The Day Pierre Boulez conducted the Music of Rockstar Frank Zappa

J

anuary 9, 1984, Paris, Théâtre de la Ville. The final notes of the programme “An American Concert” are still hanging in the air as Pierre Boulez casts a glance towards the wings. Frank Zappa refuses to come out and take a bow—not because the audience response is too tepid for his taste, but simply because he’s devastated. The American rockstar had placed so much hope in this moment that he’s struggling to swallow his disappointment.

Seven years earlier, Zappa had approached Pierre Boulez with the idea of performing his compositions—pieces he would later rework for the thirty-one musicians of the Ensemble Intercontemporain. He chose Boulez precisely for his famed rhythmic precision. He was, as Zappa said, “the right guy”. But perhaps the acoustics of the hall were too dry, or the rehearsal time too limited for everything to unfold with exacting clarity. Boulez senses Zappa’s dismay. He walks towards him, warmly invites him to join the musicians on stage and acknowledge the audience. Zappa is tense. The applause is polite. Curtain.

“Two enfants terribles united”

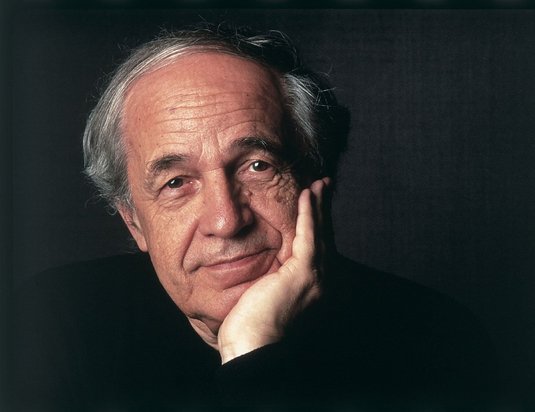

“Pierre wasn’t entirely comfortable, and neither were we,” recalls flutist Sophie Cherrier, who was present that evening. The photographs of the two men tell the story: bodies slightly apart, stiff expressions, restrained smiles. Boulez is dressed in a three-piece suit with a vest subtly edged in white and a tie. Zappa, a head taller, wears an oversized double-breasted jacket, his signature long hair and thick mustache giving him the look of a rock eccentric. Two styles, two worlds. Art music versus popular music.

