Barbara Crane, the Eye of the City

Born in 1928, Barbara Crane discovered photography as a teenager, when she would join her father in the darkroom he had set up in the basement of their home. Yet it wasn’t until the mid-1960s, at the age of 36, that Crane produced her first major work, Human Forms—the inaugural series of a monumental body of work marked by experiments, prints, detours, accidents and serendipitous discoveries.

From Chicago to Chicago

Barbara Crane grew up in Winnetka, near Chicago, and attended New Trier High School, where she would later return to pioneer a photography teaching programme. In 1945, she moved to California to study art history at Mills College in Oakland, near San Francisco. At this prestigious women’s college, where photographer Imogen Cunningham once taught, Crane was introduced to the theories of European avant-gardes. The writings of László Moholy-Nagy and György Kepes, two key figures of Chicago’s New Bauhaus—whose legacy she was as yet unaware of—would later have a profound influence on the development of her photographic practice.

After marrying, Crane continued her art history studies at New York University in 1948, equipped with a Kodak Reflex camera gifted by her parents.

After marrying, Crane continued her art history studies at New York University in 1948, equipped with a Kodak Reflex camera gifted by her parents. During this time, she worked as a children’s photographer at the legendary Bloomingdale’s department store on 59th Street. In her spare time, Crane frequented galleries and museums, becoming enthralled by the ancient scrolls at the Met, experimental film programmes at the Guggenheim, and the MoMA’s collections dedicated to Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee. She also developed an interest in the choreography of Ruth St. Denis and José Limón.

However, with the birth of her three children in 1951, 1953 and 1956, Crane temporarily set photography aside. It was only in the early 1960s, after returning to Chicago permanently, that she resumed her photographic practice.

Throughout her life, Barbara Crane repeatedly emphasised how her roles as a woman and a mother influenced her way of conceiving and practicing art. “I grew up in a society where, if a woman was too educated, she would never find a husband. This was something people openly said. Today, it feels like I have a dual personality, a bit like Jekyll and Hyde. I had to behave gently in public, as women were expected to—or at least supposed to. I had to hide much of my motivation as much as possible. You want to be taken seriously, but what would be seen as confidence in a man is perceived as aggressiveness in a woman.”

I grew up in a society where, if a woman was too educated, she would never find a husband. [...] You want to be taken seriously, but what would be seen as confidence in a man is perceived as aggressiveness in a woman.

Barbara Crane

Back in Chicago, Crane resumed her work as a commercial photographer, specialising in portraits for local businesses. One day she met Aaron Siskind, a leading figure of the Chicago School and director of the photography programme at the Institute of Design (ID). Barbara Crane convinced Siskind to admit her to the ID, which she joined in 1964. It was there that Crane finally began to develop an artistic practice, launching a career that would span more than half a century.

Body-to-Body with the City

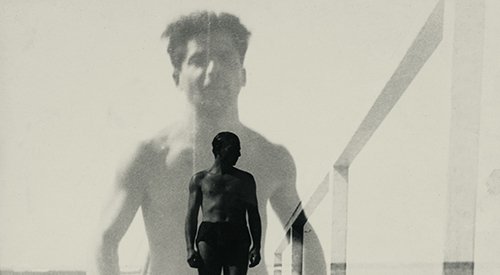

Her early series already hinted at the synthesis of two photographic traditions that would characterise her work in the decades to come: an experimental approach leaning towards abstraction, and a more documentary approach reflecting Crane’s interest in the people around her—their gestures, postures and bonds of affection. In this, she distinguished herself from other ID students. Unable to leave home to photograph Chicago because she had to care for her children, she decided to photograph them instead. For her Human Forms series, she had them pose in front of white or black sheets and overexposed the negatives to create a striking graphic effect, reducing these anonymous bodies to delicate lines on the verge of abstraction. Her children, tough negotiators, demanded 35 cents an hour and insisted their faces not appear in the images; Crane complied, producing what became her first photographic series, quickly noted for its formal originality.

For her Human Forms series, she had her children pose in front of white or black sheets and overexposed the negatives to create a striking graphic effect, reducing these anonymous bodies to delicate lines on the verge of abstraction.

