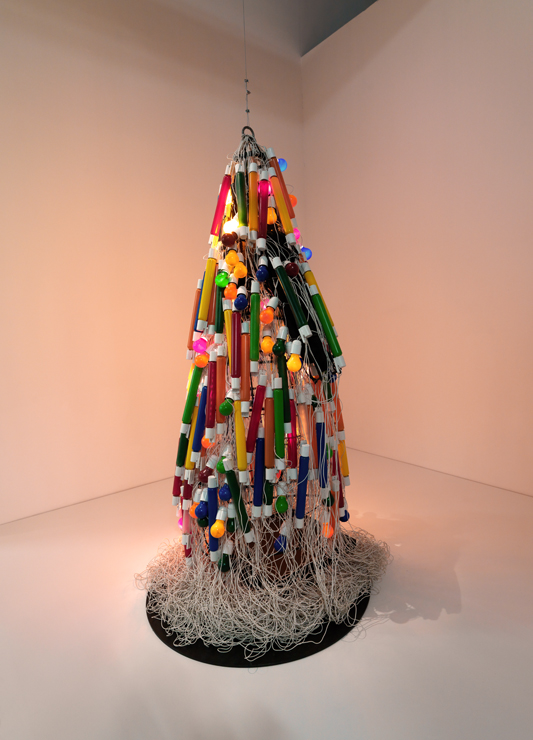

Focus on... "Denkifuku", Atsuko Tanaka's Electric Dress

The 1950s in Japan were characterised by massive Americanisation and exceptional growth in consumption, driven by the Korean War, which transformed the archipelago into a supply base for American forces. This period also saw the rise of a mass leisure culture, symbolised by an electric game, pachinko, a hybrid between a pinball machine and a slot machine, which became extremely popular. In 1953, the electrification of household appliances accelerated, and by 1955, televisions began to make their way into homes, making the "electric fairy" an omnipresent part of everyday Japanese life.

It was in this context that Atsuko Tanaka (1932–2005) created the Electric Dress, a work that would become emblematic of her career. Tanaka was a key figure of the avant-garde Gutai movement, which she joined in 1955 at the invitation of its founder, artist Jirō Yoshihara (1905–1972). Gutai, heralding a renewal in Japanese art, placed a strong emphasis on experimentation with materials and performance. Tanaka, one of the few women in the group, made a significant impact with groundbreaking works such as Work (Bell), a sound installation using ringing bells first exhibited at Gutai’s inaugural exhibition, and Work (1955), an outdoor installation combining colourful fabrics and interaction with the environment, later recreated at Documenta 12 in Kassel in 2007.

In 1956, at just 24 years old, her Denkifuku (“Electric Dress”), inspired by Osaka’s neon signs, earned her international acclaim. Despite the risks, Tanaka wore the dress herself during a happening at Gutai’s second exhibition. The garment, weighing about 50 kilograms, featured 200 glowing bulbs in nine colours. This fusion of art, technology, and daily life functioned as both an artistic object and a performance piece. Tanaka’s work epitomised the group’s motto: “Do not copy others.” She became the first artist to centre herself in an electrically powered apparatus, cementing her place as a pioneer of body art.

She became the first artist to centre herself in an electrically powered apparatus, cementing her place as a pioneer of body art.

By donning the Electric Dress like a second skin, Tanaka spotlighted the relationship between the female body and its external covering, foreshadowing the civil rights movements and feminist discourses of the 1960s. In later years, other female artists, such as Marina Abramović (b. 1946), Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019), Valie Export (b. 1940), and Sophie Calle (b. 1953), would also turn to performance art to challenge taboos and patriarchal stereotypes.

It was an exhilarating moment. I exalted myself.

Atsuko Tanaka

Today, the Electric Dress is part of the Centre Pompidou's collection. Reconstructed according to Tanaka’s instructions for the major Gutai retrospective at the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume in 1999, it was showcased in the 2009 "elles@centrepompidou" exhibition, highlighting female artists in the museum's collection. This luminous sculpture is still frequently displayed at the museum. Its hypnotic play of lights underscores the importance of this piece in Tanaka’s oeuvre: “It was an exhilarating moment. I exalted myself”, she once reflected. ◼