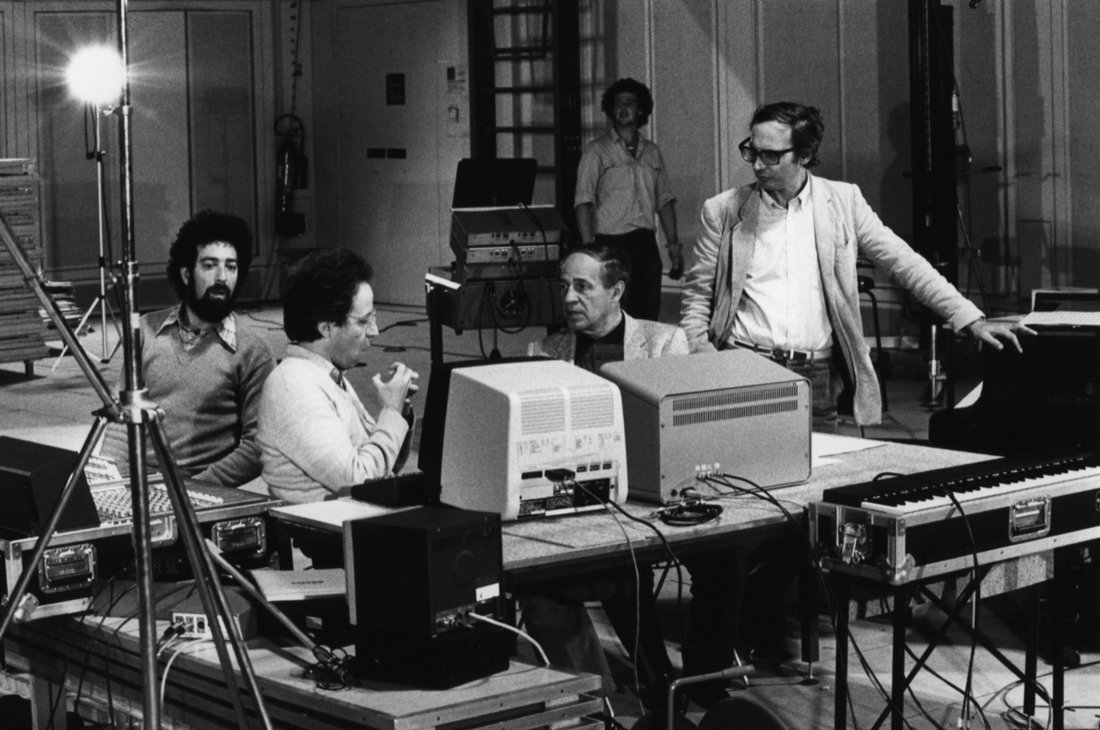

“Two enfants terribles united,” declared The Washington Post, reviewing Boulez Conducts Zappa: The Perfect Stranger, the album recorded at Ircam between January and April 1984, and released later that summer.

Boulez is dressed in a three-piece suit with a vest subtly edged in white and a tie. Zappa, a head taller, wears an oversized double-breasted jacket, his signature long hair and thick mustache giving him the look of a rock eccentric.

The reception in Paris was tinged with misunderstanding. Was Boulez trying to provoke? Known as one of the most exacting figures in musical history (Richard Wagner, Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern …), Boulez had also taken on a musical monument: Wagner’s Ring Cycle at Bayreuth, staged by Patrice Chéreau for the centenary of the work. While the 1976 premiere was met with boos, “the curtain calls lasted an hour and a half in 1980, still with Chéreau,” recalls Laurent Bayle, former director of Ircam (Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music) and the Philharmonie, and general curator of “2025 année Boulez” (Boulez would have turned 100 this year).

That night in January 1984, critics were unaware that the two musicians shared a passion for Edgard Varèse and Igor Stravinsky, or that Zappa had begun writing classical music at age fourteen—long before his rock career took off. Among the performers onstage that evening, however, recognition came quickly.

“As soon as rehearsals began, I realized we were dealing with a great composer,” recalled horn player Jacques Deleplanque in a 2018 interview with the magazine Citizen Jazz. “His pieces were top-tier contemporary music—fully conceived and written. He was incredibly demanding, meticulous—almost worse than Boulez. He left no room for improvisation. Every nuance, every accent was calculated. It was fascinating. [...] Boulez had analyzed and understood the works [The Perfect Stranger, Dupree’s Paradise, and Naval Aviation albums]. He had his own vision of what Zappa’s music should be. He even wanted to adjust some of the tempos—but to no avail.” This, from a conductor who had always granted performers a degree of interpretive freedom

That night in January 1984, critics were unaware that the two musicians shared a passion for Edgard Varèse and Igor Stravinsky, or that Zappa had begun writing classical music at age fourteen—long before his rock career took off.

From the 1960s and 1970s onwards, Pierre Boulez gained international recognition as a conductor. He was quickly invited to lead prestigious ensembles, such as the Cleveland Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and the New York Philharmonic.

In 1966, outraged that André Malraux had appointed Marcel Landowski as Directeur de la musique instead of him—a representative of a more progressive vision—Boulez turned his back on France, a decision that would later be held against him when he returned to establish Ircam at the request of President Georges Pompidou (prompting the publication of his article “Why I Say No to Malraux” in Le Nouvel Observateur).

Boulez also held bitter memories of the backlash he faced after signing the so-called “Manifesto of the 121” in 1960, opposing the Algerian War. He would never again publicly engage in political debate.

His collaboration with Zappa reflects the deep respect Boulez held for any composer he deemed serious and professional, even if their artistic world differed radically from his own. “I’m interested in the intrusion of different instrumental styles and musical practices that lie outside the ‘classical’ domain,” he shared in the pages of Libération in 1984. “Bringing these practices together strikes me as entirely captivating. But the condition I set for such collaboration is that all parties involved must be professionals. I have no interest in vague, feel-good ecumenical encounters.”

Inventing a new language

Above all else, what drove Pierre Boulez was the desire to innovate—to invent a new musical language. Early on, this impulse took shape through his engagement with the twelve-tone techniques of the Second Viennese School and with electronic music. From his first compositions in 1945—Variations for the Left Hand and a Quartet for Four Ondes Martenot—he consistently intertwined music with literature (René Char, Stéphane Mallarmé, Antonin Artaud), theatre (he served as music director for the Renaud-Barrault Company), dance (Bluebeard’s Castle with Pina Bausch), visual art (Paul Klee), and architecture (the Bauhaus movement).

