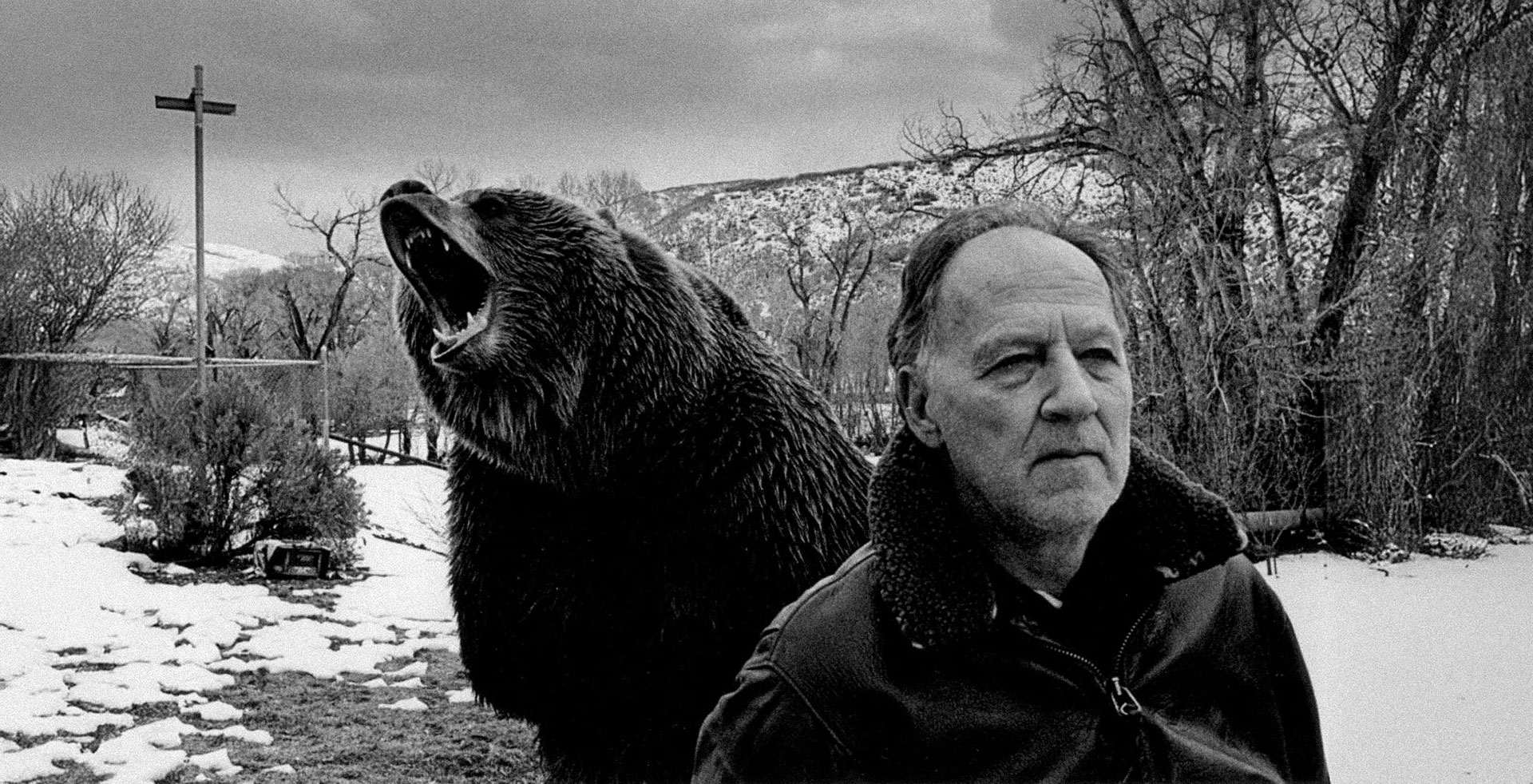

Werner Herzog, le réalisateur qui risque sa peau

More present than ever in theaters, documentaries owe their resurgence on the big screen to the incredible flexibility of their current forms, the freedom of their creators, and the curiosity of their audiences and exhibitors. The realm of cinéma du réel now stretches endlessly. From the depths of intimacy to the digital waters of installation art, there is no longer any question of setting aside a particular documentary gesture as obsolete. Only, perhaps, the term cinéma-vérité has been definitively abandoned, as it was early on by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin, who introduced it to France. Cinéma-vérité was immediately off-putting to Werner Herzog, who denounced its claim to “a superficial truth, a truth of accountants.” For Herzog, cinema is above all the domain of secrets: secrets locked in the body of a former feral child (The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, 1974) or the incomprehensible babble of Pennsylvania cattle auctioneers as they chant their bids (How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck, 1976). Preserving these secrets, for Herzog, means refusing to force confessions from his subjects at any cost. Thus, in Grizzly Man (2005), Herzog steps into the frame, exposing himself to the audience as he listens through headphones to the recording of Tim Treadwell’s death, captured at the exact moment the bear killed him. Yet Herzog does not allow the viewer to hear this ultimate, obscene reality.

Cinéma-vérité was immediately off-putting to Werner Herzog, who denounced its claim to “a superficial truth, a truth of accountants.”

From the legacy of the 1960s—synchronous sound, lightweight cameras, and long takes—today’s documentary has drawn deeply. The technique of synchronous sound is now firmly established, and “direct cinema” has become a model for high-end television. What, then, can cinéma du réel aspire to in 2009? What might it gain by engaging more closely with fiction, instead of patrolling its boundaries like a guard dog? “Isn’t our notion of reality today as poor, lifeless, and reduced as a taxidermied wild boar?” recently asked Claudio Pazienza, the director of Scenes de chasse au sanglier. Carcass or fresh meat? By picking freely from wherever it chooses, the documentary genre might save its skin—on one condition: that it risks it.

A tireless traveler to the ends of the earth (Encounters at the End of the World, 2007) and even its peripheries (The Wild Blue Yonder, 2005), Werner Herzog always takes risks and has moved freely since 1970 between documentary and fiction. Sometimes he extends one into the other, as when he sharpened his perspective for Kaspar Hauser through Handicapped Future and Land of Silence and Darkness (1971), or when he wrote Rescue Dawn (2006) based on Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1997), his documentary about a pilot taken prisoner in Vietnam. At other times, he returns to the craft of acting, as in My Best Fiend (1999), a tribute to his friend Klaus Kinski, whom he directed in Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Woyzeck (1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982), Nosferatu (1979), and Cobra Verde (1987). And at other times, he pushes the fictional possibilities of science to their limits in the “documentary fantasies” such as Lessons of Darkness (1992) and The Wild Blue Yonder (2005).

Herzog’s most baroque, extravagant fictions, and his most modest documentaries converge around a single obsession: his fascination with the extraordinary.

Herzog’s most baroque, extravagant fictions (Fitzcarraldo, with its 400 extras and a 360-ton boat hauled over Peruvian mountains) and his most modest documentaries converge around a single obsession: his fascination with the extraordinary. Surviving in extreme conditions, as Herzog himself did by walking from Paris to Munich in the winter of 1974, unites figures as disparate as a person with disabilities, an athlete, a scientist, and a conquistador. Whether trial or ecstasy, the filmed exploit enables access to the subject’s inner truth. This might serve as a definition for all documentary endeavors, except that Herzog chooses subjects whose “interior” is already projected outward: Fini Straubinger, the deaf-blind protagonist of Land of Silence and Darkness (1971), who translates hearing and speech into the palm of her hand through tactile signing, or the carpenter and ski jumper of The Great Ecstasy of the Woodcarver Steiner (1974), who literally launches himself into the air, never certain whether his rapture will end in death.

Ski jumping, that extreme Bavarian sport, serves as a metaphor for the stakes of filmmaking according to Herzog. Each shoot combines an insane faith with impeccable technical mastery.

Ski jumping, that extreme Bavarian sport, serves as a metaphor for the stakes of filmmaking according to Herzog. Each shoot combines an insane faith with impeccable technical mastery. Like Steiner, whose performances forced ski jump organizers to move safety barriers, Herzog pushes the boundary between documentary and fiction, as well as between the film and its remake (Nosferatu recreates certain shots from Murnau’s eponymous film) and between the filmable and the invisible (the hypnosis of actors lending an atmosphere of trance to Heart of Glass, 1976).

The new territories of the documentary are charted through a double journey: horizontal (filming across five continents) and vertical (mountains and skies, volcanic depths, oceans, and the body’s interiors). Herzog titled one of his works Fata Morgana (1970), after the snow mirages that make distances and boundaries indistinct. ◼