century, female artists were expected to conform to either a conventionally ‘feminine’ artistic style or, conversely, to adopt a more ‘masculine’ persona. Many resorted to pseudonyms to escape gender bias—Rosa Bonheur, the first woman painter to receive the Légion d’Honneur, sculptor Félicie de Fauveau, and writer George Sand all wore men’s clothing to gain recognition as equals. The archetype of the maudit (cursed) artist remained resolutely masculine in literature. Yet Valadon never explicitly claimed her gender as a defining aspect of her identity, neither as a model nor as a painter: “I have posed not only for women but also for young lads.” Nevertheless, her bold style, marked by vibrant colours, strong outlines, and vigorously modelled figures, earned her a reputation for possessing a “male brutality”. Her independence and lack of formal training were likewise perceived as “absolutely virile”. Even amongst supporters of women artists, gendered interpretations of art remained deeply ingrained. The notoriously misogynistic Degas encouraged Valadon by telling her: “You are one of us!” (June Rose, Suzanne Valadon: Mistress of Montmartre, 1999) A major female artist, it seemed, could only be an exception—either assimilated into the male artistic canon or dismissed altogether. Critics frequently contrasted Valadon’s bold, rough style with the delicate, ethereal work of Marie Laurencin, whom they deemed more “feminine”. Pierre de Colombier even claimed that Valadon appeared to “conceal her gender”, rejecting aesthetic prettiness with her “harsh” painting style (La Revue critique des idées et des livres, 1922).

In the 19th century, female artists were expected to conform to either a conventionally ‘feminine’ artistic style or, conversely, to adopt a more ‘masculine’ persona. Many resorted to pseudonyms to escape gender bias.

Valadon began painting around 1892 and exhibited at the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts from 1894. She never joined the Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs (founded in 1881 to advocate for women’s right to study at the Beaux-Arts). It was only at the age of 68 that she exhibited with the Société des Femmes Artistes Modernes, founded three years earlier in 1930. She left no known feminist declarations and was not politically engaged in the women’s movement. Rather than situating herself within collective action, she pursued an independent artistic path. Yet, despite her lack of explicit feminist claims, Valadon undeniably paved the way for future generations of women artists. Joan Mitchell, for instance, later declared herself “neither woman nor man, neither old nor young” (quoted by Camille Morineau in Artistes femmes, de 1905 à nos jours, 2010). True artistic equality, after all, will only be achieved when artists are seen for their work rather than their gender. ◼

*Texte édité et remanié, extrait du catalogue de l'exposition (éditions du Centre Pompidou).

Related articles

In the calendar

Suzanne Valadon, Catherine nue allongée sur une peau de panthère (1923)

Huile sur toile, 64,6 × 91,8 cm

Lucien Arkas Collection

Photo © Hadiye Cangokce