Yet, “he wasn’t particularly interested in cinema or jazz”, recalls Andrew Gerzso, former director of pedagogy and cultural outreach at Ircam, who joined the institute at its inception in 1977. “He saw electronics as a space in which he could create a new kind of musical writing. There was no strict separation between the electronic and the instrumental components—they had to merge!”

“Pierre would sometimes give me instructions through metaphor. When we were working on Répons, for example, he said: ‘In this section, I imagine a transformation like a drop of oil falling into a puddle of oil.’ At other times, the instructions were more precise.”

Pierre Boulez saw electronics as a space in which he could create a new kind of musical writing. There was no strict separation between the electronic and the instrumental components—they had to merge!

Andrew Gerzso, former director of pedagogy and cultural outreach at Ircam

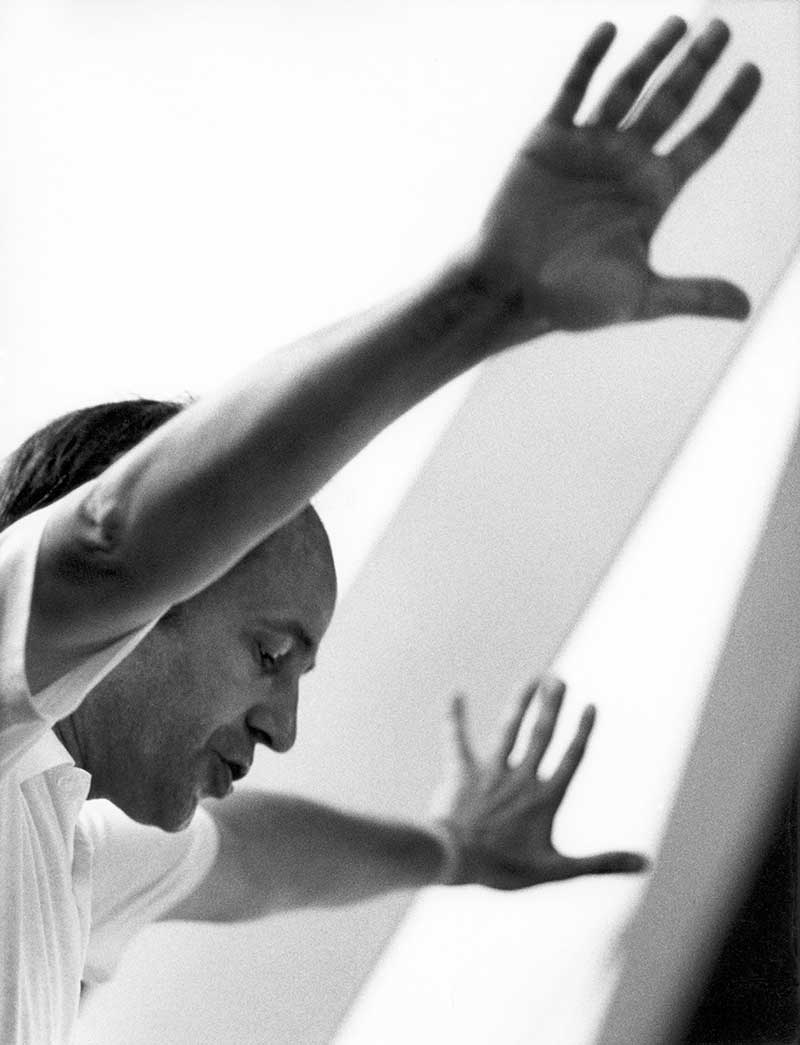

Pierre Boulez became a conductor almost by necessity—driven by the rhythmic complexity of his own compositions, which few others could interpret accurately. Entirely self-taught, he developed a new, batonless conducting technique, immediately legible to performers. As flutist Sophie Cherrier, who joined the Ensemble Intercontemporain in 1979, explains: “It was the clearest, simplest, and most direct conducting I’ve ever experienced. Everything came through his hand. He even said that he was playing the piece with his hands.”

Transmission was one of Boulez’s guiding principles. This was evident in his teaching at the Collège de France (from 1977 to 1995) and in the creation of the Lucerne Festival Academy in 2004. His approach to teaching was never dogmatic but always precise, deeply attentive to others, and marked by extraordinary patience. Olivier Mille’s 1989 documentary Pierre Boulez: Naissance d’un geste (Birth of a Gesture) offers an illuminating portrait. We see a relaxed man, combining a quiet humour with rigorous musical insight.