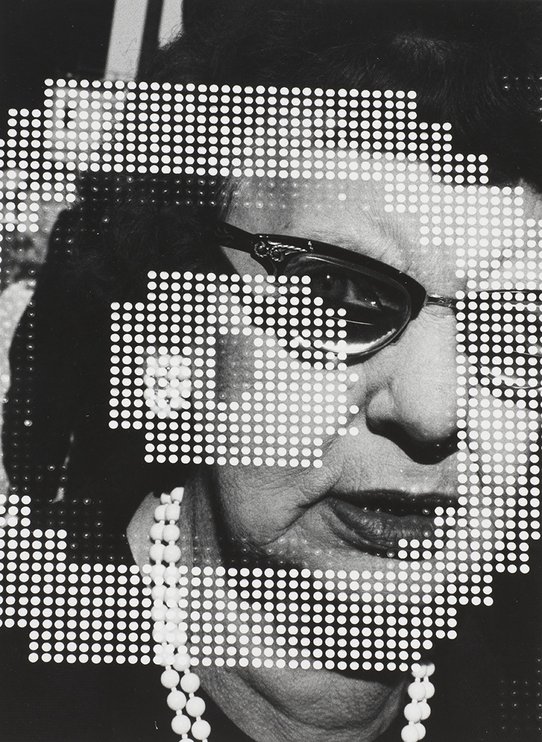

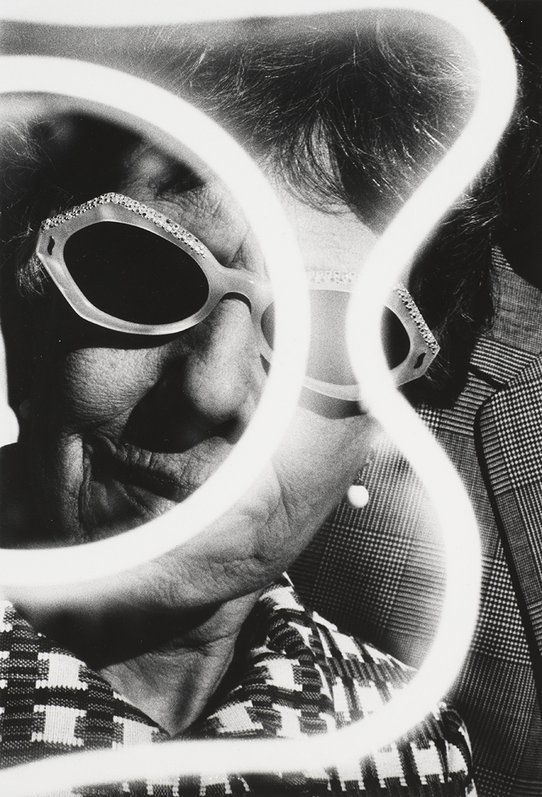

The Institute of Design’s encouragement of experimentation led Crane to develop new photographic methods and processes. By the late 1960s, she began experimenting with Polaroid techniques, creating double-exposed portraits of Chicago residents exiting the Carson Pirie Scott department store, interwoven with neon lights and other luminous city motifs. These hallucinatory portraits, titled Neon Series (1969), brought Crane increasing recognition and invitations to participate in group exhibitions.

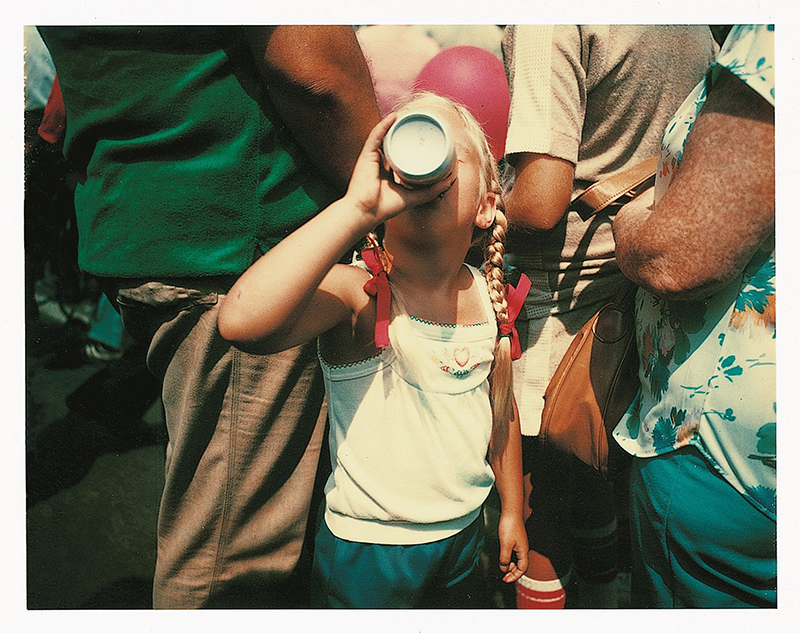

Soon, Crane sought to immerse herself in the life of Chicago’s residents. Observing the flow of passersby at the entrance to the city’s Museum of Science and Industry, she created a titanic, cinema-inspired series. People of the North Portal (1970–71), which she described as a vast “human comedy”, comprises over 2,000 photographs, part of which entered the Musée National d’Art Moderne’s collection in 2023. Following this, in 1972, Crane embarked on a photographic project that would occupy her for several years. Stepping away from the monumental buildings of the business district—the Loop—she turned her lens to the exuberance of Chicago’s population in the city’s parks and beaches. Here, she displayed a keen sensitivity to the choreography of bodies and the sense of complicity emerging from the interactions she observed.

Reinventing her Practice through Commercial Commissions

From her first teaching position in 1964 at her alma mater, Winnetka High School, to her appointment as Professor Emerita of Photography upon her retirement from the prestigious School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1995, Barbara Crane earned a reputation as an outstanding teacher. Many of her students fondly remembered her, as evidenced by the tribute paid to her by writer Philippe de Jonckheere in the exhibition catalogue. Alongside her teaching career, Crane skillfully leveraged commercial commissions in the 1970s to renew her photographic practice.

Amongst these, the large-scale mural she created in 1976 for the Chicago Bank of Commerce stands out as a remarkable example of her ever-evolving practice. Titled Chicago Epic, this work, originally nearly seven metres long (and presented in the exhibition in a reduced monumental format), amalgamates recurring motifs from Crane’s oeuvre. The ceaseless flow of passersby, Chicago’s modernist architecture, advertising signs, pigeons taking flight, and even a subtly integrated self-portrait coexist in the “controlled chaos” of this composition, emblematic of Crane’s formal radicalism.

At the same time, the photographer accepted commissions from other companies and institutions. Although they provided a modest income, these projects allowed Crane to experiment with new forms. For a series created for Baxter Travenol laboratories, she offered a highly personal interpretation of her contact sheets, playing with inversions and surprising arrangements in the darkroom. Far from dismissing these commercial assignments, Crane viewed them as opportunities to step outside her comfort zone, using their constraints to push her work in increasingly radical directions.

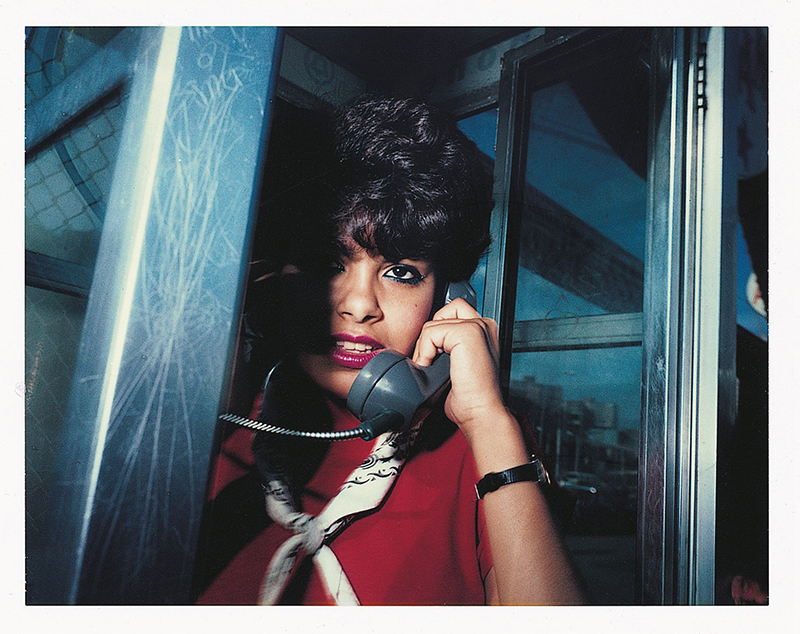

Barbara Crane and the Polaroid

The final section of the exhibition highlights a new direction in Barbara Crane’s practice at the turn of the 1980s. During this period, Crane temporarily relocated to Tucson, Arizona, to prepare for the first major retrospective of her work at the Center for Creative Photography in 1981. Without access to her darkroom, she benefited from an agreement with Polaroid’s Artist Support Program, which provided her with materials in exchange for prints. As she recounted to her French gallerist Françoise Paviot, Crane turned necessity into an opportunity to explore the distinctive chromatic ranges of Polaroid film: “In the 1970s, I lived in an environment conducive to color photography: the sky was blue, people wore brightly colored clothes, and everything was bathed in a warm, sunny atmosphere. It was during this period that I began shooting in color […]. My use of color was a response to my experience of the place, the landscape, and its people. But perhaps my real engagement with color photography came with Polaroid, which had a completely different color quality compared to other films. Polaroid also fulfilled my need to see immediately what I had done so I could move forward and explore something else.”

In the 1970s, I lived in an environment conducive to color photography: the sky was blue, people wore brightly colored clothes, and everything was bathed in a warm, sunny atmosphere. It was during this period that I began shooting in color.

Barbara Crane

Polaroid and colour film marked a turning point in Crane’s work. With her camera in hand, she took advantage of its compact size to blend into crowds at festivals. Day and night, she approached people closely, capturing their affectionate and playful gestures in compositions often characterised by surprising framing.

For Crane, the Polaroid was also a tool for exploring the uncanny. This is evident in her On the Fence series (1979–80), with its mysterious, decontextualised objects placed on a grid and photographed head-on, as well as in her Monster Series (1982–83), unsettling images of Chicago’s dry docks where ships are repaired. These works reveal a surrealist spirit that emerged in her photography during the 1980s.

From the rigour of the darkroom to the spontaneity of Polaroid, from Chicago’s beaches and buildings to the desert’s imaginary landscapes, Barbara Crane’s work draws its power from the tensions running through it, as well as from the absence of boundaries she imposed on herself. Often associated with the Chicago School and its eminent members—Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind and Ray K. Metzker—Barbara Crane pursued a deeply personal path. Her work reflects an insatiable desire to experiment in all directions while remaining in fruitful dialogue with her peers. ◼

Related articles

In the calendar

Barbara Crane, Beaches and Parks, 1972-1978 (détail)

Collection Barbara B. Crane Trust © Barbara B. Crane Trust

© Centre Pompidou