“Pierre gave us his absolute best, so it was only natural for us to give our best in return,” says violinist Kang Hae Sun, to whom Boulez entrusted the performance of Anthèmes 2. Sophie Cherrier recalls a rare emotional moment: “I once saw Pierre Boulez with a tear in his eye while conducting Schoenberg’s Gurre-Lieder. He always conducted with restraint, but before turning around, he quickly wiped his eyes. So let’s stop saying he didn’t have feelings! He felt and lived the music profoundly.”

A self-taught conductor

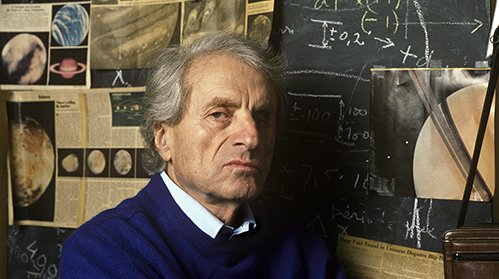

Pierre Boulez was born on March 26, 1925, in Montbrison (Loire), to a Catholic father who was an engineer and a more unconventional mother. He began piano lessons at the age of six, but initially set his sights on becoming an engineer. Having earned his baccalauréat at sixteen (in 1941), he went to Lyon to prepare for the entrance exam to the École Polytechnique through advanced mathematics. But it was not his path. Instead, he entered the Paris Conservatoire to study harmony—though he failed the piano entrance exam.

Encouraged by Olivier Messiaen and René Leibowitz in his harmony studies, he later travelled with the Renaud-Barrault theatre company, where he served as music director.

In New York, Boulez met John Cage, Igor Stravinsky, Edgard Varèse, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and others—encounters that strengthened his conviction to break away from ossified academicism. This stance would give rise to some of the sharp phrases that became part of his legend, most famously, his 1967 declaration in Der Spiegel: “We must burn down the opera houses.”

For Laurent Bayle, such a statement was Boulez’s way of criticizing institutions that endlessly repeated the same works under amateurish conditions, and a call to reimagine them entirely. “In reality, Boulez wasn’t rejecting the past,” Bayle explains, “but advocating for the freedom to choose one’s sources from the musical heritage and to pursue one’s own musical language.” In this sense, Boulez placed himself within a continuum—never seeking to wipe the slate clean. Bayle continues: “He didn’t stand for a total rejection of the past or for a grand revolutionary break, but for the essential renovation of tradition, the need to sift through it and retain only what allows us to move forward. He was more of a progressive than a radical.”

Boulez' greatest strength wasn’t utopia, but his ability to shorten the gap between idea and implementation. He was a pragmatist who, through persistence, managed to turn ideas into reality.

Frank Madlener, director of Ircam

A builder-musician

The composer of Le Marteau sans maître, Pli selon pli, Répons, Visage nuptial, and Notations was also a builder, of both an avant-garde body of work (which has since become part of the contemporary canon) and of institutions. His music was rooted in contemporaneity and remained open-ended—he would change tempos, extend or revisit pieces, as with Incises and Sur Incises.

Boulez also built institutions that he helped bring to life: Ircam (the first to bring together musicians, researchers, and engineers working collaboratively, inaugurated in 1977 alongside the Centre Pompidou, with which it is affiliated), the Opéra Bastille, the Cité de la Musique at La Villette, and the Philharmonie de Paris.

“His greatest strength wasn’t utopia,” says Frank Madlener, current director of Ircam, “but his ability to shorten the gap between idea and implementation. He was a pragmatist who, through persistence, managed to turn ideas into reality.”

It is difficult to grasp just how fierce the battles once were, as Laurent Bayle reminds us. “After the creation of Ircam, the situation evolved and grew increasingly complex, to the point that in 1979, Françoise Xenakis (wife of composer Iannis Xenakis), then editor-in-chief of the culture section at Le Matin de Paris—a socialist newspaper—wrote a multi-page article declaring: “if the Left wins in 1981, Ircam must be shut down!”

Today, the institution remains very much alive—an heir to the spirit of the musician who passed away in 2016, without being bound by it. “Pierre Boulez had only one directive, one we heard more than once: ‘Create, act—above all, do not replicate’,” concludes Frank Madlener. ◼

Related articles

Pierre Boulez and Frank Zappa in the recording studios at Ircam, 1984

Photo © Patrick Aventurier Gamma/Rapho via Getty Images